Death poems for Cindy

—

There are some research participants whom we never forget. For me, it is a woman I’ll call ‘Cindy’.

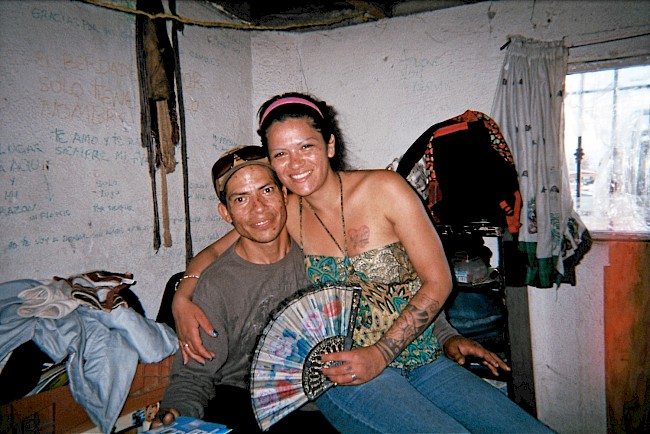

I initially met Cindy in the project office of an HIV study that I helped coordinate in Tijuana’s famous Red Light District. Cindy and her partner, whom I’ll call ‘Beto’, became a central part of my research on how love and emotional intimacy shape health and well-being among female sex workers who inject drugs and their intimate, noncommercial male partners. Drawing on three years of ethnographic fieldwork, in-depth interviews, and a photovoice project in which couples were given cameras to document their relationships, this research challenges pathologized notions of sex workers’ relationships as merely sites of risk and violence. I conceptualize sex workers’ intimate relationships as ‘dangerous safe havens’ that provide emotional refuge and solidarity against a world of inequality (Syvertsen and Bazzi 2015). In these relationships, classic epidemiological ‘risk behaviors’, such as having unprotected sex and sharing syringes, are reinterpreted as meaningful forms of emotional commitment and care despite their potential for real physical harm.

Over the course of the project, Cindy and Beto increasingly opened up and invited me into their dangerous safe haven. They shared candid stories about their experiences and allowed me to gain insight into their daily lives. I came to know Cindy as smart and funny, as well as a survivor of multiple traumas, a deportee with an arrest record, a sex worker addicted to heroin, and a caring partner deeply in love with Beto. Cindy’s relationship with Beto had a far more meaningful impact on her daily life than something that could be glossed as a source of ‘risk’, and her experiences were too complex to be reduced to clinical HIV intervention strategies.

Cindy was born in Mexico and smuggled into the United States when she was young. She openly sobbed when recounting her experiences of childhood sexual abuse and feelings of abandonment, which first prompted her experimentation with drugs as a teenager. Later, a bad marriage exposed her to heroin, and eventually her addiction escalated such that she began selling heroin to maintain her use. Cindy was later deported to Tijuana where heroin was especially plentiful and cheap, and, like growing numbers of displaced women along the border, sex work provided a quasi-legal opportunity to support herself in the informal economy. Life in Tijuana also exposed her to new forms of violence and insecurity, which intensified her vulnerability to HIV and other health harms. However, when Cindy met her partner Beto while waiting to score heroin one day, her life changed. Born and raised in Tijuana, Beto also suffered from what he called the ‘emotional disease’ of addiction, which he attributed to a difficult childhood. As adults, they finally found in each other a sense of belonging through their shared struggles. Cindy always spoke of Beto with admiration, and their interactions as a couple were playful and affectionate. Coming together amidst their shared histories of trauma, heroin addictions, and struggles to survive on the margins of Tijuana rendered their love and care for each other all the more vital in their lives.

Some time after my research ended, I learned that Cindy passed away. She had been periodically ill throughout my fieldwork with undetermined flu-like symptoms, but I was unaware of the seriousness of her condition. Even though it was years later, finding out about her passing was devastating. I wanted to reconcile my very personal and emotional reaction to her senseless death with the intellectual sense-making that I’ve tried to craft of her life. But I needed a new way of understanding.

Death and mourning jar us out of the mundane demands of our work, taking us back to what really matters in the anthropological pursuit: the difficult, often bewildering, emotionally taxing, and humanistic passion to understand the diversity of life that only comes by building meaningful relationships in the field. Reflecting on the death of a study participant also invites bigger questions for anthropologists to consider: What new ways of knowing open up when we re-examine our data and consider how to represent the deceased? Can reflecting on a single life help illuminate the collective experiences of those who are too often forgotten? How can a tragic death reinvigorate an anthropological commitment to pursue the difficult work that really matters?

In reflecting on Cindy’s death, new forms of meaning arose from her life, inspiring me to continue to challenge largely sanitized and dispassionate scholarly depictions of sex work and HIV risk. Both her life and her death made clear that, even amidst conditions of inequality and material deprivation, individuals try to build meaningful lives through emotional connection. Although Cindy’s love for Beto could not ultimately protect her from the cumulative disadvantage that led to her early death, her entire life experience cannot be reduced to meaningless suffering.

Openings

Rather than mourn Cindy’s death as an ending, I want to reframe it as an opening. Following Glesne (1997), the absence of neat conclusions to my work with Cindy, reflective of the messiness of anthropological research more generally, invites an ‘opening’ to use experimental forms of analysis, interpretation, and writing as ways to commemorate life. ‘In this opening’, Glesne (1997, 218) writes, ‘light shines on interconnections among researcher and participants. Readers are invited to join in, not only with critique, but also with their feelings and personal reflections. The clearing ruptures traditional patterns of scientific knowing and notions of research purposes’. Experimental mediums offer a particularly important outlet to explore ultimately unknowable human questions of life and death.

Photography and poetry open spaces for creativity and emotional experience that can produce new modes of reflection in the world, and I use both here to honor a life. Photography can humanize and reframe understandings of stigmatized lives. Many of the photos in this essay are taken by Cindy or Beto as part of their photovoice project; others were taken by a colleague or me during fieldwork with the couple. Poetry cuts to the essence of what is important. My approach takes a liberal interpretation of Japanese death poetry, in which the writer is close to death and writes poems for family and friends about their life. The quoted text in the poems is taken from interview transcripts with Cindy, whose English-Spanish code-switching responses are used as a form of ‘found data poetry’ (Janesick 2015) to integrate her own voice into poems about her life. This approach is especially appropriate because, even though she was unable to finish high school, literature was Cindy’s favorite subject: ‘I love literature; I love writing, reading, poetry, and writing poems, short stories – I love it’, she once told me.

Ultimately, this experimental work contributes to anthropological conversations about the ethics and aesthetics of representing marginalized lives. It also honors what it means to love and care in contexts of structural violence, social exclusion, and illness.

1. Sun setting in Cindy and Beto’s Tijuana neighborhood. I didn’t know that it would be the last time I ever saw Cindy. Photo by Angela Bazzi.

1. Sun setting in Cindy and Beto’s Tijuana neighborhood. I didn’t know that it would be the last time I ever saw Cindy. Photo by Angela Bazzi.Legacy

I am a person

Let me help you understand

I am more than drugs

Sex work does not define me

I am capable of love

2. Cindy looking toward her home into which she graciously invited us in; it was a single-room structure that Beto built himself. Photo by Angela Bazzi.

2. Cindy looking toward her home into which she graciously invited us in; it was a single-room structure that Beto built himself. Photo by Angela Bazzi.Dangerous safe havens

Open the doorway

To dangerous safe haven.

Where is the danger?

Outside: hurt, shame, harm, judgement

Inside: care, warmth, heroin, love

3. Beto never particularly cared for dogs, but he learned to accept Cindy’s dog Paloma and her multiple litters of puppies because it was so important to her. This was his favorite puppy, Sebu. Photo by Cindy.

3. Beto never particularly cared for dogs, but he learned to accept Cindy’s dog Paloma and her multiple litters of puppies because it was so important to her. This was his favorite puppy, Sebu. Photo by Cindy.Interspecies families

Paloma gave birth,

Something I always wanted.

‘I trust [Beto] with my dog.

I love her. She’s like my child,

and I trust him with her’.

Part of our family,

‘he loves her, he cuddles her,

… pecks the tip of her nose.

He’s not just doing it to impress me …

…it’s something born out of his heart’.

4. Contrary to stereotypes about people who use drugs as being too consumed by their addiction to care about food, Cindy loved eating and often talked about food in her interviews. This was her favorite local hamburger restaurant that evoked nostalgia for her childhood in the United States. Photo by Cindy.

4. Contrary to stereotypes about people who use drugs as being too consumed by their addiction to care about food, Cindy loved eating and often talked about food in her interviews. This was her favorite local hamburger restaurant that evoked nostalgia for her childhood in the United States. Photo by Cindy.Nourishment

‘No hay otra cosa

que quiera comer’, dijo Beto

‘Yeah! When we have extra money

he’s like, What do you want to eat?

Hamburgers, hot dogs!’

5. Within a world of constrained options, Cindy preferred to earn money through sex work rather than having Beto ‘risk himself’ by committing crimes. Beto took this photo of Cindy coming back from seeing a client because he thought she looked ‘sexy’.

5. Within a world of constrained options, Cindy preferred to earn money through sex work rather than having Beto ‘risk himself’ by committing crimes. Beto took this photo of Cindy coming back from seeing a client because he thought she looked ‘sexy’.Provision

Weighing the options

Body as economy

Agency. Asset?

‘I might just be a lady…

But I can take care of him too’.

Body to ‘borrow’

‘Hell no, a kiss is sacred!’

Reserved only for Beto

So can I have some money?

And get back to my real life.

Suffering and care

Relief from this world

Seduction of heroin

You understand me

‘Baby, your stuff is ready’

Into the dream world we go

Pain, aches, affliction.

Can’t bear to see you suffer.

Please let me help you

Through the metamorphosis.

Puncture. Grimace. Blood. Rush. Cured.

Love messages

‘Me pregunto que

tan común era la palabra “amor”?

Todavía nos

la hemos llevado a

toda madre desde el primer día’.

‘Bien enferma

Thought I was going to die…

Offered to leave him

Not because I don’t love you…

Don’t want to make your life harder’

‘But instead he said:

What are you talking about?

You’re wrong, When you’re sick

I’m going to be there for you.

…What couples are supposed to do’.

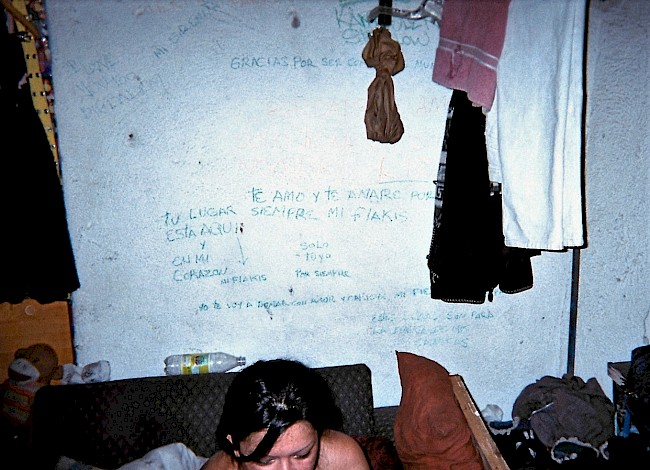

The wall, la pared

‘He wrote, “mi sirenita”

“Solo tu y yo”

“Tu lugar esta aquí”

All those messages for me’.

An exceptional destiny

‘I love my baby’

‘I trust him with all my heart, with my life…

I adore him so much’.

Even now, he makes me live

Because true love never dies…

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Cindy and Beto for generously sharing their lives with her. May Cindy rest in peace. This research was supported by NIH grants R01DA027772 and T32DA023356 and by the University of South Florida Presidential Doctoral Fellowship.

About the author

Jennifer L. Syvertsen is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Riverside. Her research is broadly concerned with addressing global health inequities and her writing aspires to humanize the experiences of socially excluded and underserved populations vulnerable to HIV, including sex workers and people who use drugs. Her interdisciplinary scholarship has appeared in such journals as Medical Anthropology, Social Science & Medicine, and International Journal of Drug Policy.

References

Glesne, Corrine. 1997. ‘That Rare Feeling: Re-Presenting Research through Poetic Transcription’. Qualitative Inquiry 3 (2): 202–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049700300204.

Janesick, Valerie J. 2016. Contemplative Qualitative Inquiry: Practicing the Zen of Research. New York: Routledge.

Syvertsen, Jennifer L., and Angela Robertson Bazzi. 2015. ‘Sex Work, Heroin Injection, and HIV Risk in Tijuana: A Love Story’. Anthropology of Consciousness 26 (2): 182–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/anoc.12037