But are they actually healthier?

Challenging the health/wellness divide through the ethnography of embodied ecological heritage

—

Abstract

Introduction

What it means to be or become healthy is the subject of seemingly never-ending scholarly and popular inquiry. Though at first glance oxymoronic, the broad definition ratified by the World Health Organization in 1946 – ‘health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ – lends itself well to the local focus of most ethnographic research (WHO 1946, 1). This definition accords with the holistic focus of ethnography and allows for the consideration of social practice in the definition and measurement of the health of communities and individuals. The definition also moves away from dichotomous divisions, problematized by medical anthropologists (Kleinman 1989; Good 1993; Reeve 2000), between mind/body, belief/knowledge, and wellness/health. I have myself sought to define health in my research both broadly and locally, looking beyond physical measurements, which has allowed for a deepening of my understanding of how health is defined in the communities with whom I have studied.

The WHO’s early definition sounds exactly like what an anthropological researcher would desire, but there persists a call for more concrete, physiological health indicators and metrics from public health organizations and biomedical practitioners. Whenever I discuss the research I have conducted among Caribbean and Latin American communities, I am still asked the question about whether the individuals and communities in my studies are ‘actually healthier’. This isolation and privileging of what is understood as physical health is not limited to people working in biomedicine, as anthropologists and laypeople alike have also posed the question. Slightly bewildered but not wholly surprised, I have responded by incorporating anthropometric measurements in some studies, cataloguing blood pressure and BMI, and attempting to provide the evidence that seems to be desired. But while my research participants certainly talk about physical health, they rarely separate it from the social or mental aspects of health. In response to this, I have turned my attention to developing a framework that foregrounds the intersection of social practice and the physical body. Demonstrated here with brief ethnographic examples, I hope that this framework can help theorize how health is connected to practice through the body and the role that social and mental well-being play in this process.[note 1]

This framework for understanding health, which I call ‘embodied ecological heritage’ (EEH), takes into account how the body changes through engaging in specific everyday practices, in which it interacts with its surrounding environment, broadly defined, in ways that are considered ‘traditional’ by the practitioners. Criteria for what is ‘traditional’ or what forms part of ‘heritage identity’ are defined by community members. For example, community members might conceive of growing and eating corn as traditional practices that are both part of who they are and what makes them healthy community members, and how engaging in these practices affects their bodies would therefore be part of their embodied ecological heritage.

EEH was originally theorized in response to the lack of adequate conceptualization of the links between a healthy body (and mind) and traditional ecological knowledge and practice, both in scholarly examinations and popular discourse. It takes into account gaps in existing discussions of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and its link to health, which, in many cases, have focused on the use of traditional medicinal plant knowledge to promote wellness (Reyes-García et al. 2006; Baumflek, DeGloria, and Kassam 2015) and on the use of ‘folk’ remedies in the provision of healthcare (Murquia, Peterson, and Zea 2003). With the EEH framework, I aim to go beyond the intersections of ethnobotanical and ‘alternative health practices’ toward a richer understanding of how bodies change through ecological interactions. These broader links are just beginning to be explored through ethnographic research (Baines 2016a). Rather than simply assert that measures of health that emphasize social dimensions or local definitions should be considered (and they should), the EEH framework brings the physical body into the discussion with a focus on how bodily health is linked to embodied practices. Sensory experiences provoke real changes in the body, and these can be measured and discussed just as health practitioners might measure and discuss nutrition or exercise.

Scholars have long recognized the tension between biomedical models of health and more holistic conceptualizations that are used in their communities of study (Arquette et al. 2002; Donatuto, Campbell, and Gregory 2016). While this recognition is critical to enhancing the provision of health care in historically marginalized communities, it often serves to reify a dichotomy between ‘actual’/physical health and social/mental health. There are limitations to medical pluralistic approaches that focus on understanding folk knowledge or indigenous knowledge but still within the context of providing biomedical care. In health discussions involving indigenous, immigrant, or other marginalized groups, ‘bodily knowledge often has been trivialized in favor of more scientific, objective ways of knowing’ (Tangenberg and Kemp 2002, 9). The subjugation of bodies and knowledges, theorized perhaps most prominently by Foucault (1973, 1977) and also studied by critical medical anthropologists (see for example Baer, Singer, and Susser 2003), is premised upon the idea that there is a divide between ‘actual’ health and other ways of understanding wellness and the body. The EEH framework aims to challenge the implicit passivity in these discussions, focusing on bodily practice. However, I wish to emphasize that there need not be a strong boundary between these practices and the knowledge that is necessary for their deployment. I recognize that some working in health initiatives argue that having knowledge does not necessarily lead to behavior based on that knowledge (see for example Ito 1999). Having ‘traditional’ or heritage knowledge or, indeed, knowing anything at all does not necessitate action. However, considering the lived experience of the body in practice alongside what is more commonly defined as ‘knowledge’, which is further unpacked in the discussion that follows, allows for a consideration of a kind of ‘cognitive phenomenology’ or a fusing of theoretical perspectives often considered at odds with each other.

In his discussion of the development of skills in relation to living in, modifying, and learning from the natural environment, Ingold (2000) explores these connections. In his ‘processing loop’ model, experiences of sensation, touch, and taste, for example, are indicators provided by the natural environment regarding the properties and effectiveness of a food, herb, or medicine. He writes that processing loops ‘yield intelligent action’ and ‘are not confined to some interior space of the mind but are free to penetrate between body and environment’ (Ingold 2000, 165). Taking the generation of knowledge as an ongoing process in which individuals learn about their bodies (and, consequently, I would add, bodily health) in a ‘give and take’ interaction with their natural environment, Ingold incorporates ideas of sensory experience and cognitive patterning in his understanding of how individuals operate in the world. I have taken inspiration from this model to help explain the phenomenological connections between health and environmental heritage.

‘Embodied ecological heritage’

Each of the constituent terms of ‘embodied ecological heritage’ (EEH) requires definition and clarification. Each term was chosen carefully, given its utility over other perspectives and approaches. Below, each of the terms is unpacked and set alongside alternate perspectives to illustrate this utility.

‘Embodied’

Health and wellness are theorized, observed, and measured using a wide-range of perspectives and instruments. A focus on the individual body, including the effects of daily sensory experiences and practices on the body, lends itself to a phenomenological perspective. The term ‘embodied’ and the related ‘embodiment’ reflect this phenomenological root.

A phenomenological consideration begins with the individual body, and Heideggerian phenomenology considers all human experience to be grounded in time and situated in space.[note 2] Understanding space in terms of the landscape or the changing environment is fundamental, I argue, to understanding ‘being well’. Time, more specifically the continuity of time that Heidegger conceptualizes, is also relevant to thinking about heritage (considered in greater detail below) as both the continuity of work, skill, or practice, in the Bourdieuian sense, and its resultant embodiment. In recent decades, anthropological engagements with this philosophy make the embodied nature of the practice of wellness more explicit (see for example Csordas 1994; Holmes 2013). Time and space in which practice occurs are critical to the experience of the embodiment of wellness. These temporal and spatial dimensions are reflected in many communities’ understanding of wellness. Buddhist conceptions of becoming well, for example, combine a processual focus (a ‘becoming’ well, rather than simply ‘being’) with an attention to the importance of a particular place or space to achieve health and well-being (Walsh 2007). Among Maya people, the relationship of process to wellness is also expressed in concerns about the ability to work and thereby to make socially prescribed contributions to the community (Baines 2016). When illness does not interrupt this ability, the individual is well in his or her world.

Of course, as Bruhn and colleagues (1977, 210) write, ‘individuals do not work toward, or experience, wellness in the same way’, even if they are subject to the same environmental or socio-cultural pressures. In this sense, wellness is an appropriate topic for phenomenological research because wellness is ‘rooted in autobiographical meanings and values, as well as involving social meanings and significance’ (Moustakas 1994, 103). Wellness is often taken to mean the subjective experience of health (Mackey 2009), and phenomenology seeks to reveal the individual’s own understanding of being and living in their own body: the subjectivities of experience.

The anthropological deployment of phenomenology in relation to health owes a debt to Kleinman’s (1989) problematizing and defining of the categories of ‘disease’, ‘sickness’, and ‘illness’, through which the term ‘illness’ came ‘to specify an individual’s personal experience with affliction(s)’ (Harvey 2008, 580). In more recent clinical settings, nurses have noted that in considering the experience of caring, healing, and wholeness, they cannot disregard people’s lives beyond being ill or well (Wojnar and Swanson 2007). This holistic focus is decidedly anthropological. In anthropology, phenomenological theory has been used ‘as a starting point to counter what [anthropologists] see as the mistaken enterprise of interpreting embodied experience in terms of cognitive and linguistic models of interpretation’ (Lock 1993, 143). Indeed, both Kleinman (1989) and Lock (1993) value a focus on individual embodied knowledge as critical to understanding what makes a person well. To this end, narrative collection and in-depth, open-ended interviews with theme extraction and analysis have become standard ways ‘to identify themes that are essential, not incidental, to this lived experience’ (Healey-Ogden and Austin 2011, 86).

In his discussion of Maya ‘wellness-seekers’, Harvey (2008) describes how his research participants consider their bodily experience to be sharable, a perspective that troubles any focus on the individual, physical body as the site of illness and wellness. The discussions of the tension between the treatment of the individual body and the incorporation of natural processes, the family, and the community that is highlighted in discussions of ethnomedical approaches to health care (Murquia, Peterson, and Zea 2003; Reeve 2000) are helpful in pushing forward a phenomenological perspective, but they focus on illness treatment rather than health maintenance. While the individualized focus of phenomenology might, at first, seem at odds with this perspective, the reverse could be argued; an interpretive approach to understanding Maya lived experience, in this case, has great potential to reveal the reality of shared bodies to the researcher in a way that thinking about the body as an objective, physical reality could not. That said, phenomenology’s origin in Western philosophy, and its resultant assumptions of individuality, should not be overlooked.

Attempts have been made to take phenomenological theory generally, and the concept of embodiment specifically, beyond the notion of the singular body. Australian Aboriginal conceptions of well-being reflect a greater emphasis on the ‘demands and obligations that constitute and reconstitute self-other relationships’ (Heil 2009, 88), and less emphasis on the individualized embodiment of wellness. Mark and Lyons (2010), in their study of Māori well-being, note the significance of family relationships (whānau/whakapapa) and land (whenau) as fundamental to a person’s health. They propose a model of well-being called Te Whetu (The Star), with five interconnected aspects: mind, body, spirit, family, and land (Mark and Lyons 2010). Adelson (2009) argues that among the Canadian Cree, well-being is also connected to land in three ways: literally, symbolically, and strategically. These connections, which parallel my research in important ways, represent a kind of ‘phenomenological orienteering’ (Atleo 2008) or a defining of being (well) in the world by navigating through it. Although individuals embody their own wellness experience, many social and environmental forces shape the nature of this embodiment. In many cultures and communities, including in the Maya community of Santa Cruz, Belize, personal autonomy is valued, though it is ‘not independence but an autonomy that is continuously constituted within the social’ (Heil 2009, 109). The social, then, along with the environmental, must be considered in this discussion.

A focus on embodied experience helps collapse mind/body dualisms by shifting from the distinction between what is thought and practiced to what is considered a whole experience. I argue that this focus on the ‘whole experience’ goes far to facilitate a collapse of the health/wellness/happiness distinctions. My choice of the term ‘embodied’ reflects an effort to break down these divisions, as it carries a critique of the assumption that ‘health’ is an objective, physical measure while ‘wellness’ is a subjective one, an assumption that is associated with biomedical models of health (Good 1993). ‘Embodiment’ is more holistic, while public health-oriented approaches often focus on behavioral interventions and objective measures of health status (Levin and Browner 2005; Donovan 1995) and are incomplete at best. While this perspective may be less overtly politicized than is common in critical medical anthropology (Baer, Singer, and Susser 2003), a focus on embodiment does leave room for considering multiple inputs, including external sociopolitical factors, such as health care access or structural racism. This makes it an ideal perspective for considering the multiple ways that wellness is constituted.

I argue that a consideration of the embodied lived-experience need not exclusively focus on the individual body, but should incorporate social, political, and ecological aspects of being well in the world. This incorporation has been theorized (Scheper-Hughes and Lock 1987; Hsu 2007) but not fully operationalized. Recent research at the intersection of indigenous health and ecological well-being has made inroads into defining and using social, political, and ecological health indicators that are generated through the lived experience of individuals in the communities where they are deployed (Parlee et al. 2005; King and Furgal 2014; Donatuto, Campbell, and Gregory 2016). While these studies can be seen as blueprints for strengthening community health and environmental policy, they still maintain divisions between physical and social variables. By linking embodiment to ecological heritage practices, as described below, I hope to address this shortcoming and demonstrate that specific, measurable practices are linked to wellness in holistic ways.[note 3]

‘Ecological’

I use ‘ecological’ in this discussion in two primary ways. First, it is used to refer to direct relationships with aspects of the natural environment, such as land, plants, animals, and seasonal weather cycles. In this usage, ‘ecological’ is considered an alternative to more explicitly social, political, or cognitive ways of describing and understanding human behavior. Second, the term is used to refer, more specifically, to the body of literature on ‘traditional ecological knowledge’ or TEK. In this usage, ‘ecological’ is meant to both reflect a critique of the terms ‘traditional’ and ‘knowledge’ while also acknowledging that TEK scholarship has informed the theoretical framework of EEH and the ethnographic work presented below.

Ethnobiological and ethnoscientific scholars interested in the classification, documentation, and preservation of what has been referred to as ‘indigenous knowledge’ have used the term ‘TEK’, in sometimes simplistic ways, in their work since the 1980s. As Dove (2007) rightly notes, indigenous knowledge is heterogeneous and the distinction between what is and is not ‘indigenous’ is ‘complicated’ and nuanced and often heavily politicized. (This observation is also true of generalized conceptualizations and definitions of heritage discussed in the following section.) Growing out of ethnobiological pursuits is ethnoecology, defined as the study of ‘indigenous perceptions of “natural” divisions in the biological world and plant-animal-human relationships within each division’ (Posey et al. 1984, 95). Ethnobiologists and ethnoecologists today typically emphasize fluidity and change, having argued against the ‘paradigmatic monocultures’ that have characterized ethnoscientific treatment of TEK and in ‘response [to the assumptions of the] immutability of traditional knowledge that leads to caricature and parody’ (Nazarea 1999, ii). A 2002 collaborative report on TEK exemplifies this, asserting the importance of ‘appreciating traditional knowledge not as sets of information but as integral components of other living and dynamic societies and cultures’ (International Council for Science 2002, 17), in essence, as a process, not a product. Addressing the temporal and linguistic setbacks that continue to plague the concept of TEK, Pierotti and Wildcat (2000, 1334) note, ‘although views covered by TEK are described as “traditional”, this should not be taken to mean that they cannot change’. Noting that ‘understanding people’s ecological knowledge requires intimate conversations because human-environment relations are nuanced’ (Wolverton, Nolan, and Fry 2016, 75), scholars continue to emphasize the importance of ethnographic methods for understanding the processual significance of the generation and maintenance of traditional knowledge.

Researchers, seeking to follow a grounded approach to capture the ecological validity of TEK systems, have long sought to counter remnants of past dichotomous thinking that privilege ‘knowledge’ over ‘belief’. Early examples include the ‘knowledge gathering’ method to assert that TEK manifestations are ‘no accident’ and that local vantage points are ‘systematic’ (Posey et al. 1984). Arquette and colleagues (2002) have documented the adverse health effects communities experience when they are forced to abandon traditional environmental and cultural practices. Other studies have differentiated their methods from simple knowledge acquisition. Stephenson (1999) highlights how fluidity is captured through an ethnoecological perspective; when looking at traditional nonindustrial farming, he argues, scholars should focus not on the biological components of crops but on farm ‘management strategies’. Pierotti and Wildcat (2000) find similarities in TEK and ecological knowledge, noting a major theme of TEK is that all things are connected and emphasizing that this is a ‘practical recognition’ of the literal interconnectedness of all living things. Similarly, Ingold (2007, 308) writes about ‘knowing by way of … practice’.

Process-oriented studies would seem, then, to be of benefit to understanding TEK and its ongoing use in anthropological discussions. While scholars have called for the investigation of processes rather than the cataloging of knowledge, Ross (2002, 126) argues that ‘basic processes of knowledge formation and transmission in changing contexts … receive little attention in ethnoecology’. A more recent push for process-oriented studies asks scholars to move beyond describing TEK in terms of what people know and how they talk about it, to understanding how such knowledge changes as part of an ongoing interconnected and interactive process. This emphasis on interconnection informs the EEH framework, particularly as it impacts the construction of ecological heritage. Without recognizing the dynamic nature of ecological knowledge and practice, this heritage is difficult to understand or measure.

‘Heritage’

The term ‘heritage’ carries with it the dangers of a theoretical rabbit hole. However, it is precisely the potentially problematic nature of the term that makes it attractive to me for my discussion of the health/wellness dichotomy. Given the malleable and politicized nature of the definition of ‘heritage’, there is great need for analysis and clarification, which can be done, I argue, through considering the bodily experience of ecological practice.

‘Traditions’ and ‘histories’ begin to evoke what is meant by ‘heritage’, yet they fail to capture the dynamic nature of the construction of the past in the present. Chan (2005, 66) clarifies that ‘heritage is an interpretation, adaptation, exploitation, or a creation in the present rather than a preservation of what actually exists’; traditional knowledge and practices therefore play a role in its construction. ‘Heritage’ evokes the interaction of the past in the present. This creation process has a direct effect on a person’s lived experience. For example, Maya heritage and identity are created, most notably, through the daily preparation and consumption of corn tortillas (Baines 2016b). A Maya person’s experience of preparing and eating tortillas is part of their embodied heritage, fundamentally different from an abstracted list of traditions or collections of knowledge. People can interact with heritage in multiple ways and, because it is both fluid and embodied, multiple ‘heritages’ can exist not only in one community but also in one person. Rather than being problematic, the existence of multiple heritages necessitates a phenomenological approach in order to capture how they are experienced differently in and between individuals.

It seems clear that cultural heritage explicitly incorporates traditions and practices inherited and passed down and, therefore, cannot be seen as simply objects or monuments (Blake 2002). In this sense, it could be argued that each person holds a unique environmental heritage, beyond that which is inherited, one that is related to their own interactions with the natural world. It can be argued that the knowledge to be preserved can have been gleaned from personal experience in the natural environment. In the sense that children pick fruit from trees and men use sticks to make holes to plant corn, there is a strong tangible element to environmental heritage. This tangibility, and the direct experience of the body, supports the observation that heritage is not static but rather maintains fluidity through practice.

A discussion of environmental heritage requires a particular set of considerations, for example, the level of engagement an individual has with their natural environment or how that environment has changed over time. I argue that issues related to representation, authenticity, and significance are part of this discussion, just as they are when considering the preservation of an ancient building. McKercher and du Cros (2002) distinguish between ‘intangible’ and ‘tangible’ heritage in their discussion of the management of cultural assets. Environmental knowledge is classified as intangible heritage, which, they argue, requires cooperation from the people who hold it in order to be preserved (McKercher and du Cros 2002, 83).

It is helpful to think about environmental heritage as both a physical landscape and a ‘cultural space’ (McKercher and Cros 2002, 94). Setten (2005, 66) argues: ‘the question [of heritage] is not “what?” as much as “what for?”’, which raises further questions of authenticity and cultural significance. Physical landscapes, cultural space, and questions of motivation and significance all inform the construction of something that is considered ‘authentic’ or ‘representative’ by the different people who are interacting with the past. Jackson (2009) expresses a similar holistic conception of heritage, as she describes it as both space and place, physical and social, where identities intersect. This conception allows us to consider the effects of a particular place and tangible landscape on the development of the ideas that come to form ‘heritage knowledge’.

When considering what constitutes health as it relates to embodied practice, it is critical to look to what is currently manifested in everyday life. Any understanding of the past starts from the present. It is from this point that we can begin to observe the distinct factors that have led to the construction of the past in any particular situation (Olwig 1999). Lowenthal (2005, 82) discusses this connection explicitly, describing the past as a foreign realm that is ‘suffused by the present’. Trouillot (1995, 27) echoes this idea, noting that any narration of the past is a ‘particular bundle of silences’ that are ‘the result of a unique process’, and stating that ‘the operation to deconstruct these silences will vary accordingly’. We must carefully look through the present to uncover the ‘authentic’ past, however it becomes defined.

There is, of course, a fundamental epistemological problem underlying attempts to accomplish this. Lowenthal (1985) outlines this problem by noting that each account of the past is ‘both more and less than the past’ (xxii), and explaining that no account can ‘incorporate an entire past’ and that every account is told by a narrator who has ‘the advantage of knowing subsequent outcomes’ (xxiii). This insight lends itself to a call for careful ethnographic research in local communities to determine which aspects of heritage remain salient, and how so, among community members in the present. Adding complexity to this discussion is disagreement about how ‘salient’ is defined and for what purpose. ‘Contested’ or ‘constructed’ heritage conversations, such as those that become politicized, such as the recent Maya Land Rights case (see Campbell and Anaya 2008), both critique community definitions of their own heritage and those definitions imposed on them by others, including governmental bodies (Piotrowski 2012; Medina 1998).

Ironically, relatively new interest in the overlap between environmental and cultural heritage by global organizations like UNESCO seems to have had an opposite effect on the way environmental knowledge is defined as heritage. In order to meet certain criteria, local aspects of environmental heritage are removed and the fluidity of heritage for individuals and communities may be lost. Just as most current definitions of ‘health’ perpetuate a standardized, biomedical view of physical health, the current definition of World Heritage refers exclusively to natural phenomena, which are ‘stripped of their actual cultural, social and political meanings and neatly placed into an already existing administrative context’ (Krauss 2005, 44), thus reinforcing a static conception of heritage. As the following case study shows, using ethnographic research to consider embodied experience can counter this trend and bring both individual and social experience to light.

Case Study: Belize

We have to teach our children the correct way for our life. When we are a baby, we eat käla, tutu [jippy jappa palm, fresh water snails]. It’s not like chemicals. We never had a stomachache because our parents serve us the best food – no chemicals.

– Julio Canti, Santa Cruz, Belize, 2011

The Mopan Maya community of Santa Cruz, located in the lowland rainforest of the Toledo district of Belize, balances tradition and change through daily practice. Primarily a subsistence farming community practicing rotating cultivation, they collectively manage community lands. Community leaders have articulated the importance of this traditional practice in a recent land rights case, which has received international attention (Campbell and Anaya 2008). I conducted twelve months of ethnographic research in this community, which culminated with my administering a survey that assessed environmental heritage and wellness. This survey measured the degree to which families participated in activities that were described by community members as either ‘healthy’ or as important for their heritage or ‘being Maya’, a phrase often used when community members discussed traditions they classified as critical to a happy and healthy life. Administered in sixty-four households, the survey supported other ethnographic findings by showing connections between participating in heritage activities and being healthy (Baines 2016b). Here, I describe how some of these connections were demonstrated ethnographically in order to illustrate how the EEH framework might be useful for understanding and measuring health in a more holistic way. (A more detailed ethnographic account of this case can be found in Baines 2016a.)

In Santa Cruz, traditional social and ecological practices, such as planting corn, exchanging labor in traditional house-building practices (known as usk’inak’in or ‘a day for a day’), and harvesting wild plants, were found to have deep connections to the physical body and, ultimately, to health. Community members’ narratives linked illness and unhappiness to not practicing such traditions. For example, diabetes, which is found with increasing frequency in rural Belize, was attributed to increased consumption of processed food and to a lack of patience for the more time-consuming traditional food practices. They explained that white flour tortillas are easier to process and produce, and that they are too ‘lazy’ (meaning impatient) to wait for the local, corn-fed chickens to fatten, preferring instead to consume ‘white’ chickens that are raised on store-bought feed. In these examples, mental health (happiness), physical health (diabetes), Maya heritage practices (growing and processing corn with others), local ecological knowledge (raising chickens) and moral valuations (impatience, or laziness) converge to assess health.

The sweat and dirt associated with work in the forest were found to be closely associated with strength and wellness. Again, the valuation of doing the work of planting and processing corn, harvesting wild plants, and hunting exemplifies the intersection of holistic health and heritage. The negative ramifications of a person’s inability to do such work were perhaps most clearly exemplified in discussions about school. The high costs of high school, for example, were associated with changes in work and social practices, causing families to seek extra cash by taking employment outside of the community or making crafts to sell to visitors. Children who left the village to attend high school were unable to access their traditional foods while at school, and were sometimes unable to participate in social and economic activities back in the village (Baines and Zarger 2017). The increased numbers of children attending high school and the concomitant declining participation in heritage practices was worrisome to those concerned with these children having access to a ‘good, Maya life’.

Community members’ definitions of ‘being Maya’ and doing what Maya people do extended to all aspects of health and wellness. The laughter associated with playing games late into the night (with those who would help you plant corn in the morning) fueled discussions of happiness. The social relationships and traditional labor exchange system needed to build a thatch house in a short window of time were just as important in a person’s choice of a thatch house over a cement house as the fact that thatch houses are cooler. Throughout my ethnographic data collection, I found that the physical was wound closely to the social, and ecological heritage practices were bound to a good or happy life. It is critical to remember that such practices are not frozen in time nor wholly prescriptive but defined through everyday activities, forming a kind of fluid heritage carried in the body. Life in Santa Cruz is fluid, changing with people’s engagements with the court system, the paving of the road, the ubiquity of high school education, and the effects of global climate shifts. Health, as defined by community members, is explicitly linked to how these lives are lived, through everyday practices as part of their physical, mental, and social lives.

How a physical practice is intricately tied to both health and heritage is complex and fluid in one sense but straightforward in another. I have encapsulated extensive ethnographic data in a series of what I call ‘phenomenological processing loops’ to illustrate how, in the case of the community of Santa Cruz, the body is the place where ecology, heritage, and health come together through practice. It is important to remember that heritage practices are part of ‘being Maya’ and thus carry with them moral valuations. As one community member stated, ‘taking care of the forest is a Maya value’.

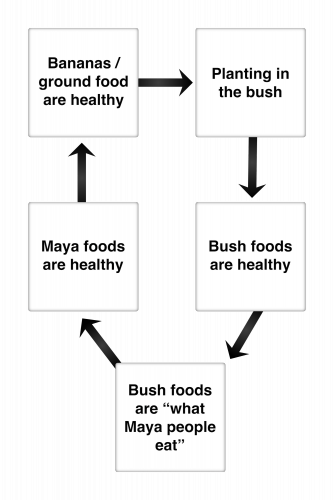

Figure 1 shows how bananas, a food considered healthy within biomedicine for its mineral content (among other properties), are considered healthy among Maya because they are deemed a heritage food. Beginning at the middle right of the loop, wild foods harvested from ‘the bush’ or forest are considered to be healthy, and therefore the process of harvesting and eating them embodies healthy practice. Following the arrows, this process of harvesting and eating bush foods is linked to Maya identity: it is a heritage practice. ‘Being Maya’ and eating Maya foods is linked to health. The traditional ecological practice of planting in the bush is linked to Maya identity. If bananas are planted in the bush, even though they are a domesticated plant, they become healthy because of both their location and that location’s relationship to Maya identity. Thus, a banana, a food associated with physical health in a biomedical sense, is ‘actually’ healthy in a holistic sense, if we understand ecological heritage practices as linked to health through the fluidity of what constitutes heritage.

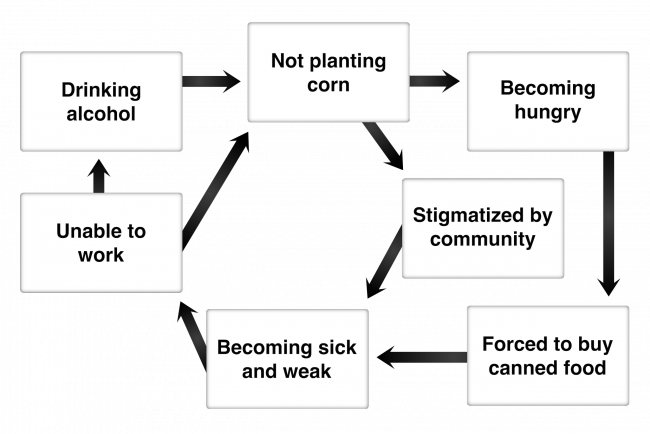

Figure 2 shows how alcohol consumption is considered an unhealthy practice in the frame of embodied ecological heritage, as the unhealthy physiological, mental, and moral aspects of drinking alcohol are closely tied to an absence of ecological heritage practices. Planting corn is arguably the practice most critical to ‘being Maya’ and leading ‘a healthy Maya life’, and not doing so has implications on every level. From a biomedical perspective, alcohol consumption is unhealthy because of its toxic effects on the liver. When viewed through the EEH frame, however, we can see that drinking alcohol prevents the embodiment of this critical ecological heritage practice. While Maya understand that eating canned or processed food can have detrimental physiological effects, they also see health problems arising when a man does not provide corn for the family.

Figure 2. Phenomenological processing loop: Alcohol as unhealthy (original version printed in Baines 2011, reprinted in Baines 2016)

Figure 2. Phenomenological processing loop: Alcohol as unhealthy (original version printed in Baines 2011, reprinted in Baines 2016)The fundamental connections represented in these phenomenological processing loops are deeply informed by ethnographic research and have broad implications for health understandings, both in theory and in application. Maya communities in Belize, like many indigenous communities around the world, face threats from national and international forces seeking access to and control over their traditional lands. Understanding embodied ecological heritage and its relation to holistic conceptions of health and well-being is essential for fully appreciating and countering such threats.

Case Study: New York City

They don’t have the proper nourishment. It’s not like back when we were young – [now] the parents give them box food and apple juice.

– Winston Williams, Bronx, New York, 2016

New York City is home to hundreds of immigrant communities hailing from all parts of the world, and the health of these individuals and communities is a priority of many different organizations. While considering the question of how we seek and provide evidence for health, I began to notice practices amongst my neighbors that might be understood as everyday embodiments of ecological heritage. The connections between ecological heritage practices and health in Maya communities seemed to speak to the utility of the EEH framework, leading me to wonder if the same framework could help me understand and demonstrate health in other communities. Could I show that heritage and its links to health were carried in the body from one environment to another?

To investigate the idea that heritage is carried in the body through practice, I began to conduct ethnographic research in Caribbean and Latin American immigrant households in New York City. From preparing traditional meals to picking wild plants in local parks, the research participants continued to practice ecological traditions after moving to the city, and they assured me that doing so kept them healthy. In our discussions they commonly emphasized that there is a strength that comes with these traditional practices; this strength is simultaneously physical because the foods are not processed, social because the family comes together to help with the labor, and mental because it requires one to slow down and relax to participate. The following, again, is a brief summary of a larger ethnographic project (Baines forthcoming), which I present for the purpose of considering how the EEH framework may contribute to the study of immigrant health.

In contrast to the implicit assumption that immigrants are healthier if they assimilate and access biomedical health care (Viruell-Fuentes et al. 2012), the EEH framework allows for an exploration of health as it is defined holistically by immigrants themselves. Linking specific everyday embodied practices to the maintenance of health goes some distance to counter arguments that posit biomedical health knowledge as more ‘developed’ or more effective, with the latter claim effectively challenged from the perspective of alternative medical systems (Murquia, Peterson, and Zea 2003). Doing so highlights the social piece of the EEH framework, as many of the practices are supported within immigrant social networks. It does this while still focusing on the specific practice and on the body as the locus of heritage, rather than the mind or the memory.

Immigrant families whose members (oftentimes elders) had continued a practice after their move to New York City spoke about how they felt ‘stronger’ when they prepared meals in the same way they had in previous environments. One example involves the preparation of hadutu, a traditional soup prepared by Garifuna communities hailing from the coastal areas of Honduras and Belize. The labor involved in grating the coconut using traditional tools was both a reinforcement of and a testament to that strength. Preparing food that was considered healthy was linked to both the social component (it took a lot of people to get it done) and the issue of time (everyone is so busy in the city). When participants spoke about the long time spent together to make traditional food they also expressed respect for both elders and the traditional ingredients. Amongst Garifuna and other communities, discussions of preservatives and chemicals in convenience foods were almost always intertwined with discussions of patience and anticipation, joy and togetherness. Such evidence of how ‘culinary care’ (Yates-Doerr and Carney 2016) can positively impact health is mounting, referencing environmental and social forces and solidified through these tangible embodied experiences related to cooking.

Embodied ecological heritage: A discussion of knowledge and practice

The ecological body as heritage might be thought of as a way of getting at an intersection of the classic theoretical concepts of habitus and embodiment.

– Kristina Baines, ‘Loops of Knowledge Shared’

Taken up and outlined most explicitly by Bourdieu (1977), ‘habitus’ describes how bodily learning takes place, in a sense, without the conscious cognition typically understood to accompany the learning process. Embodied activity, Crossley (1996, 99) explains, ‘takes up these habitual schema and deploys them, in situ, with competence and skill’. This is what I hope using the EEH framework in ethnographic work will capture. Essentially, knowledge and practice come together through physical application. A consideration of environmental knowledge and practice in this framework allows for a more fluid understanding of both the biological and the social, and pushes beyond existing theoretical and operational divides. Through an ethnographic study of human/environment interactions, the EEH framework seeks to flesh out what is essentially a ‘cognitive phenomenology’, something that, in the past, would likely have been described as an oxymoron.

Lauer and Aswani (2009, 318) problematize the word ‘knowledge’ and ‘its root in questionable epistemological assumptions of abstraction, formality and articulation’. This critique is especially salient in many indigenous and immigrant communities, including those referenced here, where learning more typically happens ‘in situ’ or in practice (Zarger 2009), as opposed to in a formal way. In my research in Santa Cruz, participants often spoke of learning with phrases like ‘I remember it because we used to do it when I was young’ rather than ‘I was taught it’. The transmission of abstract knowledge without foundation in practice, particularly knowledge related to tradition or heritage, was rarely observed or discussed.

Understanding how people think about their experience of health through their everyday ecological practices, I argue, is key to truly moving – both theoretically and practically – beyond dichotomous notions of health, which emphasize physiological measures. Conceptualizing the body in multiple ways, in terms of the individual, social, and political (Scheper-Hughes and Lock 1987), offers a starting point to this understanding. It is, however, limited as far as conceptualizing how people learn and acquire this knowledge in their day-to-day lives. This limitation is particularly important when considering that ‘traditional’ knowledge is seen as ‘intricately bound to the experiential process’ (Bates et al. 2009, 128) in contrast to the more abstract acquisition of knowledge associated with market economies. In response to this limitation, Hsu (2007) proposes a fourth way of conceptualizing the body, which she calls the ‘body ecologic’. Her concept not only offers a way of ‘investigating contemporary body concepts that ultimately are derived from ecological experiences’ (Hsu 2007, 92), but also a tool for understanding how embodied knowledge gained from environmental experience informs perceptions of health, as considered by both subjective and objective measures. This promising model is, however, in need of development. While Hsu’s (2007, 92) primary use for the body ecologic model is to ‘unravel … complex histories’, the discussion presented here provides an opportunity to operationalize this theory beyond historical analysis and apply it to embodied ecological heritage. Explicitly adding a discussion of the physical body to discussions of ‘intangible’ or ‘natural’ heritage (Graham 2002; Lowenthal 2005) is a critical component of this operationalization.

Ingold’s ‘enskillment’ model has both theoretical and practical overlap with the ideas presented by Hsu, as both emphasize that people respond in a flexible and changeable way to environmental information that they experientially learn. However, neither clearly theorizes how ecological skill actually acts on biology or provides a clear mechanism for understanding how the wellness of an individual or a community is practically affected by the process of becoming enskilled through ecological knowledge. With the EEH framework, I hope to take the next step in advancing this theory, giving ethnographers working at the health/environment intersection another tool to draw on to provide evidence to answer the question: ‘But are they actually healthier?’

Are they actually healthier? A conclusion

The answer is ‘yes’. Despite our best efforts to extract ourselves from the dualism and dichotomous thinking of our everyday lives, our notion of physical bodily health being the ‘real’ or ‘actual’ kind of health consistently bubbles up. But extensive ethnography and the EEH framework enable us to focus on the body with an active consideration of the social and ecological context in which it operates. We cannot extract the body from its environmental and social circumstances, but that does not mean that it can only be understood from those external perspectives. Embodied practice changes the body on a level that is tangible. Deviating from the Maya heritage practice of eating local chicken and corn tortillas is both deemed negatively and is likely to increase the prevalence of diabetes (as noted by community members and supported by biomedical knowledge). Similarly, picking wild plants in New York City parks to make traditional dishes is both social, in that it involves being with family in a natural space, and physical, in that the nutrients the plants provide are not found in processed foods that are more easily accessed. In both cases, the physical and the social are interwoven in ecological heritage practice.

Arguably one of the greatest contributions of anthropology to the understanding of health is its ability to truly integrate the social and environmental into a holistic discussion. I argue that we have never shied away from the knowledge that this holism leads to more effective action and, hopefully, better outcomes for the communities we work with. In a time when the ‘management of packaged knowledge stripped of its lived context, meaning, and interpretation’ is the norm, the value of holism needs to be consistently reasserted, its power as evidence clearly stated amidst global changes (Wilkinson and Kleinman 2016, x). Placing the lived experience of the body in context through detailed ethnographic study, it is my argument and my hope, moves beyond decontextualized physical measures in a real way. Ethnography can uncover the nuanced way that heritage becomes contextualized and embodied through ecological practices, and how such practices relate to healthy bodies and healthy communities. Pushing the theoretical framework for understanding health in a holistic way beyond the physical/social divide, EEH is a tool to guide this work. Dichotomous views of health are part of our living medical anthropological heritage. Perhaps challenging this heritage through embodied ethnographic research is the key to improving our understanding of health, both in ourselves as well as in the communities we work alongside.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the community members in southern Belize and New York City who continue to generously share their time and thoughts with me. I would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers whose comments were invaluable in helping me clarify and strengthen my argument. I am very grateful to Erin Martineau and the editors at MAT for their detailed and thoughtful work on the manuscript. I would also like to thank Becky Zarger and Victoria Costa for their valuable comments and conversations around early versions of this article.

About the author

Kristina Baines is a sociocultural anthropologist with an applied medical/environmental focus. Her research interests include indigenous ecologies, health, and heritage in the context of global change, in addition to publicly engaged research and dissemination practices. She is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the City University of New York, Guttman Community College, and the Director of Anthropology for Cool Anthropology.

References

Adelson, Naomi. 2009. ‘The Shifting Landscape of Cree Well-Being’. In Pursuits of Happiness: Well-being in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Gordon Mathews and Carolina Izquierdo, 109–23. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Arquette, Mary, Maxine Cole, Katsi Cook, Brenda LaFrance, Margaret Peters, James Ransom, Elvera Sargent, Vivian Smoke, and Arlene Stairs. 2002. ‘Holistic Risk-based Environmental Decision Making: A Native Perspective’. Environmental Health Perspectives 110 (Suppl 2): 259–64. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.02110s2259.

Atleo, Marlene. 2008. ‘From Praxis to Policy and Back Again: Are There “Rules” of Knowledge Translation across Bodies/Worldviews?’ Paper presented at the University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, 15 February.

Baer, Hans A., Merrill Singer, and Ida Susser. 2003. Medical Anthropology and the World System. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Baines, Kristina. 2011. ‘Loops of Knowledge Shared: Embodied Ecological Heritage in Southern Belize’. In Sharing Cultures, edited by Sergio Lira, Rogerio Amoeda, and Cristina Pinheiro, 301–09. Lisbon: Green Lines Institute for Sustainable Development.

Baines, Kristina. 2016a. Embodying Ecological Heritage in a Maya Community: Health, Happiness, and Identity. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Baines, Kristina. 2016b. ‘The Environmental Heritage and Wellness Assessment: Applying Quantitative Techniques to Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Wellness Relationships’. Journal of Ecological Anthropology 18 (1). https://doi.org/10.5038/2162-4593.18.1.4.

Baines, Kristina. Forthcoming. ‘Narrating Ecological Heritage Practices for Cross-Generational Wellness’. In Narrating Perspectives in Childhood and Adolescence, edited by Mery Diaz and Benjamin Shepherd. New York: Columbia University Press.

Baines, Kristina, and Rebecca Zarger. 2017. ‘“It’s Good to Learn about the Plants”: Promoting Social Justice and Community Health through the Development of a Maya Environmental and Cultural Heritage Curriculum in Southern Belize’. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 7 (3): 416–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-016-0416-3.

Bates, Peter, Moe Chiba, Sabina Kube, and Douglas Nakashima, eds. 2009. Learning and Knowing in Indigenous Societies Today. Paris: UNESCO.

Baumflek, Michelle, Stephen DeGloria, and Karim-Aly Kassam. 2015. ‘Habitat Modeling for Health Sovereignty: Increasing Indigenous Access to Medicinal Plants in Northern Maine, USA’. Applied Geography. 56: 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.10.012.

Blake, Kevin S. 2002. ‘Colorado Fourteeners and the Nature of Place Identity’. Geographical Review 92 (2): 155–79.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bruhn, John G., David Cordova, James A. Williams, and Raymond J. Fuentes. 1977. ‘The Wellness Process’. Journal of Community Health 2 (3): 209–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01349705.

Campbell, Maia S., and S. James Anaya. 2008. ‘The Case of the Maya Villages of Belize: Reversing the Trend of Government Neglect to Secure Indigenous Land Rights’. Human Rights Law Review 8 (2): 377–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngn005.

Chan, Selina Ching. 2005. ‘Temple-Building and Heritage in China’. Ethnology 44 (1): 65–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773960.

Crossley, Nick. 1996. ‘Body-Subject/Body-Power: Agency, Inscription and Control in Foucault and Merleau-Ponty’. Body and Society 2 (99): 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034x96002002006.

Csordas, Thomas. J. 1994. Embodiment and Experience: The Existential Ground of Culture and Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donatuto, Jamie, Larry Campbell, and Robin Gregory. 2016. ‘Developing Responsive Indicators of Indigenous Community Health’. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13 (9): 899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13090899.

Donovan, Robert J. 1995. ‘Steps in Planning and Developing Health Communication Campaigns: A Comment on CDC’s Framework for Health Communication’. Public Health Reports (1974-) 110 (2): 215–17.

Dove, Michael. 2007. ‘Indigenous People and Environmental Politics’. Annual Review of Anthropology 35: 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123235.

Foucault, Michel. 1973. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. New York: Routledge.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books.

Good, Byron. 1993. Medicine, Rationality and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graham, Brian. 2002. ‘Heritage as Knowledge: Capital or Culture?’ Urban Studies 39 (5-6): 1003–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220128426.

Harvey, T. S. 2008. ‘Where There Is No Patient: An Anthropological Treatment of a Biomedical Category’. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 32 (4): 577–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-008-9107-1.

Healey-Ogden, Marion J., and Wendy J. Austin. 2011. ‘Uncovering the Lived Experience of Well-Being’. Qualitative Health Research 21 (1): 85–96.

Heidegger, Martin. 1996. Being and Time: A Translation of Sein und Zeit. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. First published in 1927.

Heil, Daniela. 2009. ‘Embodied Selves and Social Selves: Aboriginal Well-Being in Rural New South Wales, Australia’. In Pursuits of Happiness: Well-being in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Gordon Mathews and Carolina Izquierdo, 88–108. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Holmes, Seth. 2013. Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hsu, Elisabeth. 2007. ‘The Biocultural in the Cultural: The Five Agents and the Body Ecologic in Chinese Medicine’. In Holistic Anthropology: Emergence and Convergence, edited by David Parkin and Stanley J. Ulijaszek, 91–126. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Hunn, Eugene. 1982. ‘The Utilitarian Factor in Folk Biological Classification’. American Anthropologist 84 (4): 830–47. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1982.84.4.02a00070.

Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge

Ingold, Tim. 2007. ‘Movement, Knowledge and Description’. In Holistic Anthropology: Emergence and Convergence, edited by David Parkin and Stanley J. Ulijaszek, 194–211. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

International Council for Science. 2002. Science, Traditional Knowledge and Sustainable Development. Paris: UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001505/150501eo.pdf.

Ito, Karen. 1999. ‘Health Culture and the Clinical Encounter: Vietnamese Refugees’ Responses to Preventative Drug Treatment of Inactive Tuberculosis’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 13 (3): 338–64. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1999.13.3.338.

Jackson, Antoinette. 2009. ‘Conducting Heritage Research and Practicing Heritage Resource Management on a Community Level: Negotiating Contested Historicity’. Practicing Anthropology 31 (3): 5–10.

King, Ursula, and Christopher Furgal. 2014. ‘Is Hunting Still Healthy? Understanding the Interrelationships between Indigenous Participation in Land-Based Practices and Human-Environmental Health’. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11 (6): 5751–82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110605751.

Kleinman, Arthur. 1989. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition. New York: Basic Books.

Krauss, Werner. 2005. ‘The Natural and Cultural Landscape Heritage of Northern Friesland’. International Journal of Heritage Studies 11 (1): 39–52.

Lauer, Matthew, and Shankar Aswani. 2009. ‘Indigenous Ecological Knowledge as Situated Practices: Understanding Fishers’ Knowledge in the Western Solomon Islands’. American Anthropologist 111 (3): 317–29.

Levin, Betty Wolder, and Carole H. Browner. 2005. ‘The Social Production of Health: Critical Contributions from Evolutionary, Biological, and Cultural Anthropology’. Social Science & Medicine 61 (4): 745–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.048.

Lock, Margaret. 1993. ‘Cultivating the Body: Anthropology and Epistemologies of Bodily Practice and Knowledge’. Annual Review of Anthropology 22 (1): 133–55.

Lowenthal, David. 1985. The Past Is Another Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lowenthal, David. 2005. ‘Natural and Cultural Heritage’. International Journal of Heritage Studies 1 (1): 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250500037088.

Mackey, Sandra. 2009. ‘Towards an Ontological Theory of Wellness: A Discussion of Conceptual Foundations and Implications for Nursing’. Nursing Philosophy: An International Journal for Healthcare Professionals 10 (2): 103–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-769x.2008.00390.x.

Mark, Glenis Tabetha, and Antonia C. Lyons. 2010. ‘Maori Healers’ Views on Wellbeing: The Importance of Mind, Body, Spirit, Family and Land’. Social Science & Medicine 70 (11): 1756–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.001.

McKercher, Bob, and Hilary D. Cros. 2002. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Hospitality Press.

Medina, Laurie K. 1998. ‘History, Culture, and Place-Making: “Native” Status and Maya Identity in Belize’. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 4 (1): 134–65. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlca.1998.4.1.134.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. (1962) 2002. The Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge.

Moustakas, Clark. 1994. Phenomenological Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Murquia, Alejandro, Rolf A. Peterson, and Maria Ceclia Zea. 2003. ‘Use and Implications of Ethnomedical Healthcare Approaches among Central American Immigrants’. Health and Social Work 28 (1): 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/28.1.43.

Nazarea, Virginia D. 1999. Ethnoecology: Situated Knowledge/Located Lives. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Olwig, Karen Fog. 1999. ‘The Burden of Heritage: Claiming a Place for a West Indian Culture’. American Ethnologist 26 (2): 370–88. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1999.26.2.370.

Parlee, Brenda, Fikret Berkes, and Gwich’in People. 2005. ‘Health of the Land, Health of the People: A Case Study on Gwich’in Berry Harvesting in Northern Canada’. EcoHealth 2 (2): 127–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-005-3870-z.

Pierotti, Raymond, and Daniel Wildcat. 2000. ‘Traditional Ecological Knowledge: The Third Alternative (Commentary)’. Ecological Applications 10 (5): 1333–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/2641289.

Piotrowski, Silas. 2012. ‘Contested Heritage, Contested Aboriginality and the Blue Tier, Northeast’. Australian Archaeology 74: 115–16.

Posey, Darrell A., John Frechione, John Eddins, Luiz Francelino Da Silva, Debbie Myers, Diane Case, and Peter Macbeath. 1984. ‘Ethnoecology as Applied Anthropology in Amazonian Development’. Human Organization 43 (2): 95–107. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.43.2.908kp82611x0w860.

Reeve, Mary-Elizabeth. 2000. ‘Concepts of Illness and Treatment Practice in a Caboclo Community of the Lower Amazon’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 14 (1): 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2000.14.1.96.

Reyes-García, Victoria, Vincent Vadez, Susan Tanner, Thomas McDade, Tomás Huanca, and William R. Leonard. 2006. ‘Evaluating Indices of Traditional Ecological Knowledge: A Methodological Contribution’. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2 (1): 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-2-21.

Ross, Norbert. 2002. ‘Cognitive Aspects of Intergenerational Change: Mental Models, Cultural Change, and Environmental Behavior among the Lacandon Maya of Southern Mexico’. Human Organization 61 (2): 125–38. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.61.2.9bhqghxvpfh2qebc.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy, and Margaret Lock. 1987. ‘The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1(1): 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1987.1.1.02a00020.

Setten, Gunhild. 2005. ‘Farming the Heritage: On the Production and Construction of a Personaland Practised Landscape Heritage’. International Journal of Heritage Studies 11 (1):67–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250500037054.

Stephenson, Jr., David J. 1999. ‘A Practical Primer on Intellectual Property Rights in a Contemporary Ethnoecological Context’. In Ethnoecology: Situated Knowledge/Located Lives, edited by Virginia D. Nazarea, 230–48. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Tangenberg, Kathleen M., and Susan Kemp. 2002. ‘Embodied Practice: Claiming the Body’s Experience, Agency and Knowledge for Social Work’. Social Work 47 (1): 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/47.1.9.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.

Viruell-Fuentes, Edna A., Patricia Y. Miranda, and Sawsan Abdulrahim. 2012. ‘More than Culture: Structural Racism, Intersectionality Theory, and Immigrant Health’. Social Science & Medicine 75 (12): 2099–2106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037.

Walsh, Michael J. 2007. ‘Efficacious Surroundings: Temple Space and Buddhist Well-being’. Journal of Religion and Health 46 (4): 471–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-007-9129-y.

Wilkinson, Ian, and Arthur Kleinman. 2016. A Passion for Society: How We Think about Human Suffering. Oakland: University of California Press.

Wojnar, Danuta M., and Kristen M. Swanson. 2007. ‘Phenomenology: An Exploration’. Journal of Holistic Nursing 25 (3): 172–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010106295172.

Wolverton, Steve, Justin M. Nolan, and Matthew Fry. 2016. ‘Political Ecology and Ethnobiology’. In Introduction to Ethnobiology, edited by Ulysses Paulino Albuquerque, and Rômulo Romeu Nóbrega Alves, 75–82. Cham: Springer.

World Health Organization. 1946. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19–22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948.

Yates-Doerr, Emily, and Megan A. Carney. 2016. ‘Demedicalizing Health: The Kitchen as a Site of Care’. Medical Anthropology 35 (4): 305–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2015.1030402

Zarger, Rebecca K. 2009. ‘Learning the Environment’. In The Anthropology of Learning in Childhood, edited by David Lancy, John Bock, and Suzanna Gaskins, 341–69. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Endnotes

1 Back

More extensive ethnographies of the cases discussed in this article can be found here: Baines (2016a, forthcoming).

2 Back

The phenomenological paradigm has a broad philosophical base with its anthropological manifestation taking its cue from Heidegger’s (1996) hermeneutic philosophy of ‘in-der-Welt-sein’ or ‘being-in-the-world’ as it was taken up in Merleau-Ponty’s ([1962] 2002) discussion of the ‘lived body’, which embodies practical behavior.

3 Back

See also Baines (2016a, 2016b, 2017) on Maya communities in Belize and Baines (forthcoming) on Latin American and Caribbean immigrant communities in New York City.