‘White man’s disease’

American Indian AIDS conspiracy theories and the refusal of synthesis

—

Abstract

Thinking about our experiences in AIDS research in postcolonial settings brings many images to mind, one of which is a half-gallon lunchbox. Made of clear plastic with a blue and yellow snap-lid, it is used to house numerous containers of antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) and the additional medications needed to soothe ART’s devastating side effects. Medicine bottles filled with pills and liquids, stored together inside plastic lunchboxes, purses, cloth totes, and plastic shopping bags, are ubiquitous in the homes and social spaces occupied by people living with HIV and/or AIDS (PLWHA) across the globe. This is especially the case among historically oppressed populations, where the legacies of colonialism, racism, and social exclusion continue to make people vulnerable to HIV infections (Negin et al. 2015). The particular lunchbox that comes to mind belongs to a Cherokee man living with HIV. A survivor from the initial days of the epidemic, Tim is a fit and muscular man, showing no hint of frailty because of the virus. Conducting anthropological fieldwork with gay American Indian men, some of whom identify as Two-Spirit, the lead author came to know numerous PLWHA, but most stood in stark contrast to Tim’s good-health status. Instead, many were visibly ill, their gray skin taught and translucent, stretched over bones; their bodies were reflective of epidemiological data that reveals consistently high rates of mortality and poor HIV and health outcomes among American Indians (Negin et al. 2015; Pearson et al. 2013). Tim’s body showcased his ability to engage successfully in self-care, but hardly represented the majority of Native[note 1] people who were visibly more fragile and who were often treated as ‘walking dead’. Only Tim’s lunchbox of medicines gave away his seropositive status. Though he was not attempting to hide it, his obvious good health and vivaciousness made his HIV status all the more shocking. Over the last fifteen years, many of the people encountered by the first author in the early months of fieldwork have passed to the other world from AIDS-related complications. Formerly HIV-negative people are now positive, and some are living in ways that will ensure their lives are short.

Tim’s exceptional health, good looks, and education made him an excellent spokesman for the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Indian Country. He did not possess the overt anger of many of the other HIV-positive men, and he was able to articulate the impact of the disease on his life in a way that many of the others could not. Many of them were addicted to alcohol or drugs, had held low-wage jobs before they were infected, and/or were on disability. Some became infected while engaging in sex work to supplement their meager incomes. In explaining how they got infected, many men drew links between their need to escape homophobia in their communities and their migration to urban centers. This and other chains of causality woven by the men seldom sought to relieve them of the personal responsibility of becoming infected; instead, they served as a way to explain what one extremely sick HIV-positive Kiowa shared: ‘You put anyone in those circumstances and they’re gonna get infected’. The people around Tim who were also living with HIV/AIDS saw themselves as having a common bond with him, yet simultaneously recognized that different forces were at work in their lives and disease trajectories. For example, Tim had been a well-known fixture in the 1980s’ upper-class, urban gay scene, comprised mostly of White gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (GLBTQ) professionals. Furthermore, unlike most of the other Native men, Tim’s family had accepted his diagnosis and put a significant amount of work into supporting him, which no doubt helped bolster his public role as an American Indian living with HIV/AIDS (AILWHA). Despite the fact that his circumstances were unusual, Tim became the ‘center’ against which other infected Native men were compared and pushed to the margin. He became the ‘go-to man’ for anything dealing with American Indian HIV/AIDS issues and sat on the committees and boards of multiple awareness and prevention organizations, at the state and the national level. The numerous unnamed and largely unknown infected beamed with pride when they saw Tim interviewed by local television stations on World AIDS Day or were present when he spoke at a public function. Tim’s very public and seemingly good fortunes, however, diverted the attention of policy makers and advocates away from focusing on how marginalized AILWHA and their communities understood HIV/AIDS, and why they might oppose the logics of standardized biomedical and public health HIV/AIDS knowledge and practices.

Tim and his local network of Native AIDS workers saw themselves in a continual battle against what they often described as the ‘ignorance of our own people’. Education, they argued, was the only way to combat the spread of infection among the most vulnerable Natives. They were horrified when told of the conspiracy theories that HIV/AIDS was a ‘White man’s disease’, offered as part of interviews held with AILWHA and their friends and family members. The research highlighted here was part of a project funded by the US Health Resource Service Administration (HRSA) that sought to understand why Native peoples living with HIV/AIDS resisted care even when it was free. The lead author, with research assistants, collected the data during interviews within the homes of individuals who responded to posters in public spaces fanning across Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, New Mexico, and Colorado. Many of those interviewed shared conspiracy theories about the origins of AIDS, which were recorded and later analyzed by both authors to conceptualize and write this article.

Interviewees overwhelmingly saw HIV/AIDS as a ‘White man’s disease’ and cited multiple reasons why non-Natives were responsible for its spread across Indian Country. Learning of this interview data, the clinic staff and associated HIV/AIDS educators responded with the same call for more education and strategic efforts to overturn such ‘ignorant’ beliefs. Some advocates saw the characterization of HIV/AIDS as a ‘White man’s disease’ as an obstacle to efforts seeking parity for treatment, patient rights, and access for AILWHA. For them, naming AIDS a White man’s disease was a form of denial about its potential effect on the Native community, as well as a form of racialization that alienated HIV-positive Natives from their communities.

Over time we began to see such conspiracy theories as a window through which to understand HIV/AIDS from the perspectives of many AILWHA and their friends and families. In this article, we argue that to simply interpret such conspiracy theories as stemming from a lack of technical and scientific knowledge about HIV/AIDS or as a form of denial is to miss an opportunity to carefully consider what people seek to accomplish when they offer such narratives. Instead, we suggest, these HIV/AIDS conspiracy theories served not only as astute social critiques but also as a way for a community to slowly incorporate the disease into its own understanding of social, political, historical, and moral circumstances. Native AIDS workers’ reactions revealed how highly local and nonstandard views of the disease were pushed to the margins. Through subscribing to conspiracy theories, we discovered, many community members refused certain aspects of AIDS prevention, education, and intervention. Standard HIV/AIDS-related prevention and treatment programs tend to universalize experiences with and responses to the AIDS epidemic and to ignore – or push to the margin – alternative framings and understandings. In Natives’ refusal to synthesize their own experiences with national and international AIDS ideologies, we see a tension between centers and margins, influenced by their interactions with universal, individual, and community notions of care, AIDS, and health causality. The use of conspiratorial narratives by American Indians, we argue, disrupts the individual, humanist element of settler logic that attempts to universalize AIDS and community experiences. By making AIDS a ‘White man’s disease’, Natives foreground a particular historical trajectory of social and health neglect by the settler state, and refuse to equate and collapse their own marginalized experiences and understandings of HIV/AIDS with dominant knowledge about the disease.

We use the term ‘synthesize’, with its roots in Hegel’s (1969) theory of dialectical reasoning, to formulate a challenge to much of the theorizing about HIV/AIDS that adopts a Marxist framework. In Hegel’s theory, synthesis occurs when a thesis is challenged by a counterthesis; these come together to form a new idea. Dialectical reasoning is a key process in Marx’s theory of revolution: the rise of the proletariat will synthesize the classes and produce a society without inequity. Dialectical reasoning is a common philosophical underpinning of Marxist theoretical approaches in the study of HIV/AIDS, found in the notions of ‘structural inequality’, ‘structural violence’, and other ways of understanding indirect forms of oppression. But these Marxian foundations within HIV/AIDS anthropology contain many assumptions about HIV/AIDS and the sociocultural mechanisms at play. For example, in the history of HIV/AIDS scholarship, a dominant thesis was that the spread of HIV/AIDS was the result of poor choices made by ignorant people. An anthropological counterthesis argued that larger forces, such as structural inequality, were involved. Anthropologists who subscribed to the notion of structural violence then synthesized key public health ideas about education and risk with the explanatory mechanism of structural inequality, producing a powerful analytical tool and potent political critique. But how does this theory of synthesis help us analyze social mechanisms in societies that do not use dialectical reasoning to understand forces of inequity and power differentials? We contend that synthesizing a Western political critique with local understandings of the power relations of HIV/AIDS infection diminishes the explanatory power of indigenous disease theories.

Conflicting explanations of HIV/AIDS

In the spring of 2009, in Washington, DC, a group of experts was convened for three days by the HRSA to consult on the reauthorization of the American Indian portion of the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act, also known as the CARE Act. The primary goal was to create a comprehensive, coherent, and effective argument for why the special American Indian provision in the CARE Act should continue, instead of being grouped into other, broader minority initiatives. The first author attended these meetings, where top officials at HRSA were present and appeared genuine in their desire for information and strategic thinking, as they believed that keeping the Native provision was crucial for the continued treatment of AILWHA. The group of advisors included community health workers, HIV/AIDS political organizers, leaders from the HIV/AIDS prevention movement, and academics who were researching HIV/AIDS within Native communities. The impressive group covered a broad range of US tribal geography as well as a broad range of academic disciplines from public health, social work, medicine, and anthropology. As soon as the meeting started, the assembled group skipped any niceties and quickly took full advantage of the presence of high-ranking officials to voice their concerns.

HRSA had invited participants to voice concerns and give opinions, based on their wide range of experiences and expertise. However, the meetings quickly spiraled into one oratory after another on the imposition of colonialism, the intentional infection of nineteenth-century communities with smallpox, and the federal government’s neglect of Native peoples. Many Native participants and experts connected the AIDS epidemic to the legacies of oppression, disenfranchisement, and health neglect experienced by those living in Indian Country. In so doing, they were pointing to the distinct and ongoing challenges facing Native communities. In many ways, the sentiments offered during this meeting echoed the logic and roots that had created and sustained the conspiracy theory that AIDS was a White man’s disease. The HRSA staff listened patiently while divisions between the meeting attendees grew deeper. The refusal of consensus and the difficulty in neatly and swiftly couching these claims in the more standardized language used in AIDS programming unfortunately meant that the group moved further and further away from being able to save the American Indian provision in the CARE Act. In retrospect, it seems that the conflicts during this meeting were a product of a disconnect between a community process and federal government process, which was perhaps not unusual given the long history of misunderstanding and bitterness between Natives and the federal government. However, the HIV/AIDS crisis had somehow inspired certain government agencies to work more successfully with Native communities, and the first author found it frustrating and difficult to watch as the potential to renew the American Indian provision became lost in the rhetoric about colonialism and the government’s treatment of Indians.

Attendees linked land disputes to poverty and to high infection rates, seeking to explain how and why HIV was so prevalent in this population. These linkages were consistent findings in the available research, and were well known by the majority of the officials present, most of whom came from minority communities with similar issues. The constant articulation of these more non-standard linkages just mentioned, however, appeared to overwhelm government officials. Throughout the meeting, multiple agency division chiefs faded, with their eyes half closed, as one participant connected the annexation of the Black Hills to increased HIV infection rates and poor care for AILWHA among the Lakota and Dakota peoples. Another spent nearly an hour detailing why the meeting was not a ‘consultation’ and should not be called a consultation because in her tribe ‘consultation’ meant something quite different. By the second day, the group had nothing of substance – at least from the perspectives articulated by government officials – to support the need for continued funding of AILWHA-specific initiatives. At the meeting, Native understandings of the impact of the disease were pushed to the margins of the dominant and universalistic conceptions of AIDS prevention, education, and interventions.

It seems that within the efforts to address the distinct challenges of HIV/AIDS among American Indians a tension existed between opportunities to be heard and opportunities to get things done. Concern for AIDS treatment and HIV prevention in Indian Country did not emerge in any significant way until the early 1990s, although urban grassroots organizations such as Gay American Indians in San Francisco had been working on behalf of AILWHA beginning in the mid-1980s (Roscoe 1998). On reservations and in rural areas with Native concentrations, AIDS care and advocacy work mostly fell to local caregivers. A handful of concerned Native health care providers, mostly women and GLBTQ Natives, took it upon themselves to care for the AILWHA in their communities and to push tribal leaders for prevention and treatment programs. The Indian Health Service, the wing of the federal government responsible for providing care to members of federally recognized tribes, did not fund prevention programs until the late 1980s. Despite local advocates’ efforts, the particular challenges of AIDS among Natives went largely unnoticed by legislators and funding agencies until 1996 when the CARE Act began distributing funds to tribal governments and nonprofit organizations working among Native people (Vernon 2001).

Unfortunately, specific provisions regarding care for AILWHA were removed in the 2009 renewal of the CARE Act. The increase in AIDS awareness and federal funding to tribal governments for AIDS treatment and HIV prevention coincided with an increase in the institutionalization of addressing the AIDS epidemic among Native populations.

The institutionalization of HIV/AIDS efforts on behalf of Native Americans

From its initial days in the 1990s to the present, the Native AIDS industry (see Nguyen 2005; Patton 2002) has developed several formal and informal institutions. One of the most important AIDS institutions in the Native-dense (relatively speaking) central-west region of the United States are the local experts who have some personal connection to HIV/AIDS: they may be infected themselves, have a close friend or family member who is or was an AILWHA, or work providing care and serving as an advocate. An essential part of doing these many forms of AIDS work in Indian Country is providing a social space and social networks that articulate Native cultural values, and that is protected from the watchful and judgmental eyes of the tribal community.

The other very important institution is the AIDS support group; these are often associated with Indian Health Service clinics or with local nonprofit and grassroots organizations such as Two-Spirit societies. They exist throughout the United States, but are more concentrated in the West. Support groups cross rural-urban divides in that many members of support groups will travel from their rural and suburban homes to attend group meetings and activities in urban places, which provide opportunities to escape the isolation so common among AILWHA. They are usually multitribal in their focus, though larger tribes like the Navajo have their own organizations, such as the Navajo AIDS Network. Groups offer Native programming and culturally specific activities as a way of building community but also as a way for service workers to care for AILWHA and high-risk individuals. Support groups also act as hubs from which spokes radiate to smaller support groups that are clustered regionally and across states. This network of AILWHA, GLBTQ Natives, care providers, advocates, and concerned friends and family of AILWHA are all connected through regular meetings, retreats, and social activities oriented toward prevention and awareness, such as AIDS-specific powwows and ceremonies, as well as email lists and websites.

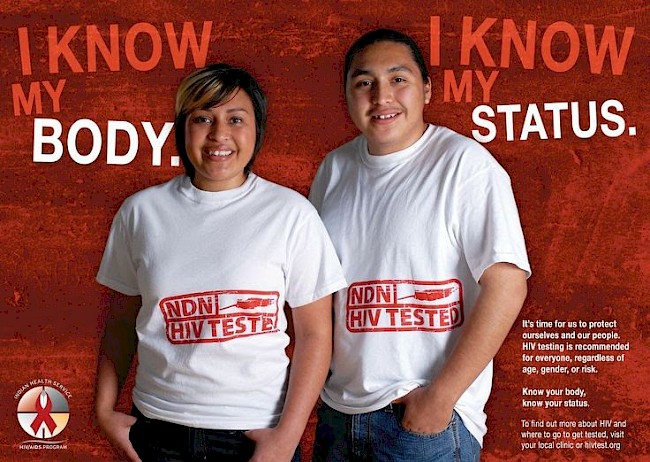

Within this multitribal context, the American Indian AIDS industry has centralized its efforts to expand prevention and treatment programs using mostly federal aid in the form of grants and service contracts. Prevention training targeting at-risk populations among Natives – adolescents, GLBTQ people, street-level alcohol and drug abusers, sex workers, and the homeless – is the primary source of HIV/AIDS knowledge for American Indians. These prevention programs disseminate what Patton (1990) calls ‘standard AIDS knowledges’, which are the agreed-upon principles among scientists and medicine and public health workers about HIV/AIDS. Such standard AIDS knowledges include basic information on routes of transmission and how to protect oneself, known as ‘HIV 101’. The disconnect between standard AIDS knowledges and American Indian cultural values and perspectives made prevention difficult in the early days of outreach. However, a number of committed scholars effectively transformed understandings about accepted Native AIDS knowledge. This body of work recognizes the unique socioeconomic and political situation of American Indians, and most of the guiding principles developed for AIDS outreach and care among this population are based within research and activism by Natives (see, for example, Burks et al. 2011; Gilley 2006; Nakai et al. 2004; Walters and Simoni 2009; Walters et al. 2012).

Seeking parity in prevention and treatment resources required activists and community health workers to conceptualize Native-specific HIV/AIDS issues through the lens of standard AIDS knowledge. Additionally, all HIV/AIDS work among Natives had to adhere to the international best practices of community-based treatment and prevention, which meant singling out specific perceptions of disease risk and disease treatment as counterproductive to containing the virus. Unfortunately, the creation of Native-specific AIDS knowledge increased the tendency to place cultural conservatism, tradition, and other community habits in opposition to effective HIV/AIDS prevention (Mitchell et al. 2002; Ramirez et al. 2002; Sears 2002). Local community ideas about the inappropriateness of discussing sexuality in public, and of elders discussing sexuality with youth, and practices of gender segregation were all targeted as potential barriers to HIV education for Indians. Two issues, in particular, were seen as the most dangerous for AIDS prevention. First, Natives were reluctant to use, purchase, and discuss condoms; second, Natives tended to characterize AIDS as a White man’s disease. The notion of ‘racial susceptibility’, or the idea that some populations are inherently vulnerable to HIV infections because they belong to a particular racial category, was seen as further supporting Native reluctance to use condoms as a preventive measure. Indeed, these perceived barriers, and their intersections, continue to be the basis of concern and biomedical research among a variety of minority groups in the United States today (see, for example, Ford et al. 2013; Ross et al. 2006).

According to research conducted over the last twenty years, Native Americans continue to have disproportionately high per capita rates of HIV infection (CDC 2016; Conway et al. 1992; Metler et al. 1991). Speculations about the cause of this disparity focus on poverty, lack of education, drug and alcohol abuse, tribal diversity, and health care disenfranchisement. Among the most speculated but least researched causes are Native American ideas about disease and race. It has become conventional wisdom among human services circles that Native people resist HIV-prevention efforts because they view HIV/AIDS as a ‘White man’s disease’ – an import of European contact and cultural influence – and conceptualize it in similar ways to colonial-era smallpox epidemics and the introduction of alcohol. The notion that HIV/AIDS is acquired by White behaviors, such as intravenous drug use, and that it is localized in White-dominated places, such as major cities, intensifies the mystification of the disease.[note 2] The ways in which race, class, tribal affiliation, and sexuality intersect with Native ideas about disease causality further determine how HIV-positive individuals may be treated by their communities and tribal-based health care services. Individuals who are infected may be viewed as ‘less Indian’ or as being punished for deviating from community values by engaging in ‘White’ activities such as homosexuality or intravenous drug use (Kopelman 2002). These ideas about HIV/AIDS create resistance to prevention programs and difficulties in designing and implementing HIV/AIDS-prevention outreach to Native communities (Vernon 2000; Vernon and Bubar 2001; Weaver 1999).

Scholarship on HIV/AIDS among Native Americans

The small amount of research concerning Native Americans and HIV/AIDS focuses on the ways racial difference is associated with environments of risk, and is largely reflective of the academic interest in risk-related behavior (Parker 2001). The environment of risk perspective conceives Native peoples as more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors because of their cultural and socioeconomic environments, and concludes that Natives are more likely to engage in risky behavior because of certain racially linked cofactors, such as drinking, intravenous drug use, and lack of condom use. One example is the link that the CDC (1994), Fenaughty and colleagues (1998), and Vernon (2000, 2001) have made between Native people and substance abuse and HIV infection risk. These studies concluded that Native people were more likely to put themselves at risk for contracting HIV/AIDS by ignoring protective factors while under the influence of alcohol or drugs or engage in needle sharing. In making these conclusions, they draw on racial identity as a marker for risk behavior or living in an environment of risk. These studies, as well as others (Baldwin et al. 1996; Vernon and Bubar 2001; Weaver 1999), also found that Natives conceive of HIV/AIDS as a disease explicitly associated with ‘White’ behaviors, such as homosexuality and intravenous drug use. While they address Natives’ denial that such risk behaviors take place within their culture and communities, they do not address the role of racial essentialism in Natives’ belief that they are racially unsusceptible to infection. That is, they do not consider why and how Natives construct beliefs about HIV/AIDS as a disease explicitly associated with race and how this association affects perceptions of risk or how they think about and engage with the disease.

In contrast, some anthropological research examines the disease from the perspective of the people deemed most ‘at risk’ (in Haiti: Farmer 1992, 1999; in Africa: Schoepf 1988; Setel 1999; Pfeiffer and Maithya 2016). Foundational research theorizes that individual risk assessment resides at the nexus of cultural ideas about disease causation and political-economic factors, and reveals how structural factors relate to the social vulnerability of individuals and groups (Dilger 2003; Farmer 1999; Feldman 1994; Parker 2001). Scholars argue that individuals assess their risk for HIV/AIDS from a subordinate socioeconomic-political position (Dilger 2003; Farmer 1992, 1999; Kopelman 2002; Parker 2001; Romero-Daza et al. 2003). Therefore, individual notions of risk as they relate to conceptions of race are filtered through socioeconomic inequality. For example, Farmer’s (1992, 1999) work in Haiti shows that rural people theorized AIDS as a tool of ‘White’ political and social domination, brought by America and Europe in cooperation with the Haitian upper class. Although race thinking is not central to Farmer’s arguments, he points us in a direction of additional research: how subordinate groups potentially view HIV/AIDS as a socioeconomic issue and as a marker of racial difference.

Building upon anthropological work that illustrates how HIV/AIDS is racialized as an aspect of structural inequality (for example, Fassin 2007 in South Africa; Sangaramoorthy 2014 in the United States), we consider how individuals conflate notions of racial characteristics into conceptions of disease susceptibility, but within the discursively constructed ‘morality’ associated with race. While Natives understand the biological mechanism through which HIV is transferred from one human to another, for many, ‘why’ Natives get HIV and die of AIDS has its causal roots in the moral differences between Indians and Whites. It is another disease in a long line of hardships brought to them by colonization and the settler, an epidemic of White moral origins that is spread to further the sociopolitical domination of European Americans.

Natives interviewed as part of the research presented in this article believed that they had been free of many infectious and endemic diseases prior to the arrival of Europeans. Smallpox occupies a mythical status among Native people for its overwhelming devastation of indigenous populations, its distinct link to contact with non-Natives, and its use a tool of colonial domination. In the late 1980s, when the first cases of AIDS were appearing in IHS hospitals and clinics, the disease was being referred to as ‘the next’ or ‘the new’ smallpox. By conceptualizing AIDS as an impending health disaster on the scale of European contact, Natives immediately placed it in the conceptual realm of the moral, social, and political failings of non-Natives who were responsible for colonization. Viewing AIDS in this way links the contemporary HIV/AIDS experience with historical understandings of American Indian health, and facilitates conspiratorial theories that place the origins of AIDS and its spread among Natives within White society.

Farmer’s (1992, 235) ‘hermeneutic of generosity’ asks us, ‘What might happen if we were to proceed as if our informants were themselves experts in a moral reading of the ills that afflict them?’ Accordingly, we propose that Natives’ conspiratorial thinking about AIDS is a moral reading intended to explain in experiential terms why American Indians are subject to HIV, a disease they perceive as having origins in and causes external to their communities. Hellinger (2003, 205) argues that such local ‘truths’ are therapeutic for the disempowered who do not possess the same information and structural position as the more powerful. Dialectical anthropology argues that conspiracy should be thought of as a locally generated remedy to the disjuncture between what the disadvantaged experience and what they are told about that experience by individuals in power (Harding and Stewart 2003, 259–60).

Tribal locals use conspiracy theories to supplement, replace, and challenge the information received from ‘above’ by providing other explanations (Butt 2005; Gilley and Keesee 2007; Keeley 1999). Received information, emanating from political struggles between ruling and powerless classes, has a generative quality whereby competing theories or rumors become local understandings of global projects (Farmer 1992, 204; Feldman-Savelsburg et al. 2000, 160). The social upheaval created by projects bigger than ‘the locals’ and the associated inequalities are thought to generate nuanced and symbolically rich discourses that provide insights into political conditions (Taussig 1980, 117). Rumor and conspiracy theories, then, are ‘forms of explanation for social and material exchanges that defy conventional practical reason’ and are generated at the disjuncture between local experience and global flows of power-capital (Butt 2005, 417).

We extend this analysis by proposing that conspiracy theories are also able to generate their own disjunctures; in this ethnographic context, they are aimed at disrupting the synthesis of health experiences of subordinate and dominant groups. Among American Indians affected by HIV/AIDS, conspiracy theories act to interrupt public health discourses claiming to know the universal origins of HIV/AIDS. They resist a dialectical logic within public health knowledge that mystifies the problems associated with AIDS facing American Indians by wedding it to standard AIDS knowledge. Native conspiracy theories about AIDS interrupt the dialectics of accepted public health theories at the crucial moment when American Indian AIDS knowledge is being synthesized into the universality of standard AIDS knowledge. By claiming a ‘White’ etiology for AIDS as (1) the intentional infection of Natives by the US (read White) government through biological agents and (2) the infection of Natives through moral contact with Whites, American Indians are synchronizing the AIDS epidemic with a particular historical trajectory of domination and health neglect.

‘White man’s disease’

Among those working in the Native AIDS industry, any deviation from accepted public health theories is considered a sign of failure in AIDS prevention and treatment education. Native community health workers were exasperated when Ben, an ethnographic assistant for the research described in this article and a member of the Osage tribe, read from an interview transcript: ‘I think it’s from Europeans. I think a lot of people, you know, when they came to this country, and all this disease they brought, they brought in their toxins and their poisons, and not just physical but social and spiritual’. Their dismay increased as Ben recounted the numerous statements he had collected that asserted that ‘the White man created AIDS on purpose’.

Ben and John, another gay American Indian man and research assistant, had conducted interviews with American Indians affected by the AIDS virus, and these exposed a great deal of anger toward the US government, tribal governments, and fellow tribespeople on the part of AILWHA, their family members, and community advocates. Nearly one-half of the sixty interviewees maintained sentiments that AIDS was a ‘White man’s disease’. For example, a forty-three-year-old Kiowa woman shared, ‘You hear all kinds of things brought here from the monkeys from Africa, and then too may hear just incredible theories about maybe it’s the government tryin’ to finish us off or thin out the ethnic, you know, Blacks, Hispanics’. While this participant did articulate a common theory for the origins of AIDS pushed by the AIDS industry – that it originated in primates in sub-Saharan Africa – she also mentioned the possibility that AIDS was a tool being used by the American government to purposefully eradicate Native and other minority populations. Likewise, a forty-nine-year-old woman from Laguna Pueblo recited a dominant public health explanation used to explain the emergence of the epidemic, but ultimately rejected it in favor of what she described as a ‘way out there’ narrative that was more convincing and useful from her social and moral positioning at the margins. In response to the question, ‘Where do you think HIV came from?’ she said:

I just finished reading Leslie Marmon Silko’s book, Almanac of the Dead, and I tend to, sort of, I know it’s way out there, but tend to agree that I think – because the virus mutates and therefore we’ve been unable to get a vaccine or anything going with it ’cause it mutates constantly – I-I believe it was some sort of genetic engineering. Whether it was for whatever reason, chemical warfare or whatever, I think either it was introduced on purpose into the population or it was accidentally leaked out and got in the population. She also makes reference to hepatitis B and C also being invented and introduced into the population. They also mutate very weird. We’ve got C, D, E, F, G, H now, so I tend to think it was man-made. I’m not really buying the little Ebola-type monkey thing. I think it was some sort of genetic engineering, for whatever reason. There are theories that the CIA introduced it into certain populations to try to wipe ’em out. I don’t know.

While she expressed confidence in the idea that HIV was man-made, she seemed less sure of or concerned with the exact reasoning for why it was made. This statement, and others like it, demonstrates agency in refusing to ‘buy into’ claims about the origins of the virus, and instead linking the epidemic to a novel’s history of America from the perspective of the oppressed. Silko’s book provides a moral critique of European American values and the associated medical complex that uses disease for genocidal purposes. By connecting HIV to this text, the woman interviewed situates the AIDS epidemic within the context of the colonial domination of American Indians. She identifies domination as an ongoing struggle, thus allowing for the possibility that the government might have intentionally introduced HIV – a virus that mutates so rapidly it cannot be cured – into the Native population to ‘wipe ’em out’.

A forty-three-year-old HIV-positive Cherokee man, in response to the same question, initially stated that he didn’t have a clue. But he immediately continued and mentioned past atrocities committed by Whites against minorities:

You know, I don’t know. I don’t have a clue. The one thing that comes to mind, I’ve heard that maybe some of the unethical and horrible things that our government did to some minorities – there was even a name for it and I can’t think of it – that possibly somethin’ stemmed from some of their, I don’t even know what you call it, it’s not genetic testing but something like that, where they were putting different viruses in minorities.

By bringing the AIDS epidemic in line with historical social and health experiences, the conspiratorial thinking presented above demonstrates a rejection of universal theories about the origins of AIDS – which do not specifically explain how or why HIV penetrated the Native community – in favor of a distinct AIDS etiology that resonates with the perspectives and experiences of many marginalized members of Native communities.

These types of narratives are also used to explain why the disease continues to wreak havoc in Native populations. Instead of following standard knowledge about HIV, interviewees focused less on the risky behaviors of Native Indians and more on the neglect of non-Native experts, who were perceived as unwilling to dedicate the resources necessary to eradicate the disease. These sentiments can be seen in the words of a forty-seven-year-old HIV-negative Mvskoke Creek man:

They still haven’t done anything about it, and they won’t do anything about it. There’s more cures for baldness, bad breath and skin, cosmetic crap, than there is for these deadly diseases. They don’t want anybody to have it. They just refuse to try to fix it. They start wars to kill more people, ’cause the AIDS and stuff they invented aren’t killin’ ’em quick enough.

But the common sentiment that AIDS is a ‘White man’s disease’ was not limited to narratives about the government infecting Native Indians with biological agents and refusing to seek a cure. Others rooted the origins of AIDS in more spiritual terms, offering a moral reading of the historic and ongoing consequences of the long-term, destructive practices and ideologies of the dominant, capitalistic society. For example, a forty-four-year-old HIV-negative Pawnee man explained things this way:

It could be that the virus comes from what you read in a lot of Native American books, because you’re going into the rainforest, where things live, and you’re goin’ down there and choppin’ everything all up, you’re not respecting Mother Nature. … And I think when you get deep into the rainforest, there lurks stuff there, from what I’ve read, that there’s stuff that lurks there. So you get to choppin’ it down and put houses in there, well, look what’s gonna happen.

For this man, new diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, were a logical consequence in a long history of moral contact with European American ideologies, values, and culture that continued to exploit and abuse Mother Nature, the sustainer of all life and health, for socioeconomic and political gain. The relentless and disproportionate suffering from HIV/AIDS among American Indians thus gets interpreted as an imposition of settler colonialism, a project that continues to entangle the lives of Natives and non-Indians, and does so in ways that dispossesses and ‘marks’ the Native population for destruction (Morgensen 2011; Simpsen 2016). By locating the origin and persistence of AIDS within this particular context, this interviewee articulates a resistance to standard AIDS knowledges and refuses to collapse his own, more marginalized experiences and understanding of HIV/AIDS into dominant ideologies about the disease.

Conspiracy theories, negation, and cultural continuity

Comaroff and Comaroff (1993) and Taussig (1980) suggest that conspiracy theory and rumor speak from localities decentered by modernity and capitalism. But understanding that conspiracy theories emanate from a need to explain the conditions of disempowerment is only part of the story. Their function may not always be as a ‘weapon of the weak’ (Scott 1987) or as a way to displace, dampen, or replace oppressors; they can also function to reify an understanding of social position, a position from which all local social and political understandings originate. Boyer’s (2006, 332) recent work on men’s political meetings in Germany, known as stammtisch, tells us that ‘conspiratorial knowledge [is] sought not only to reveal, to assert intellectual agency but equivalently to disrupt knowledge, to cultivate doubt and uncertainty around a logic of historical inheritance already familiar to all’.

In the context of Native understandings of AIDS, conspiracy theories are voiced to assert ‘intellectual agency’ over problems, but their goal is not to disrupt or create doubt. Rather, their goal is to cultivate continuity ‘around a logic of historical inheritance already familiar to all’: the historical inheritance of colonial domination. Conspiracy theories incorporate new experiences into this historical inheritance by creating continuity among all Native ‘problems’. In order for AIDS to be adequately incorporated as a ‘problem’ it must have the same historical, social, and political underpinnings as the other ‘problems’ faced by Native communities.

In Boyer’s (2006, 331–32) ethnographic context, the ‘source of anxiety was not too little knowledge, but too much, in which the haunting is a matter of the unforgettable as opposed to the unknowable’. In this same way, Native AIDS conspiracy theories do not function to fill in the ‘unknown’ aspects of the AIDS problem but rather to reify the ‘unforgettable’ fact that all health problems among Native communities, large and small, articulate in some way with a history of colonization and a continued state of social, political, and economic disenfranchisement. The AIDS crisis is constructed as a uniquely Native one, giving it the same sociopolitical origins as other ‘crises’. The efficacy of such Native AIDS conspiracy theories comes not from a critical response to a Native health crisis, but rather from its ability to give AIDS a discursively consistent historical background and causality.

In this context, AIDS makes more sense as a continuation of attempts by the US government and Whites to wipe out American Indians and their culture. For individuals who use conspiracy theories, it makes absolute sense that the government would designate Natives as a ‘high risk population’ for HIV infection, that it would underfund programs combatting its spread, and that the IHS would not carry drugs needed by AILWHA in their pharmacies. The claim that White people brought AIDS to Native communities by purposeful infection and moral degradation is founded within a set of circumstances specific to Natives’ history, in which non-Natives over and over again have pushed Natives to the margins. In this way, conspiracy theories are less of a critique and more of a model of continuity. In this case, conspiracy theories further create continuity with the past by refusing to synthesize the contemporary Native AIDS experience with that of non-Natives, an act that would divorce AIDS from the colonial experience. By bringing AIDS into line with other historical Native health crises, they are interrupting what Hegel (1969, 126) called the ‘negation of the negation’. They are finding agency in the interstitial space between the counterthesis and the synthesis and exploiting this thought moment.

About the authors

Brian J. Gilley is Professor of Anthropology at Indiana University, Bloomington. Dr. Gilley has conducted extensive research on gender, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS among American Indians (specifically GLBTQ: 2-Spirit), as well as on performance-enhancing drug use among collegiate and professional cyclists. Dr. Gilley’s most recent projects investigate the role of affinity between the Italian colonies and the homeland. This ethnographic and historical research includes projects on the colonial uses of sport during the interwar period, body nostalgia among vintage sport enthusiasts, and the creation of a pan-Mediterraneanism between North Africa and Italy.

Elizabeth J. Pfeiffer is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Rhode Island College in Providence. Dr. Pfeiffer broadly conducts anthropological research on globalization, infectious diseases, youth, and gender and sexuality in Kenya, Jamaica, and the United States. Her primary ethnographic research and current book project explore the intertwining linguistic, social, and structural roots sustaining HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in a highway-trading center in western Kenya during a period of increased access to HIV services.

References

Baldwin, Julie A., Jon E. Rolf, Jeannette Johnson, Jeremy Bowers, Christine Benally, and Robert T. Trotter. 1996. ‘Developing Culturally Sensitive HIV/AIDS and Substance Abuse Prevention Curricula for Native American Youth’. Journal of School Health 66, 322–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1996.tb03410.x.

Boyer, Dominic. 2006. ‘Conspiracy, History, and Therapy at a Berlin Stammtisch’. American Ethnologist 33, no. 3: 327–39. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2006.33.3.327.

Burks, Derek J., Rockey Robbins, and Jayson P. Durtschi. 2011. ‘American Indian Gay, Bisexual and Two-Spirit Men: A Rapid Assessment of HIV/AIDS Risk Factors, Barriers to Prevention and Culturally-Sensitive Intervention’. Culture, Health & Sexuality 13, no. 3: 283–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2010.525666.

Butt, Leslie. 2005. ‘“Lipstick Girls” and “Fallen Women”: AIDS and Conspiratorial Thinking in Papua, Indonesia’. Cultural Anthropology 20, no. 3: 412–42. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2005.20.3.412.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1994. ‘Heterosexually Acquired AIDS-United States, 1993’. Morbidity, & Mortality Weekly Report 43, 155–60.

CDC. 2016. ‘HIV/AIDS among American Indians and Alaska Natives’. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/aian/.

Comaroff, Jean, and John Comaroff. 1993. ‘Introduction’. In Modernity and Its Malcontents, edited by Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff, xi–xxxvii. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Conway, George A., Thomas J. Ambrose, Emmett Chase, E. Y. Hooper, Steven D. Helgerson, Patrick Johannes, Myrna R. Epstein, Brent A. McRae, Van P. Munn, Laverne Keevama, Stephen A. Raymond, Charles A. Schable, Glen A. Satten, Lyle R. Petersen, and Timothy J. Dondero. 1992. ‘HIV Infection in American Indians and Alaska Natives: Surveys in the Indian Health Service’. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency 5, no. 8: 803–809.

Dilger, Hansjörg. 2003. ‘Sexuality, AIDS, and the Lures of Modernity: Reflexivity and Morality among Young People in Rural Tanzania’. Medical Anthropology 22, 23–52. http://doi.org/10.1080/01459740306768.

Farmer, Paul. 1992. AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Farmer, Paul. 1999. ‘Pathologies of Power: Rethinking Health and Human Rights’. American Journal of Public Health 89, no. 10: 1486–96.

Fassin, Didier. 2007. When Bodies Remember: Experiences and Politics of AIDS in South Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Feldman, Douglas A., ed. 1994. Global AIDS Policy. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey.

Feldman-Savelsberg, Pamela, Flavien T. Ndonko, and Bergis Schmidt-Ehry. 2000. ‘Sterilizing Vaccines or the Politics of the Womb: Retrospective Study of a Rumor in Cameroon’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 14, no. 2: 159–79.

Fenaughty, Andrea M., Dennis G. Fisher, and Henry H. Cagle. 1998. ‘Sex Partners of Alaskan Drug Users: HIV Transmission between White Men and Alaska Native Women’. Women and Health 27, no. 1-2: 87–103. http://doi.org/10.1300/J013v27n01_06.

Ford, Chandra L., Steven P. Wallace, Peter A. Newman, Sung-Jae Lee, and William E. Cunningham. 2013. ‘Belief in AIDS-Related Conspiracy Theories and Mistrust in the Government: Relationship with HIV Testing among At-Risk Older Adults’. The Gerontologist 53, no. 6: 973–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns192.

Gilley, Brian J. 2006. ‘“Snag Bags”: Adapting Condoms to Community Values in American Indian Communities’. Culture, Health, and Sexuality: An International Journal for Research, Intervention, and Care 8, no. 6: 1–12. http://doi.org/10.1080/13691050600891917.

Gilley, Brian J., and M. Keesee. 2007. ‘Linking “White Oppression” and HIV/AIDS in American Indian Etiology: Conspiracy Beliefs among AI MSMs and Their Peers’. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center 14, no. 1: 3–51.

Harding, Susan, and Kathleen Stewart. 2003. ‘Anxieties of Influence: Conspiracy Theory and Therapeutic Culture in Millennial America’. In Transparency and Conspiracy: Ethnographies of Suspicion in the New World Order, edited by Harry G. West, 258–75. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hegel, Georg William Friedrich. 1969. Hegel’s Science of Logic. New York: Humanities Press. Originally published in two volumes, 1812–1816.

Hellinger, Daniel. 2003. ‘Paranoia, Conspiracy and Hegemony in American Politics’. In Transparency and Conspiracy: Ethnographies of Suspicion in the New World Order, edited by Harry G. West, 204–29. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Keeley, Brian L. 1999. ‘Of Conspiracy Theories’. Journal of Philosophy 96, no. 3: 109–26.

Kopelman, Loretta M. 2002. ‘If HIV/AIDS Is Punishment, Who Is Bad?’ Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 27, no. 2: 231–43. https://doi.org/10.1076/jmep.27.2.231.2987.

Metler, Russ, George A. Conway, and Jeanette Stehr-Green. 1991. ‘AIDS Surveillance among American Indians and Alaska Natives’. American Journal of Public Health 81, no. 11: 1469–71.

Mitchell, Christina M., Carol E. Kaufman, and Pathways of Choice and Healthy Ways Project Team. 2002. ‘Structure of HIV Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors among American Indian Young Adults’. AIDS Education and Prevention 14, 401–18.

Morgensen, Scott Lauria. 2011. Spaces between Us: Queer Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Decolonization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Nakai, Anno, Dennis Manuelito, Wesley K. Thomas, William L. Yarber, Robin R. Milhausen, James G. Anderson, and Irene Vernon, eds. 2004. HIV/STD Prevention Guidelines for Native American Communities: American Indians, Alaska Natives, & Native Hawaiians. Bloomington, IN: Rural Center for AIDS/STD Prevention and National Native American AIDS Prevention Center. Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/6788.

Negin, Joel, Clive Aspin, Thomas Gadsden, and Charlotte Reading. 2015. ‘HIV among Indigenous Peoples: A Review of the Literature on HIV-Related Behaviour Since the Beginning of the Epidemic’. AIDS and Behaviour 19, 1720–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1023-0.

Nguyen, Vinh-Kim. 2005. ‘Antiretroviral Globalism, Biopolitics, and Therapeutic Citizenship’. In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics As Anthropological Problems, edited by Aihwa Ong and Stephen J. Collier, 124–44. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Parker, Richard. 2001. ‘Sexuality, Culture, and Power in HIV/AIDS Research’. Annual Reviews of Anthropology 30, 163–79. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.163.

Patton, Cindy. 1990. Inventing AIDS. New York: Routledge.

Patton, Cindy. 2002. Globalizing AIDS. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Pearson, Cynthia R., Karina L. Walters, Jane M. Simoni, Ramona Beltran, and Kimberly M. Nelson. 2013. ‘A Cautionary Tale: Risk Reduction Strategies among Urban American Indian/Alaskan Native Men Who Have Sex with Men’. AIDS Education and Prevention 25, no. 1: 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2013.25.1.25.

Pfeiffer, Elizabeth J., and Harrison M. K. Maithya. 2016. ‘Bewitching Sex Workers, Blaming Wives: HIV/AIDS, Stigma, and the Gender Politics of Panic in Western Kenya’. Global Public Health, published online 2 September. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1215484.

Ramirez, Juan R., William D. Crano, Ryan Quist, Michael Burgoon, Eusebio M. Alvaro, and Joseph Grandpre. 2002. ‘Effects of Fatalism and Family Communication on HIV/AIDS Awareness Variations in Native American and Anglo Parents and Children’. AIDS Education and Prevention 14, no. 1: 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.14.1.29.24332.

Romero-Daza, Nancy, Margaret Weeks, and Merrill Singer. 2003. ‘“Nobody Gives a Damn If I Live or Die”: Violence, Drugs, and Street-Level Prostitution in Inner-City Hartford, Connecticut’. Medical Anthropology 22, 233–59. http://doi.org/10.1080/01459740306770.

Roscoe, Will. 1998. Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Ross, Michael W., E. James Essien, and Isabel Torres. 2006. ‘Conspiracy Beliefs about the Origin of AIDS in Four Racial/Ethnic Groups’. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 41, no. 3: 342–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qai.0000209897.59384.52.

Sangaramoorthy, Thurka. 2014. Treating AIDS: Politics of Difference, Paradox of Prevention. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Schoepf, Brooke Grundfest. 1988. ‘Women, AIDS, and Economic Crisis in Central Africa’. Canadian Journal of African Studies 22, 3: 625–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/485959.

Scott, James C. 1987. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sears, James T. 2002. ‘Out of Harmony on the Cherokee Boundary: Clinics, Culture and the Sex Ed Curriculum’. Sex Education 2, 155–68. http://doi.org/10.1080/14681810220144909.

Setel, Philip W. 1999. A Plague of Paradoxes: AIDS, Culture, and Demography in Northern Tanzania. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Simpsen, Audra. 2016. ‘Afterward: Wither the Settler Colonialism?’ in Settler Colonial Studies 6, no. 4: 1–8.

Taussig, Michael T. 1980. The Devil and Commodity Fetishism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Vernon, Irene S. 2000. ‘Facts and Myths of AIDS and American Indian Women’. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 24, no. 3: 93–110. https://doi.org/10.17953/aicr.24.3.a08g7n6h1804mp5p.

Vernon, Irene S. 2001. Killing Us Quietly: American Indians and HIV/AIDS. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Vernon, Irene S., and Roe Bubar. 2001. ‘Child Sexual Abuse and HIV/AIDS in Indian Country’. Wicazo Sa Review 16, no. 1: 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1353/wic.2001.0015.

Walters, Karina L., Ramona Beltran, and Tessa Evans-Campbell. 2012. ‘Keeping Our Hearts from Touching the Ground: HIV/AIDS in American Indiana and Alaska Indian Women’. Women’s Health Issues 21, no. S6: S261–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2011.08.005.

Walters, Karina L., and Jane M. Simoni. 2009. ‘Decolonizing Strategies for Mentoring American Indiana and Alaska Natives in HIV and Mental Health Research’. American Journal of Public Health 99, no. S1: S71–76. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.136127.

Weaver, Hilary N. 1999. ‘Through Indigenous Eyes: American Indians and the HIV Epidemic’. Health and Social Work 24, no. 1: 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/24.1.27.

Endnotes

1 Back

Preferred terminologies used by indigenous populations to refer to themselves in the United States vary widely, in this paper we primarily use the term ‘American Indians’, but occasionally use the terms ‘Native Indians’, ‘Native Americans’, and ‘Natives’ interchangeably.

2 Back

‘White’ is broadly understood in American Indian contexts to mean anything deemed non-Native and deriving from European American culture, colonialism, and socioeconomic privilege.