Artifacts of order and disorder

—

Lists have become all the rage in social media circuits over the past couple of years, so much so that I might have titled this entry something like ‘5 artifacts of order and disorder (you won’t believe #3!)’. What I present here, though, is not so much a list but rather a small constellation of cultural artifacts I’ve gathered while mulling over contemporary Euro-American ideas about stuff – ideas about material order and disorder; about what constitutes appropriate and ethical accumulation, consumption, and divestment; about the ‘proper’ arrangement of domestic space and the clutter that always seems to pose a threat; and about the kind of care we should and shouldn’t show toward our objects. In all of this, I’ve become particularly interested in how ideas about stuff have worked their way into popular and professional discourses relating to questions of mental health and illness during the past twenty or so years. The shape that emerges from this constellation, which I am only just beginning to apprehend, speaks volumes about late-capitalist transformations of subjectivity and normative personhood (not to mention consumerism, which is, of course, tightly bound up with what it means to be a person in this place in time) that are produced in and through the redrawing of boundaries between ‘normal’ and ‘pathological’ accumulation.

So here goes – a few artifacts of order and disorder:

The DSM-V and Hoarding Disorder (300.3 [F42]). In previous versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), hoarding behavior stood as a sign or symptom of mental illness; as such, it was listed among the diagnostic criteria for a number of different disorders, including Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). In the DSM-V, however (the fifth and most recent edition of the DSM, which was released in May 2013), Hoarding Disorder emerged as a stand-alone disorder in its own right. Especially interesting to me is the extent to which this new disorder hinges upon a naturalized and normalized idea of the domestic interior and the ‘proper’ use of domestic space – indeed, the diagnosis seems impossible to make without a home at its center. Also noteworthy is the rigorous attempt made within this new entry to disambiguate pathological hoarding from ‘normal collecting’. Here Hoarding Disorder is described not only as excessive accumulation but as the improper management and organization of objects, as well as a fundamental misrecognition of their ‘true’ value (as if value were a natural and self-evident property of objects themselves).

The clutter management industry. A range of service providers enter the homes of their clients to put order to apparently disordered domestic spaces. Such services range from professional organizers and home consultants (who often imagine themselves as providing a form of therapy to their clients) to ‘Extreme Clean’ services, which are sometimes ‘offered’ by municipalities or social services as a last-chance option to persons facing eviction due to hoarding. It also includes the dynamic growth and visibility of the self-storage industry over the past several years, and the recent innovation of storage pods, or containers that are brought to a person’s front door to be loaded and are then whisked away to an on-site storage facility. The renter may then call the pod back to his or her doorstep at will, with 24 hours notice. Also falling into this category are retail chains like The Container Store, which sell objects whose sole purpose is to hold, carry, or keep other objects (shoes, laundry, wrapping paper, thumbtacks) in their place. Home and lifestyle magazines like Real Simple might also be included here for their demonstration of a very specific aesthetic of object management, at once rational but vigilant, detached but deeply caring.

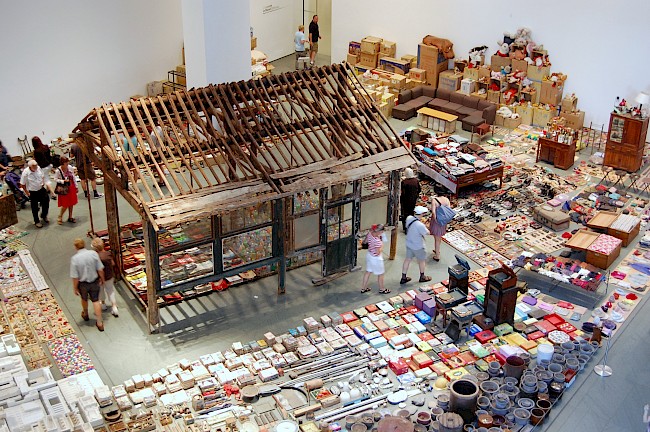

Song Dong’s Waste Not. This art installation, comprised of thousands of domestic objects that had been acquired, saved, and stored by the artist’s mother in her small house in Beijing over a period of several decades, was exhibited in New York, London, Vancouver, and Sydney, and elsewhere between 2005 and 2013. For Song Dong, the process of sorting through the undifferentiated piles and stacks with his mother at his side – and of placing all of the objects in neatly ordered rows – allowed for a kind therapeutic re-membering of the past; the objects themselves offered the very possibility of emotional healing. Nearly as fascinating as the exhibit itself were the reviews it generated and conversations it started, particularly in New York and London. While many made mention of modern Chinese political and cultural history, accumulation and consumerism, kinship, and care, many more fixated on the vast collection of objects as a clear sign of Song Dong’s mother’s pathological hoarding condition.

Photo credit: Andrew Russeth, Flickr

The Tiny House Movement. Over the past ten years or so, this rapidly growing movement has advocated simple, downsized living in architecturally innovative small-scale homes (generally under five hundred square feet). Inspired in part by Sarah Susanka’s 1997 book The Not So Big House, proponents of the movement suggest that tiny living spaces may afford people ‘more time and money for other areas of life such as marriage, family, education, fitness, and career. This helps create a more balanced and enjoyable life’ (Small House Society, http://smallhousesociety.net/about/). Recently, the movement has even inspired its own design show on TV called ‘Tiny House Nation’, airing on the FYI Network.

The Story of Stuff Project. The Story of Stuff is a short film that inspired a website, podcasts, an online resource bank, and a small social movement. With a focus on the effects of overconsumption on physical and emotional health, on social relationships, and especially on the environment, the movement promotes not just ethical consumerism (though this is celebrated as an important first step) but a move toward an engaged citizenship – not just ‘doing good’ but ‘making good’ – which is said to start with a fundamental shift in the way we live with and think about our world of stuff (The Story of Stuff Project, http://storyofstuff.org/).

There are, of course, many other artifacts and items of interest that could have been included here: contemporary interpretive practices of feng shui; TV shows like Hoarders and Hoarding: Buried Alive that present hoarding-as-spectacle; the DIY and Maker movements; city-wide hoarding coalitions that have sprung up throughout North America over the past ten years to address hoarding as a public health and safety issue; experiments in ‘collaborative consumption’ (community-level sharing); the Freecycling movement; and many more. Taken together, they suggest a deep preoccupation with the accumulation, order, and management of material possessions and an anxiety regarding the impact that our things, if improperly managed, might have on our mental health.