Introduction

Critical perspectives on US global health partnerships in Africa and beyond

—

Partnership is a central ideal in US interventions into global health. From major funding efforts such as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) New Partners Initiative to university research and teaching programs, the promotion of partnership with lower income countries – particularly in Africa – has become a defining feature of American global health endeavors. Such promotion is part of the institutionalization of cooperative arrangements between United States and African organizations (for example, legal partnership agreements, shared grants, and memoranda of understanding), and the small-scale day-to-day practices and interactions of multinational staff who negotiate partnerships at interpersonal and administrative levels. Although the use of the term ‘partnership’ in development circles dates back to the late 1960s (Mercer 2003; Jensen and Winthereik 2012), the term rose to prominence amid the unfolding of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the subsequent emergence of global health as a new field of practice. Paul Farmer and colleagues in Haiti gave it pride of place in 1987 by naming their organization Partners in Health. Through partnership, progressive medical clinicians and researchers sought to signal a deep, shared, and ongoing commitment to improving health and a rejection of top-down, neocolonial approaches.

Over the past thirty years, partnership has become a programmatic priority and affective ideal that practitioners struggle to make a political reality. Writing in the Lancet in 2009, a team of prominent scholars sought to define global health and differentiate their work from earlier endeavors by pointing to the central importance of partnership: ‘The preference for the use of the term global health where international health might have been previously used runs parallel to a shift in philosophy and attitude that emphasizes the mutuality of real partnership, a pooling of experience and knowledge, and a two-way flow between developed and developing countries’ (Koplan et al. 2009, 1994–95). As calls for partnership have grown (Academy of Medical Sciences 2012; Jones 2016; Muir et al. 2016), social scientists have begun to interrogate what ‘real partnership’ looks like, means, and does in practice (Citrin et al. 2017; Crane 2010, 2013; Crane et al. 2017; Geissler and Tousingant 2017; Moyer and Nguyen 2017; Okwaro and Geissler 2015; Wendland 2017). However, more ethnographically and historically informed interdisciplinary research is needed to better understand how partnerships have become a core element of global health work and how the future(s) of such partnerships may yet unfold.

In this spirit, this issue examines the longue durée of partnerships in global health, exploring how and why they are formed, persist, change, and/or dissolve over time, and how differently situated actors have understood and constructed partnerships in and across various locales. The authors also attend to the ways that broader political, economic, cultural, and academic settings give rise to, and reinforce, partnership as a mode of process and an ongoing aspirational ideal.

This project began in 2015 at the University of Washington with the aim of drawing together scholars from a range of disciplines – stretching from medicine and history to anthropology and philosophy – to examine global health partnerships from critical and humanistic perspectives.[note 1] Since then, political and funding terrains have shifted in dramatic and as yet unresolved ways – most notably with the election of President Trump in the United States and nationalist movements gaining speed across Europe. The uncertainty of global health as a US political, humanitarian, and funding priority in this new era only underscores for us the importance of working towards a more just and equitable ethic of global partnership and collaboration, both within and across borders and disciplines.

Inequities and obfuscations

One of the central concerns animating the essays included here is whether the ‘two-way flow’ imagined by Koplan and colleagues (2009) is not only bidirectional but fair. While global health partnerships often invoke ideas of equality, equity, and mutual benefit, many authors in this issue voice the suspicion that appeals to equal partnership in fact work to mask deeply unfair institutional arrangements. Yap Boum observes that while Western institutional partners tend to provide ‘funds and technical expertise’ in research partnerships, African partners are most often called upon to provide ‘sites, patients, samples, and data’. Iruka Okeke notes in this issue that a hallmark of many partnerships is, in fact, their temporal fragility: ‘enough post-partnership debris litters many an African hospital, university, or even curriculum vitae for us to be sure that many are not sustained’.

These material flows echo and reinforce, even if unintentionally, neocolonial economies of extraction, whereby the raw material of global health work is extracted from Africa; transformed by Western scientists, experts, and institutions into more valuable products; and then returned and marketed to African states as essential health interventions or products. This dynamic is particularly notable in the practice of what Sarah Gimbel and colleagues call ‘data vacuuming’, whereby global health donors and their international nongovernmental partners engage in extensive data extraction from health systems as part of an expanding audit culture in global health and a broader knowledge economy in which data is the ‘new oil’.

Several essays connect these global geopolitical trends to specific domains and types of partnership. Adam Warren’s analysis of conflicts between Peruvian scientists and a 1949 United Nations’ commission on coca consumption highlights the complexity of international research collaborations prior to the contemporary era of global health. Warren’s essay and Rossio Motta’s response consider how inequalities and misunderstandings can pervade research relations in global South countries – through forms of ‘internal colonialism’ – as well as between North and South collaborators. Tamer Fouad offers a postcolonial critique of global oncology research collaborations that create forms of ‘academic dependency’ that severely limit the ways that non-Western collaborators can contribute to knowledge production. And David Citrin and colleagues explore the opportunities, anxieties, and tensions of a novel public-private partnership in Nepal, where efforts to deliver high-quality, free-to-access care through this partnership are set against the backdrop of Nepal’s increasingly privatized and fragmented health system.

Many of these essays underscore the importance of attending to broader political and economic contexts that provide the sculpting conditions under which partnerships are formed and sustained. One of the central, and under-recognized, forces fueling global health partnerships is the extensive dismantling of health systems, especially in many African countries: it is only in the absence of adequate health system capacities that modalities of partnership become necessary.

A multiplicity of meanings

Interrogating the politics of partnership, these essays also document the extensive vocabulary used to define and qualify such joint endeavors. Okeke’s essay insightfully traces the differences between ‘collaborations’ and ‘partnerships’, noting that the latter implies a more limited temporality: ‘for now’, but not forever, or for good. Indeed, ‘many a project carried out by reflective partners ends with a worried discourse about the long-term prospects’, Okeke writes; and because partnership lacks the sense of mutual accountability that long-term research collaborations hold, the likelihood of disappointment, misunderstanding, or mistreatment grows.

Several authors discuss the affective associations that partnerships often evoke, including those of prenuptial contracts, marriage, and divorce (Okeke; Boum), and friendship (Grant; Chhem). Yet as Jenna Grant notes in her account of Russian government and US corporate medical aid to a government hospital in Cambodia, the obligations of ‘friendships’ are rarely clear and are frequently imbued with complex histories and geopolitics. Rethy Chhem’s response to Grant reminds us that we must attend not only to the affective terms of such friendships, but to their material – and even atomic – residues. Attending to such complexity, Janelle Taylor aptly identifies partnership as a ‘boundary object’ whose multiple meanings ‘facilitate mutual misunderstandings’. Such misunderstandings can be remarkably productive for various global health practitioners while operating across ‘steep gradients of inequality’.

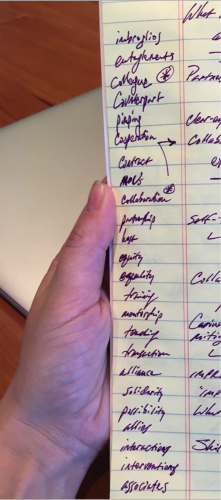

Figure 1. A partial list of terms used to describe partnerships and partners, collected by our colleague Ron Krabill at a workshop on this topic in February 2017.

Figure 1. A partial list of terms used to describe partnerships and partners, collected by our colleague Ron Krabill at a workshop on this topic in February 2017.Other essay writers probe that inequality, delineating its various dimensions and documenting how some contemporary global health practitioners seek to rework and reimagine their endeavors. Carina Fourie uses the tools of philosophical and ethical analysis to parse the various forms of inequality at play in global health partnerships. Inequality, she argues, relates to material resources and programmatic decision making but also, importantly, encompasses the refusal by Northern partners to acknowledge the extent and diversity of their disproportionate power. Possibilities for improving partnerships also exist at more incremental, practical levels. Rather than emphasizing an ethic of parity, Boum writes that ‘a “true” partnership should be mutually beneficial’. What seems to matter most to Boum and several other contributors is that all parties in a partnership feel that they gain something substantial and clearly understand what each party will gain, even if the benefits are not the same for all.

Johanna Crane points to a specific site for reducing disparities in academic global health partnerships: the ‘mundane’ work of accounting, compliance, and risk management. Although such systems overwhelmingly operate to shore up US institutions’ fiscal and administrative control of partnerships, Crane contends that ‘workarounds’ and creative compliance can offer microlevel opportunities for confronting and mitigating the inequalities between American and African staff. Finally, Nora Kenworthy directs our attention to the future of partnerships by considering the phenomena of global health crowdfunding and the Silicon Valley ethos that undergirds it. Examining the origins and operations of Watsi, a highly successful platform that fundraises to cover the expenses of medical patients in the global South, Kenworthy points to new and uneasy pairings of proximity and distance, suspicion and transparency, and urges anthropologists to investigate the ethical and political issues that such partnerships occlude.

Universities and global health

Two abiding themes run through all of these essays: first, the vexed relationship between global health partnerships and national health care systems; and, second, the necessary role of universities in helping to rethink that relationship. These essays recognize that partnerships involving university actors have often worked to undermine or subvert health care systems; yet they insist that researchers, students, and administrators at universities in the global North and the South are key to reimagining and reconfiguring partnerships in ways that will support and strengthen those systems. A public discussion between Paul Farmer and Iruka Okeke at the University of Washington in February 2018, reported on here by Celso Inguane, underscored this point. As both discussants agreed, through teaching, mentoring, and caring – as well as conducting research – universities have a mission to serve the broader publics that support them. Farmer and Okeke drew lessons from their experiences working at institutions of higher learning in Haiti, Nigeria, Rwanda, and the United States.

At a time when global partnerships have become a routine element of university vision statements, we must consider more carefully what work is being undertaken and which publics are being served as visions become reality. Much as universities played an important role in generating the field of global health, they continue to play an important role in elaborating and institutionalizing global health partnerships. Scholars, students, and administrators from universities in the global North and South are uniquely positioned to shed light on the realities of global health partnerships and to work to make them more mutually beneficial and equitable for all of those involved.

Table of contents: Interventions

What the word ‘partnership’ conjoins, and what it does

– Janelle S. Taylor

Partnerships for now?

– Iruka N. Okeke

Is Africa part of the partnership?

– Yap Boum II

Collaboration and discord in international debates about coca chewing, 1949–1952

– Adam Warren

Commentary – Habit or addiction? Collaboration and misunderstandings in international debates about coca-leaf chewing

– Rossio Motta-Ochoa

Friends, partners, and orphans: Relations that make and unmake a hospital

– Jenna Grant

Commentary – Cobalt diplomacy in Cambodia

– Rethy Chhem

Donor data vacuuming: Audit culture and the use of data in global heath partnerships

– Sarah Gimbel, Baltazar Chilundo, Nora Kenworthy, Celso Inguane, David Citrin, Rachel Chapman, Kenneth Sherr, James Pfeiffer

NGOs, partnerships, and the public-private discontent in Nepal’s health care sector

– David Citrin, Hima Bista, Agya Mahat

Academic dependency: A postcolonial critique of global health collaborations in oncology

– Tamer M. Fouad

The trouble with inequalities in global health partnerships: An ethical assessment

– Carina Fourie

Global health enabling systems: Accounting and critique in the era of ‘America First’

– Johanna T. Crane

Drone philanthropy? Global health crowdfunding and the anxious futures of partnership

– Nora Kenworthy

Critical perspectives on global health partnerships in Africa

– Celso Azarias Inguane

About the authors

Nora Kenworthy is Assistant Professor in the School of Nursing and Health Studies at the University of Washington, Bothell. Her recent book, Mistreated: The Political Consequences of the Fight Against AIDS in Lesotho (Vanderbilt University Press, 2017) examines the unexpected political costs and missed opportunities for deepening democracy during the global HIV epidemic. Her more recent research examines the industry and emerging cultures of crowdfunding for health care in the United States and abroad.

Lynn M. Thomas is Professor of History and Adjunct Professor in Anthropology and in Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies at the University of Washington, Seattle. Her research has examined the history of reproductive and gender politics in Kenya and South Africa, including through her book, Politics of the Womb: Women, Reproduction, and the State in Kenya (University of California Press, 2003).

Johanna Crane is the author of Scrambling for Africa: AIDS, Expertise, and the Rise of American Global Health Science (Cornell University Press, 2013) and holds a PhD from the UCSF/UC Berkeley Joint Program in Medical Anthropology. She is Associate Professor of Science, Technology, and Society at the University of Washington, Bothell and Adjunct Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Washington, Seattle.

References

Academy of Medical Sciences. 2012. Building Institutions through Equitable Partnerships in Global Health: Conference Report. London: Academy of Medical Sciences, the Royal College of Physicians, the Wellcome Trust, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Universities UK. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/35256-134337813321.pdf.

Citrin, David, Stephen Mehanni, Bibhav Acharya, Lena Wong, Isha Nirola, Rebkha Sherchan, et al. 2017. ‘Power, Potential, and Pitfalls in Global Health Academic Partnerships: Review and Reflections on an Approach in Nepal’. Global Health Action 10 (1): 1367161. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1367161.

Crane, Johanna. 2010. ‘Unequal “Partners”: AIDS, Academia, and the Rise of Global Health’. Behemoth 3 (3): 78–97. https://doi.org/10.6094/behemoth.2010.3.3.685.

Crane, Johanna. 2013. Scrambling for Africa: AIDS, Expertise, and the Rise of American Global Health Science. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Crane, Johanna, Irene Andia Biraro, Tamer M. Fouad, Yap Boum II, and David R. Bangsberg. 2017. ‘The “Indirect Costs” of Underfunding Foreign Partners in Global Health Research: A Case Study’. Global Public Health. Published online September 16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1372504.

Geissler, Paul Wenzel, and Noémi Tousignant. 2017. ‘Capacity as History and Horizon: Infrastructure, Autonomy and Future in African Health Science and Care’. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue canadienne des études africaines 50 (3): 349–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2016.1267653.

Jensen, Casper Bruun, and Brit Ross Winthereik. 2012. ‘Recursive Partnerships in Global Development Aid’. In Differentiating Development: Beyond an Anthropology of Critique, edited by Soumhya Venkatesan and Thomas Yarrow, 84–101. New York: Berghahn Books.

Jones, Andrew. 2016. ‘Envisioning a Global Health Partnership Movement’. Globalization and Health 12 (1): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-015-0138-4

Koplan, Jeffrey P., T. Christopher Bond, Michael H. Merson, K. Srinath Reddy, Mario Henry Rodriguez, Nelson K. Sewankambo, and Judith N. Wasserheit. 2009. ‘Towards a Common Definition of Global Health’. Lancet 373 (9679): 1993–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9.

Mercer, Claire. 2003. ‘Performing Partnership: Civil Society and the Illusions of Good Governance in Tanzania’. Political Geography 22 (7): 741–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(03)00103-3.

Moyer, Eileen, and Vinh-Kim Nguyen. 2017. ‘Collaborative Conundrums and Respectful Partnerships: Medical Anthropology and Disciplinary Others’. Medicine Anthropology Theory 4 (2): i–iii. https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.4.2.520.

Muir, Jonathan A., Jessica Farley, Allison Osterman, Stephen Hawes, Keith Martin, J. Stephen Morrison, and King K. Holmes. 2016. Global Health Programs and Partnerships: Evidence of Mutual Benefit and Equity. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Okwaro, Ferdinand Moyi, and Paul Wenzel Geissler. 2015. ‘In/dependent Collaborations: Perceptions and Experiences of African Scientists in Transnational HIV Research’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 29 (4): 492–511. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/maq.12206.

Wendland, Claire. L. 2017. ‘Opening up the Black Box: Looking for a More Capacious Version of Capacity in Global Health Partnerships’. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue canadienne des études africaines 50 (3): 415–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2016.1266675.

Endnotes

1 Back

For their support of this project, we thank the Walter C. Simpson Center for the Humanities and the Population Health Initiative at the University of Washington. We are also grateful to Taylor Soja for helping to organize the workshops, materials, and events related to the project.