Loneliness and its opposite

Sex, disability, and the ethics of engagement

Don Kulick and Jens Rydström

— Reviewed by

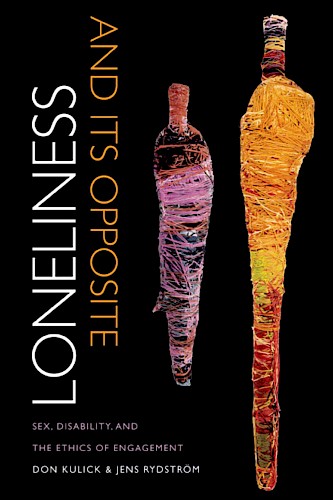

Don Kulick and Jens Rydström, Loneliness and Its Opposite: Sex, Disability, and the Ethics of Engagement. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015. Paperback, 376 pp., $26.95. ISBN: 9780822358336

Loneliness and Its Opposite opens with the story of Axel Branting, a Swedish man who offers counselling in the areas of sexuality and disability to people with a variety of physical or intellectual impairments. A woman asked Banting for advice: whenever her male care assistants lifted her out of her wheelchair to bathe her, she was sexually aroused. When the assistants noticed her arousal, they avoided lifting her and called upon female colleagues to bathe her instead. The woman’s dependency on personal assistants to help her experience her sexuality and her male assistants’ response to it are at the heart of the complexities that Loneliness and Its Opposite explores, namely, how are sexualities of people with cognitive and physical disabilities expressed, recognized, and facilitated, if at all? The authors’ approach to these pressing questions sets the book apart from other academic publications on disability and sexuality. Instead of endorsing a human rights-based approach to sexuality, Kulick and Rydström advocate a social justice framework, which recognizes that individuals’ exploration and development of their erotic awareness, sensations, and relationships require active assistance, through which sexualities, sensations, and sex can flourish.

The book’s core strength is the authors’ approach to sexuality, disability, and social justice. Emphasizing the importance of recognizing sexuality as integral to living a dignified life, the authors ask how, or if at all, people with disabilities receive state assistance in their explorations to realizing sexual lives. In the 1960s, a changing cultural zeitgeist, growing criticism of sterilization, and a move towards deinstitutionalization of the disabled all afforded people with disabilities greater legal protection and a wider range of different living arrangements. Amidst these transitions, the question of sexuality and disability, and how to accommodate people’s desires and needs, remained a private one, to be dealt with in the intimacy of the bedroom. Yet the conjunction of assistance, disability, and sexuality is particularly pertinent considering that disabled people’s embodiment and communication can challenge mainstream notions of agency and personhood, their lives may take place in group homes where boundaries between private and public are blurred, and institutions may actively prevent them from exploring their sexuality. The authors draw upon disability studies and crip theory but also criticize these for too exclusively foregrounding agency, empowerment, and ability in challenging stereotypes of dependency and disability. The authors emphasize that this focus on agency and empowerment might not fully take into account the fact that some individuals with certain cognitive and intellectual impairments do require assistance to live independently and to express their sexuality.

Kulick and Rydström draw upon the work of Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen to formulate their ‘capacities model’ of sexuality and disability. They quote Nussbaum, who writes:‘a just society is one that provides affirmative measures that help each individual develop his or her capabilities to the fullest extent possible’ (p. 281). Kulick and Rydström use Nussbaum’s social justice approach to move the discussion regarding sexuality and disability away from a static rights-based discourse towards a discussion of an active facilitation of people’s sexual needs and explorations.

The authors’ model is grounded in ethnographic research conducted in Denmark and Sweden, two Scandinavian postwelfare states that have addressed questions of sexuality, disability, and rights in different ways. In Sweden, advocates and policy makers do talk about sexuality but refrain from providing guidelines on how to facilitate this discussion, and many people who work with and care for people with disabilities also imagine that sexuality might be a potentially threatening and dangerous experience for people with disabilities. Sexuality is seen as a private issue and people with disabilities are to find their own ways to adjust to their environment. Denmark takes a different approach. There, since the 1960s, care workers have articulated a progressive approach to sexuality and disability that stresses that individuals with disabilities should have access to assistance to create fulfilling sexual lives. Denmark has set up state-sanctioned policies and guidelines that explain to care workers how to engage with people’s sexual needs without actually engaging in sexual practices. Some care facilities employ social workers who help people with disabilities draw up plans in which they can articulate their sexual needs and aspirations, and ways for the institution to facilitate these.

The strength of Loneliness and Its Opposite lies in the authors’ empirically and theoretically rich approach to sexuality and disabilities as questions of facilitation rather than solely of rights. They provide many examples of the different ways care workers and policy makers in two countries respond to people’s sexual needs. The authors document situations where some care workers refrain from discussing actual sexual needs, while others actively assist with sexual practices so that people can express and explore their desires. In my reading, the authors’ focus on the practices of facilitation resembles that of scholars in the field of care ethics, who stress that local solutions to specific problems in care need to be worked out, instead of providing universal principles of the good (Mol, Moser, and Pols 2010). Loneliness and Its Opposite points out that, just as care is a practice of doing, sexuality too is a practice that requires a sensitive and attentive experimentation with various bodies, parts, and people to help make sexualities and sexual practices possible. However, some people with disabilities might not appreciate Kulick and Rydström’s advocacy for the active engagement of the state in their private lives. They might experience sexuality as a personal affair that no person, besides their sexual partners, is to interfere with.

I am critical of the authors’ reading of disability studies and crip theory as insufficiently engaged with embodiment and lived experiences. It is partly because this scholarship has grounded disabilities in everyday lives and social contexts that the book’s discussion of sexuality and disability can take place. Despite this criticism, Kulick and Rydström make an important contribution in opening up debate, detailing various ways sexual and care needs of people with disabilities can be met, and situating sexuality as an actual activity wherein sexualities, pleasures, and objects are ‘tinkered’ with (Mol 2008) as part of ongoing efforts to live and create ‘good’ lives, both on an individual and a social level.

About the author

Marieke van Eijk is a lecturer in medical anthropology and global health at the Department of Anthropology, University of Washington. Their research and teaching interests sit at the intersection of transgender care, the workings of institutions, health care financing, and medical practices.

References

Mol, Annemarie. 2008. The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. London: Routledge.

Mol, Annemarie, Ingunn Moser, and Jeannette Pols, eds. 2010. Care in Practice: On Tinkering in Clinics, Homes, and Farms. Bielefeld: Transcript.