The program is perfect

Narcotics Anonymous and the managing of the American addict

—

Abstract

Introduction

Narcotics Anonymous (NA) is a spiritual program committed to helping self-identified addicts get and stay sober. While historically derived from and in many ways similar to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), notably in its recovery ideology and the use of a Twelve Step program, NA presents itself as an open-ended approach to addiction and the psychoactive substances that can inspire such a condition. ‘Jimmy K.’ (James Kinnon) is widely credited with founding NA in California’s San Fernando Valley in 1953, after attending AA meetings and encountering other addicts who also struggled with alcohol and other drug use (Peyrot 1985, 1511; Snyder and Fessler 2014, 442). Initially NA battled for legitimacy, largely because the substances members were trying to avoid using were classified as illicit. This classification attracted aggressive police surveillance and drove early meetings underground (Narcotics Anonymous World Services [NAWS] 1998). Today NA asserts that it is one of the world’s fastest-growing recovery organizations, with more than 63,000 weekly meetings in 132 countries; some NA members regard this expansion as evidence of the superiority of NA’s program in prioritizing recovery from addiction, no matter the substance, over AA’s narrow focus on a single substance (NAWS 2014). [note 1]

In this article I look at NA membership from two converging vantage points. I examine how blame for failure is shifted from the organizational program onto the individual addict, and how this process fits with larger NA discourses related to individual responsibility. My contention is that these discourses illustrate the influence of a neoliberal understanding of the life course that has taken root among ‘clean’ NA members. I argue that the embrace of a neoliberal framework should be understood in relation to the parallel reduction of the social safety net in the United States to a ‘bare minimum in favor of a system that emphasizes personal responsibility’ (Harvey 2005, 76) [note 2] . Such discourses and accompanying social trends align neatly with NA’s espoused ideology about living according to organizational dictates. Addiction is understood by NA members as an incurable lifelong disease, treatable only through individual vigilance, meeting participation, and constant recognition that the cause of addicted behavior resides in the individual. As Reith (2004, 293) writes, this assumes an ‘essential identity that is stable and unchanging; based on an incurable disease and defined by a complete and irreversible loss of control’. I argue that NA’s methodology and ideology fail to account for individual circumstance and thus conflate success in recovery with economic self-sufficiency and independence. In this vein, I treat NA as a ‘therapeutic mode of self-understanding’ that functions ‘as a form of false consciousness that translates political collective problems into psychological individual predicaments, thus inhibiting the possibility of genuine structural change’ (Illouz 2008, 106). To live ‘clean’ as an NA member is to simultaneously acknowledge the absence of control over substance use and to shape oneself as an economically productive and self-responsible citizen. An unwillingness or inability to integrate these program tenets into one’s life becomes not only a failure to confront problematic narcotic use but a rejection of the mores governing contemporary life, notably its demands for individual and economic self-sufficiency regardless of circumstance. These factors, compounded by the widespread influence of NA’s Twelve Step approach to defining and treating addiction, constrain to a problematically narrow range the available pathways for addicts seeking help.

It is important to note that as NA traces its origin to 1953, it predates the rise of neoliberalism as a globally pervasive ideological force in the 1980s (Harvey 2005, 13). In this sense then, NA is a forerunner to the growth of pervasive neoliberal subjectivities; here, I wish to emphasize how neoliberalism has become ‘hegemonic as a mode of discourse’ (Harvey 2007, 23). My focus is on how neoliberalism has ‘pervasive effects on ways of thought and political-economic practices to the point where it has become incorporated into the commonsense way we interpret, live in, and understand the world’ (ibid.). The intertwining of NA with a neoliberal worldview during the organization’s period of significant growth in the 1980s and 1990s is important because it reflects the ascendancy of an ideologically rigid and individual-centered approach to addiction and recovery (NAWS 1997; NA Ireland [[3]] ). NA’s growth paralleled an increased reliance by criminal justice systems throughout the United States on a disease-based model of addiction as a component of punishment and sentencing (Burns and Peyrot 2003, 417; Tiger 2013, 82), a burgeoning ‘cultural trope of individual responsibility’ around conceptions of care and treatment (Wacquant 2009, 307), and a devotion to economic productivity as a measure of individual worth. The link between the sway of neoliberalism and NA’s rise as a major arbiter of how recovery from addiction should be approached and understood is thus evident in the organization’s ideological foundation. NA’s ideological view of success in recovery fits with a neoliberal worldview that purports to champion individual freedom and personal responsibility yet insidiously destroys opportunities for collective optimism and purpose that could shield vulnerable populations from destructive drug use (Alexander 2010, 12).

Consequently, I contend that NA’s organizational growth can in part be attributed to the state’s withdrawal from providing addiction-relevant services, as well as the decline of ‘meaningful work’ in America and the growing uncertainty that structures the lives of many members prior to and during their path to sobriety (Garcia 2010, 187; Wacquant 2009, 54–55). [note 3] NA’s program requires ‘taking responsibility’ for one’s actions, while also making individual declarations that one cannot control their narcotic use and must turn themselves over ‘to the care of God, as we understand him’, in order to stay clean (NAWS 1998, emphasis in original). To this end I build upon a well-established scholarly tradition that critiques the ‘gross oversimplification involved in seeing self-awareness as a comprehensive solution’ to addiction-related problems and struggles (Schur 1976, 174). Because NA requires ‘taking responsibility’ – while being simultaneously a stabilizing force and explanatory model for past individual hardships and suffering linked to drug use – it demands that its members fully internalize failures and setbacks as entirely their own, divorced from circumstance. In arguing that NA promotes a specific view of success that aligns with neoliberal values of individual economic self-sufficiency regardless of circumstance or setting, I aim to draw attention to how recovery treatment programs propagate and insulate narrow interpretations of addiction that then legitimate wider behaviors and norms that are neglectful of addiction’s contextual influences. In short, I examine how NA’s treatment program comes to confirm a viewpoint compliant with a neoliberal outlook that roots successful recovery in the convictions of self-responsibility and economic productivity frequently invoked by NA members (Prussing 2008, 360; Tiger 2013, 36).

NA structures recovery in a way that makes any failure to get or stay ‘clean’ the fault of the individual addict, insulating the organization’s recovery program from criticism. William, one of the addicts I met who has now ‘been clean’ more than twenty years, spoke at length on what he regards as NA’s ‘perfect’ program, emphasizing that any failures and relapses are entirely the addict’s fault and rooted in their inability to hear and follow the outlined recovery steps. [note 4] ‘You know who it doesn’t reach?’ William asserted. ‘The addict that don’t want to be reached. But even that addict, it will work for any addict’. While it must be emphasized that NA has brought stability and salvation to the lives of many addicts, the difficulty of casting criticism or doubt on the recovery program – ‘it will work for any addict’ – limits its reach and effectiveness. NA’s approach to recovery is fundamentally centered on personal responsibility and individual improvement, with no room or concession for systemic, institutional, or societal factors contributing to narcotic use and addiction. This displaces the struggles and failures of vulnerable communities onto individual addicts as entirely their own, hereby thwarting inquiry into the causes and motivations for addiction and narcotic use in contemporary America. Simply stated, treatment and understanding of addiction, particularly the circumstantial factors that contribute to its development and persistence, cannot advance without recognizing how NA structures recovery in specific and consequential ways.

Methodology

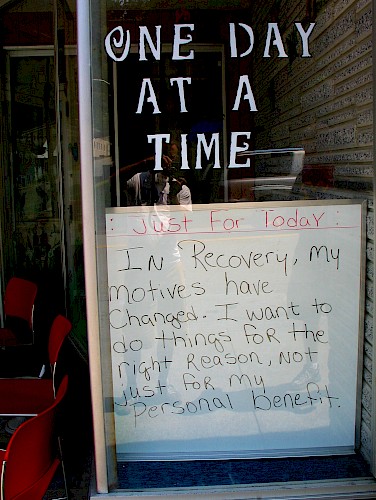

Fieldwork for this article was conducted in a small city (population less than fifty thousand) in the northeastern United States. Nine NA members (eight men and one woman) were interviewed for approximately one hour and three of the nine gave extensive commentary over several interviews. All interviewees were over forty years of age and had been active in NA for at least five years. The interviews were semistructured in format, and interviewees were encouraged to digress from my questions as they wished. In keeping with the established practices of anthropology and the privileging of anonymity in NA, all names that appear here are pseudonyms and the name of the city where fieldwork took place is withheld (Campbell and Lassiter 2014, 40). I have chosen to focus heavily on the extensive interviews I did with three NA members (William, Allen, and Peter) over several sessions. This approach allowed me to trace more detailed life histories, including their years as active addicts and those now in recovery, while charting a clear progression of thought and internalization of NA’s ideology and its role in shaping individual lives. I also conducted six months of participant observation at a local ‘Recovery Cafe’, spending approximately two hours each week in the cafe during this time. The Recovery Cafe is a space for addicts, many of them newly sober and in the early stages of trying to live ‘in recovery’, to congregate and draw strength from others with similar experiences.

Additionally, the city where fieldwork took place is a noteworthy backdrop to the lives of the addicts introduced below, as it has followed a sadly familiar historical trajectory. The city lost nearly half its population from a peak of more than one hundred thousand residents in the 1950s, as major industries that grew a post-World War II manufacturing middle class either left in search of reduced labor costs abroad or simply ceased operation (Broughton 2014; Kenneally n.d.; Maharidge 2013). The result is a city and surrounding area pockmarked with blight and despair. Large, mostly brick, buildings that were once imposing and impressive now stand empty and in varying stages of decay. An endless proliferation of strip malls and chain stores offering low-paying retail work tries to hide but does not fully conceal these scars on the landscape. It is in this lived landscape of the ‘other America’ – the one found in places that used to have a plant or factory as the primary employer but now have a WalMart Supercenter – that NA resonates with larger cultural shifts and tendencies proselytizing a neoliberal view of the self (Stewart 1996, 4). This is a landscape rampant with narcotic use, sometimes as a means to prolong the workday and strive for financial independence, yet where the ideological dictates of recovery categorically ignore the abundance of circumstantially rooted anguish (Garriott 2011; Pine 2007, 361).

This is not to say that the decline and erosion of meaningful work with a meaningful paycheck is solely the cause of destructive narcotic use and addiction in this neglected slice of America. Instead, my aim is to make explicit the ways in which NA members internalize their addiction and recovery, framing talk of their struggles in a language of personal responsibility and individual struggle, despite a decline in treatment options and facilities, and a lack of access to basic health care or an economically viable existence (Bourgois and Schonberg 2009, 149). NA members are conditioned to link their sobriety to capitalistic productivity, regardless of contradictory cultural and economic realities in the lived environment. NA thus illustrates contemporary America’s production of citizens ‘whose moral autonomy is measured by their capacity for “self-care”, their ability to provide for their own needs and service their own ambitions’ no matter the other factors shaping their lives (Brown 2006, 694).

I draw from extended interviews with William, Allen, and Peter to illustrate how these personally destructive processes are rooted in ideological shifts structuring the nature of governance and responsibility. Each of them exhibit the traits of a ‘true believer’, as they fully embrace the ‘premises of programming, adopting the language of recovery and responsibility’ into how they understand and publicly present themselves (Moore and Hirai 2014, 6). William and Allen have both been clean more than twenty years and are highly active in NA throughout the region. William is also Allen’s sponsor, an important NA relationship entered into when both members feel they have supportive guidance to offer the other that extends beyond the context of the meeting. William is black, in his early fifties, and has lived all of his life in the local area. He starting using drugs in high school, ‘dibbling and dabbling’ with anything he or his friends could get their hands on, most often alcohol and marijuana, less frequently crack cocaine and prescription medication. Allen is white, a few years younger than William, and also grew up in the area. He told me he began using drugs much earlier, at seven or eight, ‘stealing beers and other drinks at home when no one was looking’ and by twelve he was ‘drinking in bars with [his] mom’. He moved away for a while, bouncing from New York City to Florida and then Texas before returning to the area almost a decade ago. Allen says he ‘tried every drug [he] could get’, adding that cigarettes are the only addiction he has not yet been able to break from. Finally, Peter is white, in his late fifties, and a well-known regular at the Recovery Cafe. He was a special education teacher at a local middle school until he was fired for using crystal methamphetamine between classes. Peter likes to say he came to addiction late, as he didn’t start using heavily until his mid-twenties, but made up for the lost time with aggressive use of a broad array of drugs. He grew up in the local area and draws tremendous joy from helping the newly sober navigate their early efforts with NA’s program.

NA, the Twelve Steps, and recovery

NA is ‘woefully understudied’, particularly when compared to the literature devoted to AA and its recovery program (Snyder and Fessler 2014, 441). Importantly, this imbalance highlights the power and pervasive influence of AA’s recovery ideology across the American addiction landscape. As some of the existing literature notes, AA’s organizational structure conferred institutional stability to NA, and offshoot narcotics recovery programs that aspired to greater independence have struggled (Snyder and Fessler 2014, 442). A persistent focus then in the anthropological scholarship concerned with AA and NA considers the role and potential limitations of organizational ideology, notably the Twelve Steps and how this program is viewed and understood in varying cultural and religious contexts (Brandes 2002; Cain 1991; Hoffmann 2006; Jensen 2000; Pine 2008; Wilcox 1998). Of relevance here is how NA’s recovery ideology engenders particular views of individual responsibility that ‘target the inner self of the subject’ and draw strength from prevailing societal views of conduct and self-care (Carr 2011; Garriott and Raikhel 2015, 483). My research joins a growing body of scholarship focused on addiction recovery within ‘broader concerns about desire, freedom, choice, and constraint under conditions of neoliberalism’ (Garriott and Raikhel 2015, 483; see also Hackett 2013; Reith 2004; Seddon 2007). In an era of neoliberalism, addiction is framed as a failure of individual users to ‘exercise properly their freedom to choose’ (Seddon 2007, 339). The focus of NA’s recovery logic is ‘reshaping’ individual subjectivities to fit the expectations of life within the context of neoliberalism (Reith 2004, 297). Success in one’s recovery from addiction, framed in AA and NA as a reassertion of a loss of control over one’s existence, becomes the lens by which individuals measure themselves. The result is a treatment methodology for addiction organized by ‘market rationality’, which equates success with responsibility and economic output, leaving little room for questions of opportunity, access, discrimination, or circumstantial limitations (Brown 2006, 694).

The title of this article comes from William’s assertion that NA’s recovery program is ‘perfect’ and ‘divinely’ inspired. Like William, many members regard the program as above criticism or amendable in any way. Such a view fits with a long known therapeutic group tendency to ‘see their scheme as the unquestionable answer to all addiction problems’ (Schur 1976, 172; emphasis in original). My argument builds from William’s statement to contend that NA manages addicts as group members by extolling self-sufficiency, economic productivity, and independence as signs of successfully living ‘in recovery’. As Peyrot (1985, 1514) writes, ‘the ultimate goal of NA is the transformation of an “addict” into the type of person who does not use drugs’ (italics in original). Through participation in group meetings and working the Twelve Steps, individual members see their ‘own life events in terms of the NA world view, thereby therapizing’ themselves (Peyrot 1985, 1516). This construction of recovery is problematic because it ignores the contextual realities facing many group members, realities shaped by an aggressive turn toward neoliberal governance in the United States that while purporting to champion individual rights, delegitimates the notion that contextual circumstances can contribute to drug use and addiction. NA members assert a singular recovery path as the only viable option, and the ideology underwriting the program systematically blinds members to persistent socioeconomic inequalities, and thereby fosters a lived environment rich with temptation, addiction, and persistent individual despair.

Sobriety among decay

Unsure of how long the drive would take and not wanting to be late, I arrived almost forty minutes early for an interview with Allen at his home. Sitting in my car parked along a major street not far from the city’s downtown, I looked over my notes and waited for our agreed 2:30 pm meeting time. While waiting, I watched the events of the day unfold on the sidewalks around me. Across the street was a large Dollar General store where customers were gathered smoking cigarettes, sending text messages, and chatting. Children ran happily along the sidewalk and groups of teenagers from the nearby high school flirted with one another as they left school. The Dollar General’s building was in disrepair and sat next to a vacant lot overgrown with weeds and strewn with rusting shopping carts, litter from fast-food restaurants down the block, and empty beer cans. Along the side of the street where I was parked were several homes in varying states of decay. Two were condemned with prominent yet fading posters reading ‘WARNING – THIS BUILDING IS UNSAFE’; between them was a family home whose front steps were filled with potted plants, shoes, and other trappings of daily life.

This landscape is scarred, and scattered among the distress are signs of life, struggles, hope, and despair. Allen’s home is two doors down from a condemned building. Once a large family home, the building is now subdivided into four apartments. He shares a first floor apartment with his girlfriend and her adolescent son. We enter the apartment directly into a cluttered kitchen where nearly every available space on the countertops and shelves is stacked with cups, plates, cookware, and innumerable boxes of cereal, crackers, and other snacks. Allen hunts for a clean cup and asks what I want to drink, running through several choices of soda. Everywhere there are ashtrays full of cigarette butts, yet Allen says we should talk outside so he can smoke.

We pass through the shared basement, crowded with decrepit bicycles and half-used construction supplies, and then into the backyard. As we sit down to begin the interview he continues to talk about the house. He explains that he moved in with his girlfriend recently after a fire destroyed the house he was previously living in, exclaiming, ‘I’m still paying bills on a house that burned down! Can you believe that?!’ Shortly after Allen moved in, the current house flooded when a nearby river, swollen from heavy rains, spilled into the basement. While the initial flood damage had been cleaned up, a persistent dampness remains and Allen says he’s now dealing with mold and is concerned for everyone’s health. While we continue to chat it begins to rain and we are forced to retreat back inside and settle in the living room. I sit in a chair at Allen’s desk – ‘my office’, he jokingly declares – while he takes a seat on an aging loveseat, finding a mostly empty ashtray and putting it on the floor at his feet.

Poverty and precarity surround Allen and his family. He has a variety of current jobs that include doing ‘some stuff on the internet’ and several hours each month helping a friend who does construction, but none of it is stable or comes with health insurance or other benefits. His girlfriend works full time but at a rate only slightly above minimum wage and also without any additional benefits. Like those in Wacquant’s (2015, 264) study, their lives are comprehensively marked by ‘rampant economic instability and abiding social insecurity’. Yet what is noteworthy about Allen, and many others in NA, is their deep internalization of an outlook on life that simultaneously denigrates and champions the individual under a logic of persistent self-responsibility. Allen, William, and Peter, as well as countless other group members, are alive today because of NA. Without it, all say with unflinching candor, they would have overdosed and died years ago. Yet they and the rest of the organization’s members must also live within NA’s totalizing institutional logic. Paradoxically then, they must comprehensively embrace self-responsibility and dismiss circumstantial context as irrelevant to their struggles with addiction.

Talking about ‘using’

What follows is a detailed account of how William and Allen talk about their past narcotics use. Of importance is the way in which NA’s recovery program structures how they remember and talk about their past drug use. Carr (2011, 11) notes that ‘a particular way of speaking’ about addiction and recovery in the United States is one of the principle measures of individual success as a sobriety group member. Following Carr’s assertion that mainstream American addiction treatment is a ‘particularly illuminating site’ that reveals ‘dominant cultural values’, I examine how William, Allen, Peter, and other NA members use talk of their past drug use to illustrate their transformation into economically productive, honest, and trustworthy citizens, members of the mainstream and holders of dominant cultural values (ibid., 22). Through talk, members confirm NA’s recovery program and the framing of addiction as an incurable disease that is solely treatable by following the organizational steps. It is thus a therapeutic process that illustrates how ‘specific geographies of addiction intersect with institutional and historical formations to shape the lives of addicts’, systematically hindering efforts to harness change or challenge this methodology (Garcia 2010, 9). Put differently, prevailing forms of addiction treatment are shaped by views dismissive of connections to systemic structures of exclusions, suffering, violence, or denial that mark life for many Americans within a neoliberal context.

William, as noted above, began regularly using drugs in high school. Prior to this he occasionally drank alcohol and smoked marijuana, starting at ‘around eleven or twelve’, but his consistent drug use started at sixteen. ‘I somehow managed to finish high school’, William added, and he continued to use heavily in college, dropping out during his first year. This was the early 1980s and after dropping out William found himself stuck in addiction’s vicious cycle, wanting to quit using but having few options for help with this process beyond a supportive and sympathetic mother. With her help he cycled through several treatment programs and sporadic meeting attendance, primarily at AA meetings since access to NA was limited in his area at the time. Throughout this chaotic period of life, William continued his heavy narcotic use.

William also spent several years in jail during the 1980s, an experience he was unwilling to talk about in detail but one he credits with allowing him to finally ‘hear the message’ of NA. After being released, he started to regularly attend meetings and eventually got clean. To quote William at length:

I was tired, I was done. The message that I had heard ten years earlier was the same message, it was like that saying, ‘When the student is ready the teacher will appear’, and I was now ready. And that’s what it’s all about, opening yourself and becoming pliable. Be able to be told something and not think you have all the answers. Being able to listen as much as you talk. Because that’s what most of us who come in the program [do], a lot of talking and no listening.

Being able to hear the message of NA and engage with a recovery program he now regards as ‘perfect’ – in his view, the only solution to both his disease and feelings of ‘dis-ease’ – was made possible because of the patterns that first motivated his substance use. For William, a sense of dis-ease as a high school student was rooted not in moments of peer pressure to use drugs but rather a pursuit of peer acceptance. William saw using and selling drugs as crucial to maintaining the acceptance and friendship of his classmates, as well as a means to manipulate other students into posing as his friends. This gave William a power he used to mask feelings of discomfort. William had easy access to drugs, as his father and other family members consistently had alcohol, prescription medication, and marijuana in their houses. Stealing these substances exacerbated his feelings of dis-ease and drove him to use with greater frequency and intensity, while he also coerced others into doing the same. He crafted the persona of a tough, menacing bully who always had something others wanted in order to push aside his own feelings of vulnerability and dis-ease, which only propelled heavier drug use and eventual addiction.

William now looks back on this past drug use through an unambiguous and ideologically structured set of interpretive glasses that take NA’s recovery program as a sacred guide to living clean. When I asked him where addiction resides (Is it in the individual or do other things contribute to its manifestation?), William was unequivocal in his response: ‘Definitely individual. Some manage their recovery in stressful situations that others would fail in. But, if you expose yourself, we like to say, “it’s [narcotics] more powerful than anything else around”. Because it waits. The disease is patient. It will stay dormant. But the minute you have too much, it comes right back to the surface again’. In this short exchange William makes several statements that demand to be looked at in detail. He first clearly demarcates how he sees the boundaries of addiction. William’s position, ‘definitely individual’, reflects NA’s views, which are dismissive of auxiliary factors and circumstances in evaluating addiction. For William these auxiliary factors could include his consistent and easy access to alcohol, marijuana, prescription pills, and sometimes cocaine from an early age, alongside limited and disinterested supervision from adult relatives. Finally, William gives addiction agency: it is a ‘patient disease’ that lies in wait for a moment of individual weakness. [note 5] In NA’s structure, addiction demands constant individual vigilance and management of the self, no matter the setting or circumstance. Such a rendering confirms NA’s institutional view of how treatment and recovery should unfold, while also creating an explanatory model of narcotic use that requires individual admission, acceptance, and awareness of addiction along specific ideological lines.

What this way of talking about ‘using’ leaves out is worth considering, as it illustrates how ‘American addiction therapeutics’ are ‘firmly rooted in cultural ideologies of language that one can hardly imagine an alternative’ (Carr 2013, 174). This is evident in NA’s recovery model, which does not consider how social, economic, or educational circumstances influence getting and staying clean. Individual context is largely irrelevant within NA’s recovery structure and any failures to achieve or maintain sobriety are, at their core, understood as the fault of the individual. Such a perspective is hardly new. Schur (1976, 172), working on individual self-absorption in the 1970s, argues that ‘methods for voluntary treatment of the already addicted affect neither the root cause of turning to addictive drugs, nor the secondary aspects of the addiction situation we have fostered through our repressive drug policies’. William’s statements on using drugs reflect how success in NA is filtered through a comprehensive internalization of organizational logics championing the supremacy of ‘self-responsibility’ while neglecting acknowledgement of ‘human interdependency’ or mitigating context (Han 2012, 28). While this internalization has brought stability to William’s life, its position as one of the widely recognized mechanisms for recovery from addiction in American life abandons those struggling with narcotic use and unable to derive meaning from organizational logics.

Born in the early 1960s, Allen started drinking alcohol he took from adults in his home ‘at seven or eight’. Even prior to this he was regularly given small amounts of whiskey in his baby bottle to stop his crying and induce sleep. From a young age Allen was often left alone in a home marred by consistent violence, and he had easy access to a wide range of narcotics. Raised by a single mother, he remembers a steady procession of boyfriends and domestic violence coupled with alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs. Adding to the despair, Allen’s older sister was murdered when he was four, and, while he does not talk about it, it is the moment he marks as the beginning of his life going ‘downhill’. By the time he was twelve the local bar would frequently call his home to have him come pick up his drunk and unconscious mother. Allen would drive to get her but he often ended up staying and getting drunk himself, to the amusement of the regulars who bought his beers. Allen added that adolescence was also the moment when his drug use expanded to ‘anything and everything’ he could get. Describing himself as a ‘junk head’ during his teenage years, he was also quick to emphasize the individuality of addiction – how his experiences with drugs were entirely his own – just as he is now ultimately responsible for his recovery. Yet throughout his early life drug use and addiction constantly enveloped him as expected, even encouraged, behavior.

Allen left home at sixteen and continued heavy drug use until he was twenty-one. Looking back on these years as a now long-tenured NA member, Allen said ‘I started [my life] in hell… . In some way or another when I came into NA, I [had] a criminal mentality… . I hated everyone in society, because of how I grew up. My whole purpose was just to destroy’. By twenty, Allen says he saw his drug use as a problem but felt unable to stop. At this time he was doing a lot of ‘freebase’, which he described as ‘the same thing as crack, you just make it yourself’. [note 6] He added, ‘within six months I lost everything I had. I was nothing. I went from like 180 [pounds], the weight I am now, to like 135’. Allen is of average height, a few inches under six feet, and at 180 pounds is trim and healthy. As we talked I struggled to picture him more than forty pounds lighter, no doubt gaunt and emaciated, from nearly constant drug use. Picking up on my struggles to visualize this bodily harm, Allen smiled dryly and added that food was rarely something he thought of or sought out during this period of use. Yet like William, Allen does not make a substantive link between ‘how [he] grew up’ and his struggles with addiction. Instead he compartmentalizes his childhood memories as something that shaped him into a young adult who ‘hated everyone’, while his addiction is a disease entirely his own that, he believes, would have manifested no matter the circumstance.

In the six months before he joined NA, freebasing crack cocaine caused Allen to forget or forego eating, and it left him unsure of where he was, waking up in places he did not recognize and not remembering what city he was in. Allen’s story exemplifies ‘hitting bottom’, the moment of abject despair NA presents as necessary for addicts to acknowledge the overpowering grip of their addiction and seek help. It is also an account that references a life of tragedy and despair – including his sister’s murder, and his adolescent drinking ignored or treated as normal behavior – but still dismisses the impact of such experiences on the individual. To make his story of using fit with prevailing recovery program paradigms, he roots his struggles with drugs within himself, as a disease he is powerless alone to overcome. Allen, William, and others at NA are taught to give limited credence to what Garcia (2010, 9) describes as the ‘broader moral worlds’ of addiction, how ‘institutional and historical formations … shape the lives of addicts’. Instead, addiction is framed as a lifelong disease best managed with individual vigilance, prayer, and the resumption of economic productivity.

How Allen and William talk about using narcotics highlights an inherent structural issue with NA membership as the basis for addiction recovery. NA conditions individuals to understand themselves as flawed and broken, and the recovery program as the only path to recovery and redemption. Such a framework leaves little room to consider how individual circumstance potentially contributes to one’s addiction. While these circumstantial factors are discussed – Allen’s violently unstable home life or William’s easy access to drugs – the cause of addiction is the flawed and sick biology of individual addicts. Further, addiction can only be overcome by ‘working the program’, one that demands tremendous individual re-evaluation and reflection, as well as conformity to an economically successful status quo regardless of its feasibility. In the next section I address how this notion of addiction influences life after addicting substances have been removed from the addict’s body.

Talking about ‘living clean’

When NA members talk about ‘living clean’ (without addicting substances in their bodies), they are talking about the management of self along a specific set of guidelines. ‘Working the program’ in NA is typically structured as active engagement with the Twelve Steps, consistent meeting participation, and an ongoing relationship with a sponsor. Additionally, all of these program components revolve around notions of spirituality and the central place this concept occupies in the structuring of recovery. It is thus a set of practices embedded within the intersubjectivity of member subjects that finds firmest root in the individual and the necessity for self-responsibility. [note 7] Successful recovery in NA demands constant vigilance; as William noted earlier, ‘some manage their recovery in stressful situations that others would fail in’. What’s important about his comment is the recognition that failure is not uncommon among those trying to use NA to overcome their addiction; underlying this recognition is the premise that when failure occurs it is because the individual did not sufficiently manage and monitor their actions. In granting agency to addiction – an ability to engage in treachery and deceit – William is arguing for the infallibility of NA’s program and the necessity of constant individual management of one’s addiction. He further conflates success in this process with an assertion of personal and economic self-sufficiency.

When I asked William how the Twelve Steps serve as a guide for living, he immediately replied that they ‘helped to “right size” me. They’ve helped me to know my place’. Living clean in NA means following a ‘strongly moral logic according to which autonomous individuals are responsible for themselves’ (Schüll 2012, 267). Following this logic requires making the individual the focus of attention, and molding success in recovery as not only living clean but also, returning to William’s words, ‘being a good employee [and having] stability in the community’. Yet this again raises the persistent concern of how NA, as a widespread method for treating addiction in the United States, also structures how addiction is popularly understood in specific and consequential ways. If successful recovery in NA is premised in part on individual responsibility, both for one’s past actions and current sobriety, then the daily reality faced by members becomes, at best, a secondary concern. At worst, it is neglected altogether as having little bearing on an addict’s chances of realizing sustained sobriety. This makes it a view with powerful reach, scope, and consequence that makes ‘being a good employee’ one of the measures of individual worth and success, and inflicts this uncompromising ideology on a population frequently marked by moments of extreme suffering, marginalization, and interpersonal anguish (NAWS 2006, 9).

Allen spoke of life after starting to attend meetings and beginning to get clean in similar ways. Taking a more general focus than William, he said that ‘for a lot of people who didn’t come in [to meetings] with the functioning skills of a normal human being, a productive member of society, it [NA’s program] gives you that skill set to live a good life without getting in trouble’. Allen’s conflating of normalcy with economic productivity in NA is revealing, pointing to the assumption that opportunities for economic independence are prevalent. They are the same skills Rose (2000, 327) bundles to form ‘circuits of civility’, wherein ‘particular types of control over [individual] conduct’ are enacted and maintained. It is a conflation along NA’s specific ideological lines that limits how addiction and successful attempts at recovery from this affliction are broadly understood and enforced. The unaddressed yet equally problematic concern of why individuals who find themselves in need of NA also lack the ‘skill set to live a good life’ is rarely considered. The focus in NA is not on why and how the person entering a meeting had not previously obtained the skills of a ‘productive member of society’. Instead, the factors that brought about this condition are secondary to molding the individual into someone who assumes total responsibility for the things they have done in the past, while professing powerlessness over their ability to self-regulate, in order to then become a productive and clean member of society, no matter the challenges they face moving forward.

Becoming an NA member means adhering to a tight circle of logic that allows individuals to make sense of often horrific past experiences and actions without considering how context made such actions a likely inevitability. NA positions members in what Roberts (2014) calls ‘infrastructures of individualism, the unseen endoskeleton of support that allows first-worlders a feeling of independence from the other people around them’. While support is a major part of NA’s vitality, it is also rigid, limiting, and through a particular form of enacted self-discipline, the extent to which new forms of treatment and understandings of addiction are possible. NA helps members forgive themselves for the horrible things they may have done, but the cost of that forgiveness is adherence to an ideology that makes it impossible to consider the circumstance that brought them to such a place, to ask about what contributed to wanting to be constantly high, unable to conceive of doing anything else, and willing to do awful things in order to realize this state of being. Twelve Step approaches are ‘the foundation of most professional training programs and treatment centers for addiction in the United States’ and many of these centers frame addiction as a chronic brain disease (Prussing 2008, 360). [note 8] Yet addiction is also a condition in which human suffering is a contributing factor, and drug use – at least initially – an attempt to momentarily soothe or block individual anguish and pain. To not see this suffering as at least in some way linked to circumstance, to systematically deny that there are contributing factors – as NA logic does – is shamefully callous, an example of neoliberalism’s caustic ideology of ‘moral individualism’ (Wacquant 2009, 81).

Peter’s talk of ‘living clean’ focused on addressing individual ‘defects’. We met for an interview on an unusually warm day in early December at the Recovery Cafe. Nearly sixty, Peter has been clean and in NA for sixteen years. Prior to joining the organization he was a special education teacher at a middle school but was fired when he began using drugs at work. Like William and Allen, Peter started using early in life, estimating that he first smoked marijuana in eighth grade. As noted earlier, Peter went several years without using drugs during high school and college, before escalating to heavy drug use in his late thirties and early forties. In addition to smoking marijuana he did a range of psychedelic drugs and cocaine, and finally began using crystal methamphetamine, which he described as a ‘superman pill’ that gave him tremendous bursts of energy. Such bursts, however, could be unfocused, as he recalled being able to ‘spend hours folding a grocery bag’ while high on meth.

As we talked, Peter kept returning to the individual as the foci of struggles with addiction. ‘Drugs and alcohol are not really the problem, it’s us [addicts]’, he stated bluntly. He carried tremendous resentment towards himself as well as ‘others – institutions, God’ into his first meetings and efforts at living clean, and said he sees many new members doing the same. For Peter, addiction is ‘something you have in your make-up’. In other words, addiction is an inherent presence that is the only relevant factor linking NA’s otherwise diverse fellowship. To illustrate the scope of this view, Peter added that ‘you can be an addict without using. You either are or are not an addict – it’s something you have in you’. For Peter, whether one uses drugs is secondary, and even unnecessary; addiction is all that matters and the only way to stay clean is to individually accept one’s powerlessness over addiction and, in his paraphrasing of Step Seven, to ‘ask God to humbly remove it’ from your life. Peter added that this totalizing view of addiction and recovery, and how one lives clean, comes directly from AA’s Twelve Steps. In Peter’s words, it is a ‘divinely inspired’ program, the work of God speaking through AA’s cofounder Bill Wilson. Much like how William spoke of the recovery program as ‘perfect’, Peter sees divine inspiration at the core of NA’s recovery steps that is in turn the source of its powerful ability to inspire members to live clean.

As Peter and I talked, a young man looked repeatedly at our table from across the room. After several minutes the young man got up from his chair and walked towards us, pausing several times and pacing nervously as he crossed the room. Mustering his courage, he first apologized for interrupting and then took Peter’s hand. ‘I want to thank you’, he said, his voice cracking with emotion. He added that he was still clean after several days and had been ‘laying and praying’, avoiding temptation and seeking guidance from his Higher Power, and Peter’s recent words of guidance and encouragement were critical in this regard. They embraced and the young man returned to his table. While this brief and emotional moment captures the strength of NA as a recovery tool, it obscures the contextual factors that can contribute to addiction. For this young man, NA provided a refuge from a desperate life of anguish, and it gave him the tools and the inspiration to reverse what had felt like an intractable existence as an addict. NA allowed him to share with others in a program that inspires deep, emotionally sustaining bonds between individuals. Yet NA must also fill a lonely void in the absence of other options for a meaningful existence, necessitating a totalizing ideology that asks members to bend their lived reality to the dictates of the organization and its approach to confronting addiction.

NA members speak of the often tragic circumstances that mark their lives prior to getting clean, and the interpersonal struggles they link to these memories of poverty, despair, and suffering. While Peter spoke of NA’s diverse membership (‘you have everyone [from] construction workers to bankers’ at meetings), all the members I encountered could point to moments of poverty and struggle, both before they began using drugs and after they got clean. Jeff, a black male in his early forties who recently finished a term as the local NA area chairperson, still struggles with basic literacy after leaving school around the eighth or ninth grade when his drug use intensified. For many years after this he was in and out of prison while using all manner of drugs. He eventually ‘got clean’ in prison where he also took a General Educational Development (high-school equivalency) course, but was, in his words, ‘passed along’ without anyone addressing his struggles to read and write beyond a remedial level. Thus, even when a clear structural impediment to economic self-sufficiency was obvious, in this case Jeff’s illiteracy, the importance of such a barrier as a determinant of life chances or the larger contextual aspects potentially contributing to addiction are ignored. Instead, Peter, Jeff, and other members understand the source of their struggles with narcotics and addiction as theirs alone.

Conclusion

NA, a free program built on embedding addicts in an extensive support system larger than themselves and not of their own making, helps many addicts restore stability to their lives. [note 9] It is, in countless ways, an admirable organization and recovery program that has done immeasurable good for people who are often neglected and ignored. Additionally, NA is of particular social value and necessity within the context of America’s long-running and destructively punitive ‘War on Drugs’, a failed campaign that has exacerbated suffering while having little to no impact on the availability, purity, and consumption of narcotics (Bourgois 2008; Lynch 2012). Within this aggressively consequential environment, NA offers haven to many as a space free from judgment, where the only criteria for participation is a desire to stop using (NAWS 1997).

The pervasiveness of NA’s ideological apparatus, particularly when the similarities to AA’s Twelve Step program are considered, is consequential, as it structures how addiction and recovery are understood in specific ways that are reflective of larger political-economic notions of worth and value that leave little room for alternative means of treatment. [note 10] As Schur (1976, 172) noted almost forty years ago, ‘individualized “tension-release” methods may help some people who already suffer from a drug habit. But they should not deflect attention from the broad socioeconomic dimensions of the problem’. NA’s approach casts addiction as an inherently individual abnormality, for which success in recovery is measured as a return to, or at least an acceptance of, individual self-reliance and economic productivity. As an approach to recovery then, it is largely dismissive of circumstance, inequality, and other structural impediments that contribute to drug use, addiction, and related practices. Members internalize a neoliberal-influenced ideology that champions self-determination, asserting they alone are responsible for their addiction but also that they suffer from an incurable, lifelong disease against which they are powerless without NA’s ‘perfect’ recovery program.

The result is a paradoxical existence for NA members. Horrific memories are frequently invoked by group members – murder, abuse, incarceration, poverty, alcohol, drug use at a young age – as part of their narrative on how they were once addicts who found redemption in NA. But these experiences and memories thereof are not treated as contributing to their addiction. Instead, addiction is some internal and inherent ‘defect’, a disease and ‘dis-ease’, returning to William’s phrasing, that must be vigilantly fought against. Success as a group member is imagined as only possible through NA’s ‘divinely inspired’ program, making failure to get and stay clean the result of the individual not truly applying organizational messages and teachings to their life. In doing so, NA conveys neoliberal sensibilities in a way that makes questioning the program impossible; this view has become, returning to Harvey (2007, 23), the ‘commonsense way we interpret, live in, and understand the world’ of addiction and recovery. For many in NA this is a welcome bargain, as the program also restores stability, offers acceptance among the fellowship of members, and helps explain past anguish.

NA is the only recovery option available to most American addicts. Yet NA is an inherently individualistic approach that ignores increasingly dire situations of economic precarity in the United States. It is an ideological system that makes it impossible to imagine and treat addiction in a way that does not champion individual responsibility through a disease model based approach to recovery. In this article, I have shown how NA’s recovery program mirrors a neoliberal worldview that champions individual self-sufficiency and financial independence while it minimizes contextual and environmental realities confronting group members. How completely longstanding NA members internalize and advocate for this ideology speaks then to the pervasiveness of neoliberalism as a way of understanding the world. In doing so it marginalizes any focus on context and situations of inequality or poverty that might contribute to drug use and addiction. This arrangement obstructs any consideration of addiction as a response to suffering and sadness, and deflects the question if NA’s ‘perfect’ program is really the only way for addicts to pursue recovery. Such a shortsighted approach ignores the ‘extreme poverty, everyday violence and victimization, and severe social marginalization’ rife in the lives of many group members (Gowan et al. 2012, 1252). Despite its benefits, NA’s ideological approach can oversimplify the nuance and complexity of addiction, potentially turning addicts who struggle with the recovery program into failures. While it has given life to Allen, William, Peter, and many others, its dominance in shaping definitions of how treatment should be structured and understood has thwarted necessary inquiry into addiction and its ancillary elements. Put simply, NA confines addicts to a recovery ideology that makes any interpersonal and social struggles their own and fosters an environment where consideration of the societal factors that contribute to addiction is difficult if not impossible.

About the author

Paul Christensen is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana. He is a cultural anthropologist specializing in contemporary Japan. His research interests include the use of psychoactive substances and recovery from addiction. He is the author of ‘Scripting Addiction, Constraining Recovery: Alcoholism and Ideology in Japan’ in Japanese Studies (2017, vol. 37, no. 3), and ‘Real Men Don’t Hold Their Liquor: The Performance of Drunkenness and Sobriety in Japan’ in Social Science Japan Journal (2012, vol. 15, no. 2). He published the book Japan, Alcoholism, and Masculinity: Suffering Sobriety in Tokyo with Lexington Books in 2014. Email: christen@rose-hulman.edu

References

Alexander, Bruce. 2010. The Globalisation of Addiction: A Study in Poverty of the Spirit. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bourgois, Philippe. 2003. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourgois, Philippe. 2008. ‘The Mystery of Marijuana: Science and the US War on Drugs’. Substance Use & Misuse 43, no. 3-4: 581–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080701884853.

Bourgois, Philippe, and Jeffrey Schonberg. 2009. Righteous Dopefiend. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brandes, Stanley. 2002. Staying Sober in Mexico City. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Broughton, Chad. 2014. Boom, Bust, Exodus: The Rust Belt, the Maquilas, and a Tale of Two Cities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown, Wendy. 2006. ‘American Nightmare: Neoliberalism, Neoconservatism, and De-Democratization’. Political Theory 34, no. 6: 690–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591706293016.

Burns, Stacy Lee, and Mark Peyrot. 2003. ‘Tough Love: Nurturing and Coercing Responsibility and Recovery in California Drug Courts’. Social Problems 50, no. 3: 416–38. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2003.50.3.416.

Cain, Carole. 1991. ‘Personal Stories: Identity Acquisition and Self-understanding in Alcoholics Anonymous’. Ethos 19, no. 2: 210–53. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1991.19.2.02a00040.

Campbell, Elizabeth, and Luke Eric Lassiter. 2014. Doing Ethnography Today: Theories, Methods, Exercises. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Carr, E. Summerson. 2011. Scripting Addiction: The Politics of Therapeutic Talk and American Sobriety. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Carr, E. Summerson. 2013. ‘Signs of Sobriety: Rescripting American Addiction Counseling’. In Addiction Trajectories, edited by Eugene Raikhel and William Garriott, 160–87. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Garcia, Angela. 2010. The Pastoral Clinic: Addiction and Dispossession along the Rio Grande. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Garriott, William. 2011. Policing Methamphetamine: Narcopolitics in Rural America. New York: New York University Press.

Garriott, William, and Eugene Raikhel. 2015. ‘Addiction in the Making’. Annual Review of Anthropology 44: 477–91. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-014242.

Gowan, Teresa, Sarah Whetstone, and Tanja Andic. 2012. ‘Addiction, Agency, and the Politics of Self-Control: Doing Harm Reduction in a Heroin Users Group’. Social Science & Medicine 74, no. 8: 1251–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.045.

Hackett, Colleen. 2013. ‘Transformative Visions Governing through Alternative Practices and Therapeutic Interventions at a Women’s Reentry Center’. Feminist Criminology 8, no. 3: 221–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085113489844.

Han, Clara. 2012. Life in Debt: Times of Care and Violence in Neoliberal Chile. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, David. 2007. ‘Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction’. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 610, no. 1: 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206296780.

Hoffmann, Heath. 2006. ‘Criticism as Deviance and Social Control in Alcoholics Anonymous’. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35, no. 6: 669–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241606286998.

Illouz, Eva. 2008. Saving the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-help. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jensen, George. 2000. Storytelling in Alcoholics Anonymous: A Rhetorical Analysis. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Kenneally, Brenda Ann. n.d. ‘Upstate Girls: A Layered Documentary Project’. http://www.upstategirls.org/index.html.

Koob, George, and Nora Volkow. 2010. ‘Neurocircuitry of Addiction’. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, no. 1: 217–38. https://doi.org/:10.1038/npp.2009.110.

Kornfield, Rachel. 2014. ‘(Re)Working the Program: Gender and Openness in Alcoholics Anonymous’. Ethos 42, no. 4: 415–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12062.

Lynch, Mona. 2012. ‘Theorizing the Role of the War on Drugs in US Punishment’. Theoretical Criminology 16, no. 2: 175–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480612441700.

Maharidge, Dale. 2013. Someplace Like America: Tales from the New Great Depression. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Maté, Gabor. 2011. In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Moore, Dawn, and Hideyuki Hirai. 2014. ‘Outcasts, Performers and True Believers: Responsibilized Subjects of Criminal Justice’. Theoretical Criminology 18, no. 1: 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480613519287.

Narcotics Anonymous Ireland. n.d. ‘NA History’. http://www.na-ireland.org/na-history/.

NAWS (Narcotics Anonymous World Services). n.d. ‘Recovery Literature in English’. Narcotics Anonymous World Services. https://www.na.org/?ID=ips-eng-index.

NAWS. (1991) 1992. An Introductory Guide to Narcotics Anonymous, Revised. Narcotics Anonymous World Services. https://www.na.org/admin/include/spaw2/uploads/pdf/litfiles/us_english/Booklet/Intro%20Guide%20to%20NA.pdf.

NAWS. (1990) 1997. The Group Booklet, Revised. Narcotics Anonymous World Services. https://www.na.org/admin/include/spaw2/uploads/pdf/litfiles/us_english/Booklet/Group%20Booklet.pdf.

NAWS. 1998. Miracles Happen: The Birth of Narcotics Anonymous in Words and Pictures. Chatsworth, CA: Narcotics Anonymous World Services.

NAWS. 2006. Public Relations Handbook. Chatsworth, CA: Narcotics Anonymous World Services. https://www.na.org/admin/include/spaw2/uploads/pdf/PR/PR_Handbook_2016.pdf.

NAWS. 2014. ‘Information about NA’ [pamphlet]. Van Nuys, CA: Narcotics Anonymous World Services. https://www.na.org/admin/include/spaw2/uploads/pdf/PR/Information_about_NA.pdf.

Peyrot, Mark. 1985. ‘Narcotics Anonymous: Its History, Structure, and Approach’. International Journal of the Addictions 20, no. 10: 1509–22. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826088509047242.

Pine, Adrienne. 2008. Working Hard, Drinking Hard: On Violence and Survival in Honduras. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pine, Jason. 2007. ‘Economy of Speed: The New Narco-capitalism’. Public Culture 19, no. 2: 357–66. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2006-041.

Prussing, Erica. 2008. ‘Sobriety and Its Cultural Politics: An Ethnographer's Perspective on Culturally Appropriate Addiction Services in Native North America’. Ethos 36, no. 3: 354–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1352.2008.00019.x.

Rafalovich, Adam. 1999. ‘Keep Coming Back! Narcotics Anonymous Narrative and Recovering-Addict Identity’. Contemporary Drug Problems 26, no. 1: 131–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145099902600106.

Reith, Gerda. 2004. ‘Consumption and Its Discontents: Addiction, Identity and the Problems of Freedom’. British Journal of Sociology 55, no. 2: 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2004.00019.x.

Roberts, Elizabeth F. S. 2014. ‘Petri Dish’. Somatosphere, 31 March. http://somatosphere.net/2014/03/petri-dish.html.

Rose, Nikolas. 2000. ‘Government and Control’. British Journal of Criminology 40, no. 2: 321–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/40.2.321.

Schüll, Natasha Dow. 2012. Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schur, Edwin. 1976. The Awareness Trap: Self-Absorption instead of Social Change. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Seddon, Toby. 2007. ‘Drugs and Freedom’. Addiction Research & Theory 15, no. 4: 333–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350701350262.

Snyder, Jeffrey, and Daniel Fessler. 2014. ‘Narcotics Anonymous: Anonymity, Admiration, and Prestige in An Egalitarian Community’. Ethos 44, no. 4: 440–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12063.

Stewart, Kathleen. 1996. A Space on the Side of the Road: Cultural Poetics in an ‘Other’ America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tiger, Rebecca. 2013. Judging Addicts: Drug Courts and Coercion in the Justice System. New York: New York University Press.

Wacquant, Loïc. 2009. Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Wacquant, Loïc. 2015. ‘Afterward: Plumbing the Social Underbelly of the Dual City’. In Invisible in Austin: Life and Labor in an American City, edited by Javier Auyero and Loïc Wacquant, 264–72. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Wilcox, Danny M. 1998. Alcoholic Thinking: Language, Culture, and Belief in Alcoholics Anonymous. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Endnotes

1 Back

‘The program’ refers to NA’s recovery program that combines working the Twelve Steps, reading and reflecting upon organizational literature, and regular meeting attendance. Working the program can also include getting and collaborating with a sponsor. More information can be found on NA’s website at http://www.na.org.

2 Back

‘Clean’ is NA parlance for not having any addicting substances in one’s body. It is discussed in detail later as it pertains to how members speak of themselves in terms of how long they have been clean.

3 Back

I use ‘meaningful work’ to refer to stable, long-term employment that affords an employee economic stability and optimism for a better future. More specifically, I use the decline of meaningful work as shorthand to reference the rapid replacement of blue-collar industrial work with service-sector employment across the United States as a hallmark of neoliberalism’s growing ideological influence and impact (Bourgois 2003, 114; Bourgois and Schoenberg 2009, 148; Broughton 2014, 256; Maharidge 2013, 101).

4 Back

All names are pseudonyms to protect the identity and anonymity of interviewees.

5 Back

Rafalovich (1999, 149) discusses similar practices wherein addicts describe how their addiction ‘is believed to talk its victims into using drugs through a variety of self-rationalizations’.

6 Back

Crack is powder cocaine mixed with baking soda and water and then heated to form a crystalline ‘crack rock’ that is smoked by the user. It gives a short, intense high many former users describe as powerfully addicting.

7 Back

See both the NAWS (n.d.) ‘Recovery Literature in English’ webpage and the NAWS ([1991] 1992) Introductory Guide for more information.

8 Back

See also Koob and Volkow 2010, 217 and Maté 2011, 155 for more on this.

9 Back

Thank you to Elizabeth F. S. Roberts for her insightful comments on this section of the article.

10 Back

AA and NA are not absolutely inflexible, but digression from the established program is rare (Kornfield 2014; Prussing 2008).