Beyond categorical imperatives

Making up MSM in the global response to HIV and AIDS

—

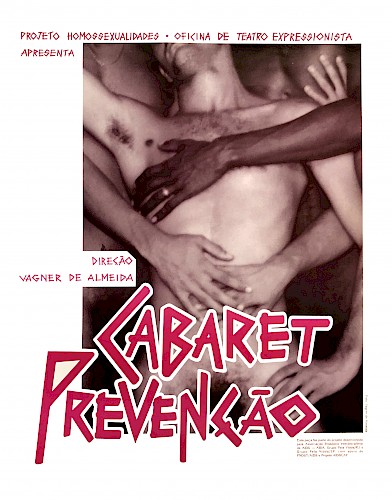

Poster for the ‘Cabaret Prevenção’ produced by the Expressionist Theater Workshop of the Projeto Homossexualidades/HSH HIV and AIDS prevention programme in Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 1995. Source: ABIA archive.

Poster for the ‘Cabaret Prevenção’ produced by the Expressionist Theater Workshop of the Projeto Homossexualidades/HSH HIV and AIDS prevention programme in Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 1995. Source: ABIA archive.In this special section of MAT focusing on ‘making up’ MSM in the field of HIV, and in global health more broadly, the guest editors and authors provide important new insights into the workings of the MSM category as it has been deployed around the world over the past three decades. Their approach moves beyond the now relatively familiar (at least to anthropologists and like-minded social researchers) critiques that have been articulated by many activists and scholars almost since the very beginning of the category. This special section thus succeeds in going beyond the predominant concern with what the category fails to do and the diversity that it at some level covers up, and moves us in the (literally) productive new direction of analysing what this peculiar category has done over the course of its history, both how it operates in the rapidly changing worlds of health and development, and how it is employed and used in a wide range of radically different contexts.

I-witnessing

Conducting the ethnographic research, like writing the history, of the MSM category is by no means an easy task, and I suspect that there may be any number of different ‘origin myths’ depending on where one is situated in the history of the epidemic. For many observers, including some of the authors whose work is brought together in this special section of MAT, the term ‘MSM’ took shape primarily as an epidemiological category, one that was initially constructed as part of an effort to describe the mechanisms responsible for the circulation of HIV in determined social networks. This is certainly what many epidemiologists themselves think. For example, in one of the lead articles of a special issue of The Lancet published some years ago, which focused exclusively on the global HIV epidemic among MSM, a distinguished group of epidemiological and biomedical researchers started their overview by staking claim to the invention of ‘MSM’ as a behavioural category that was created at a specific moment in the history of the epidemic and that had an equally specific purpose: ‘Men who have sex with men (MSM) is a term introduced in 1992 to attempt to capture a range of male–male sexual behaviours and avoid characterization of the men engaging in these behaviours by sexual orientation (homosexual, bisexual, heterosexual, or gay) or gender identity (male, female, transgender, queer)’ (Beyrer et al. 2012, 368). But as the most thorough genealogy of the term that has been written thus far, by Tom Boellstorff (2011), makes clear, versions of the phrase ‘men who have sex with men’ and its shortened acronym ‘MSM’ were in fact already beginning to circulate as early as 1988 or 1989.

Writing as someone who was an observer of many of the early discussions (hence, an I-witness, in Geertz’s [1988] sense, with the possibilities and limitations that this implies) that led to the initial production of what would later become this catch-all category, I can attest to the fact that its initial use was actually not by epidemiologists or biomedical researchers. My own memory is that as early as 1985 or 1986, social researchers were already struggling to find ways of writing about sexual practices and social relations without recourse to terms (originating in sexology and later behavioural science) such as ‘homosexual’, ‘bisexual’, and ‘heterosexual’ – precisely because we realized that the use of those terms in epidemiological discourse frequently confused descriptions of behaviour (or what we, as anthropologists, would prefer to think of as practice) with descriptions of identity (Alonso and Koreck 1989; Carrier 1989; Lancaster 1988). We also realized that self-identification, in turn, can often be far more complicated and situationally variable than what the fixed behavioural descriptors of epidemiological analysis suggest. I still remember, for example, the challenge of trying to find ways to talk about these issues as I was writing my first article on HIV and AIDS in Brazil in 1986 (Parker 1987), and the complex and often awkward linguistic constructions (‘people involved in same-sex sexual interactions’, etc.) that I tried to invent as a way around using etic linguistic categories to describe my research subjects, words they themselves would never employ and would almost certainly explicitly reject. Translating ‘experience-near’ categories from lived experience into ‘experience-distant’ categories of social analysis (to follow Geertz [1974], who was following Kohut [1971]) was never an easy task, and writing about a social field marked in profound ways by stigma and discrimination made the minefield that we seemed to be crossing especially hazardous. This was all the more the case precisely because many of us were ourselves gay-identified and/or HIV positive, and much of our work in those early years was driven not by the search for scientific certainty, but by a deep commitment to (again, quite literally) fighting for our lives and the lives of our communities. We were trying to find ways to fight back against stigma and discrimination, and to think about how our research could be employed in designing more effective community-based prevention work. We hadn’t yet invented MSM, but we knew about and felt deeply the alienation provoked by the various externally imposed categories that at the time were in use for classifying sexual others.

This early social research on sexual cultures in the context of the epidemic increasingly resonated (and was carried out in conjunction) with the experience of community health workers in gay and HIV organizations who perceived that at least some men who engaged in same-sex sexual relations didn’t identify as gay or bisexual and were not being reached by prevention programmes and materials directed to gay-identified men. The Men Who Have Sex With Men: Action in the Community (MESMAC) Project implemented in London beginning in 1990, for example, started to use the unwieldy acronym ‘MWHSWM’ (what would later morph into ‘MSM’), just as other community-based activists and researchers (like myself, working primarily in Brazil beginning in 1988) were struggling to find ways to talk about the ‘other men’ in the formulation: ‘gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men’ (Prout 1992; Prout and Deverell 1995; see also the thoughtful analysis in King 1993). We increasingly began to come into contact with one another at meetings like the annual International Conference on AIDS organized by the International AIDS Society and the short-lived but nonetheless important series of International Conferences on AIDS Education, organized primarily by the World Health Organization’s Global Programme on AIDS (WHO/GPA) in the late 1980s. (It was at the Second International Conference on AIDS Education in Yaoundé, Cameroon, in 1989, for example, that I first learned about the work of MESMAC, which was about to launch its first phase of activities.)

This interface between community-based activism and community-based research was also crucially important in a number of meetings that I had the chance to attend while working as a long-term consultant with WHO/GPA. In these gatherings, we grappled with issues of naming while at the same time beginning to build transnational networks of researchers and activists who were struggling with how to put research findings from ethnographic and observational experience into some kind of meaningful practice to prevent the spread of HIV. The first international consultation on HIV prevention for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, held in Geneva in May of 1989, for instance, brought together researchers and HIV-prevention workers from both the global North and South to discuss the challenges of reaching gay communities as well as men who have sex with men outside the context of gay communities and identities (Boellstorff 2011; McKay 2016). Over the next year, there were a number of follow-up meetings in Geneva and Amsterdam, where researchers from the University of Utrecht were collaborating with WHO/GPA to develop projects on gay and bisexual men. These meetings also offered me the chance to meet and begin to collaborate with a growing network of activist/academics – Peter Aggleton, Dennis Altman, Gary Dowsett, Michael Pollak, Theo Sandfort, and Simon Watney, to name just a few – whose work would shape my thinking for decades. These events were especially important at the time precisely because there were still no academic research centres, let alone departments, focusing on HIV or LGBT studies, and essentially no other sources of funding for research on these issues. They therefore played a key role by providing a space for developing thinking about how to address the epidemic among gay-identified men, as well as among other men who had sex with men but didn’t necessarily identify as gay (see, for example, Aggleton and Parker 2015; Boellstorff 2011; Dowsett 1989; Parker, Aggleton, and Perez-Brumer 2016; Parker, Guimarães, and Struchiner 1989; McKay 2016).

It is important to emphasize, however, that at this time, and in these contexts, the notion of men who have sex with men was never intended to serve as a kind of catch-all category that would lump together gay- or bisexual-identified men with non-gay-identified men who engaged in sex with other men (and then, even more unthinkingly, people who might later come to be classified as gender queer or as transgender women). While there was absolutely no clear consensus at the time about exactly what would be the best way to gloss/classify non-gay-identified men who have sex with men, multiple options such as MWHSWM, MSM, and other acronyms were circulating in these discussions, and the importance of finding ways to more adequately describe forms of sexual diversity were being widely debated. The option for a more all-encompassing MSM category as the most strategic option only started to take shape in the early 1990s, in part as it began to be adopted by epidemiologists to talk about what they perceived to be homosexual sex (which at the time included gender queer and transgender women, who, epidemiologically, were still being defined as engaging in male-male sex). But, in many ways, the growing use of ‘MSM’ was less because of its utility to epidemiological analyses and discourses, and more because of its strategic use in dialoguing with programme administrators, policymakers, and funders, particularly as the global response to the epidemic began to expand rapidly in the second decade of the epidemic (Parker, forthcoming).

This utility became especially clear to me in 1992, when I served briefly as chief of the Prevention Unit for the National AIDS Programme (NAP) in the Brazilian Ministry of Health. We were seeking to reorganize and restructure the NAP after a particularly gloomy period during the right-wing Collor government, and one of my own highest priorities was to find a way to expand the almost non-existent focus on prevention programmes for the gay community. One of the key arguments that a number of prominent administrators made for having ignored gay men as a focus for HIV prevention programmes was that it would heighten already existing stigma and discrimination related to ‘homosexuals’. Mobilizing leading AIDS activists (such as Herbert Daniel, Veriano Terto, Jr., and others in the emerging movement of people living with HIV) and gay rights leaders (such as Luiz Mott, among others), we countered that not developing programmes for the most affected population in the Brazilian epidemic at the time was the real expression of stigma and discrimination. We offered the ‘MSM’ category as a possible alternative to either ‘homosexuals’ or ‘bisexuals’ (the preferred terminology of the epidemiologists and the biomedical scientists in the NAP) and ‘gay’ and ‘bisexual’ (preferred by the LGBT activist community). With this wedge argument as a way through the impasse, by the time I stepped down as chief of Prevention at the end of 1992, we had managed to get MSM written into the strategic plan of the NAP, as well as to get the two major international donors (USAID, through its AIDSCAP project, and the World Bank, which had initiated negotiations for its first major loan to the Brazilian government for AIDS prevention and control, a US$250 million project that would be the first in a series of loans made over the next two decades) to build their workplans with MSM as one of the key target populations for HIV/AIDS programming at every level (Beyrer, Gauri, and Vaillancourt 2005; Parker, forthcoming) .

Following the death of my close friend and colleague Herbert Daniel, and after leaving the Ministry of Health to return to Rio de Janeiro, in 1993 I formally took on the role of executive director at ABIA, the Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association. ABIA was one of the first NGOs created in Brazil to work on HIV and AIDS, and in partnership with the Grupo Pela Vidda-Rio de Janeiro and the Grupo Pela Vidda-São Paulo (the two pre-eminent organizations led by people living with HIV) and nearly a dozen gay organizations in both Rio and São Paulo, we initiated the first large-scale, long-term intervention programme for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. We justified this programming under the MSM rubric and it was funded over the next four years primarily with resources from the AIDSCAP programme and the Ministry of Health, through the World Bank loan, along with smaller amounts from the Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and other private donors.

We consciously used the MSM label (in Portuguese, HSH) for strategic purposes, but we also explicitly varied the title of the project – at times calling it ‘Projeto HSH’, but at other times calling it ‘Projeto Homossexualidades’, in the plural – in an attempt to destabilize the notion of any single term or category as adequate for describing the sexual diversity that we were seeking to work with (Parker et al. 1995; Almeida 1997; Parker and Terto 1998). We also consciously sought to escape some of what might be described as the ‘behaviourist biases’ of international AIDS funding as it was taking shape in the mid-1990s, using funds from private donors to pay for activities focusing on cultural activism and cultural production (especially through graphic arts, theatre workshops and productions, and video production) as a way of building gay community structures and meanings through AIDS activism (Almeida 1997; Parker 2012; Parker et al. 1995; Rios et al. 2003). Using the made-up category of MSM was a strategic way of opening up spaces for responding to the epidemic among sexually and gender diverse, non-normative populations and communities.

Categorical dilemmas: MSM as practice

I could go on at greater length recounting more of my own experiences with making up MSM (especially through ABIA’s work, which continues on [Parker 2012, forthcoming]), but I have probably already abused the patience of my readers enough with this brief excursion through what many may consider ancient history. Nonetheless, I made a conscious decision to emphasize these memories precisely because they deal with a time period (the late 1980s and early to mid-1990s) and locations (Rio de Janeiro, Brasília, Geneva, etc.) that differ from those that are the primary focus of the other texts that have been brought together in this special section. Still, my own experiences and memories of living inside the epidemic during this period, and of personally grappling with the challenges and contradictions (as well as momentary satisfactions and occasional regrets) of making-up MSM over the history of the past forty years, illustrate a number of key points that I think shine through in this collection of articles as a whole.

One of the most important points that I want to make is that there is no single history or genealogy of the MSM category. On the contrary, there are probably as many histories (and origin myths) as there are people who have grappled with this category and, more importantly, with the thorny issues (epistemological, political, practical, etc.) that it opens up. This is probably true of almost all of the concepts and categories that we have devised as part of our process of inventing AIDS (Patton 1990) over the course of the past four decades. It is certainly the case with key concepts and practices such as safe (or safer) sex and harm reduction, two especially important examples precisely because, like MSM, they were initially invented not by experts, scientists, or public health specialists, but rather by members of the very communities that were most affected by the epidemic, as part of their own attempts to fight for their lives (for those who still remember the Denver Principles[note 1]). All these concepts were later appropriated by experts (especially by epidemiologists and biomedical scientists, but also, in fact, far more broadly by practitioners, programme officers, policy makers, and many others), who often got it wrong (Patton 1996) and wound up sacrificing many of the most important innovations that affected communities had frequently invented. We forget such histories only at our peril, and this is certainly one of the major reasons that we have so often wound up ‘reinventing the wheel’ over the history of the epidemic (and, sadly, in global health more broadly in the twenty-first century).

A second important point is the fact that such inventions were always flawed and, in the trenches, no matter what we might have said for external consumption, we always knew it. But we did the best we could. A key part of the history of the response to the epidemic, whether back in the 1980s and 1990s, or more recently in the 2000s and 2010s, was about trying to do what we could with symbolic and financial resources that were and continue to be limited, flawed, and compromised in so many different ways. While thoughtful recent analyses (for example, Benton 2015; Dionne 2017) have shown how AIDS exceptionalism and HIV treatment scale-up have distorted the allocation of global health resources, it is equally true that other barriers have also meant that the necessary resources have never been available. The global capitalist system within which we work and live has guaranteed that even when we have had the tools to end the epidemic, we still lack the resources we need to guarantee access to treatment and to prevention for the majority of those who need it. The ‘end of AIDS’ (Kenworthy, Thomann, and Parker 2018) has remained a remote hope, covered by a smokescreen of evasions that obscure any number of harsh realities that are in fact the direct result of the contradictions of global capitalism in the early twenty-first century. In the midst of the world of global health programmes and interventions, bureaucracies, and grassroots mobilizations that the contributors to this special section describe and analyse so thoughtfully, we are still trying to do the best we can, even as we realize how limited that often is.

A third important point that emerges as much from my own I-witnessing as from the introduction and the articles in this special section has to do with how concepts and categories (like MSM, but many others as well) travel, or, to use the language of the contributors here, how they circulate. That such categories travel geographically is unquestionably clear. Perhaps less clear is that they also travel across landscapes that are made up not only by distinct geographies but also by different economies, institutional structures, disciplines, social networks, communities, cultures, and subcultures. The paths that take them from community-based outreach projects to epidemiological presentations at international scientific conferences to the board rooms of philanthropic foundations and the corporate headquarters of the pharmaceutical industry cannot just be characterized as a simple ‘diffusion of innovations’. At every level and in all of these spaces, categories and concepts are not simply translated but in fact transformed, reinvented, reworked, and reimagined. What they mean in different contexts and to different subjects is often profoundly disparate, and this in turn may be at least one of the reasons that we so often seem to be talking past one another in so many interdisciplinary and intersectoral conversations that seek to create meaningful dialogues (especially in relation to programme and policy goals) but rarely succeed.

Finally (not because it is the last key point that might be worth making, but simply because time and space are running out), a fourth important point that runs throughout this collection of articles is just how important making up MSM has been to building the foundations of the immense ‘global AIDS industry’ that has emerged in recent decades. The idea of an AIDS industry has of course been with us for a long time (see Cindy Patton’s [1990] classic analysis of the beginnings of the AIDS industry, but also the equally insightful early work by writers such as Simon Watney [1987, 1994] and Paula Treichler [1999]). All three of the articles in this special section of MAT are masterful ethnographic portraits of key pieces of this industry as played out in specific field sites and, together with the guest editors’ introduction, they hint at the kinds of scenes and settings that might be uncovered if we were to ‘study up’ (Nader 1972; Gusterson 1997). Particularly as the juggernaut of HIV scale-up has taken shape over the course of the past two decades (Kenworthy and Parker 2014), what Patton described in 1990 as the construction of ‘victims’, volunteers’, and ‘experts’ in the AIDS service industry has of course taken on proportions that would have been unimaginable just thirty years ago, reaching the highest levels of government, becoming a primary focus of international relations and foreign aid, and involving some of the most complex (and rapacious) of capitalist industries (Big Pharma and the health care industry more generally). It is perhaps somewhat shocking to realize just how much making up MSM has been present as a focus of attention in all of these spaces, constituting one of the key building blocks used in constructing the architecture of this industry. The category of MSM has been a key part of strategic plans of international and intergovernmental agencies, a focus for the world’s largest development aid initiatives, a justification of the need for outsourcing of clinical trials funded through millions of dollars of public money, often in order to test medications patented by private industry, and so on. ‘MSM’ may be only a relatively small part of the foundation that holds up the edifice of the contemporary, twenty-first-century global AIDS industry, but it is nonetheless an important one that probably no one would have predicted just a few decades ago.

These are just a few of the insights offered by the texts in this special section of MAT on ‘making up’ MSM in relation to HIV and AIDS, and global health more broadly. By moving beyond earlier critiques of the MSM category, though still recognizing their contributions, the guest editors and the authors of the three articles included here move the field of social research on global health in important new directions. They focus less on what the MSM category fails to do and call on us to look more carefully on what it actually does, at the social processes that it facilitates, the ways it is strategically employed, and the new systems of power that it produces. The picture that emerges from these analyses is more complex and multidimensional than earlier engagements with the MSM category. But it is also one that is fraught with profound challenges for the future, both for research and for practice. The AIDS epidemic appears to have lost some of its perceived urgency in recent years, but we are still far from the ‘end of AIDS’ promised by the administrators of the epidemic, in a discourse revealed as little more than a smokescreen. We need engaged, critical social research on HIV and AIDS now more than ever.

About the author

Richard Parker is Senior Visiting Professor at the Institute for the Study of Collective Health, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro; Director and President, ABIA – Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association; and Professor Emeritus of Sociomedical Sciences and Anthropology, Columbia University.

References

Aggleton, Peter, and Richard Parker. 2012. ‘Moving beyond Biomedicalization in the HIV Response: Implications for Community Involvement and Community Leadership among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender People’. American Journal of Public Health 105 (8): 1552–58. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302614.

Almeida, Vagner. 1997. Cabaret Prevenção. Rio de Janeiro: ABIA. http://hsh.fw2web.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/LIVRO-Cabaret-Preven%C3%A7%C3%A3o-1997.pdf.

Alonso, Ana Maria, and Maria Teresa Koreck. 1989. ‘Silences: “Hispanics”, AIDS, and Sexual Practices’. Differences 1: 101–124.

Benton, Adia. 2015. HIV Exceptionalism: Development through Disease in Sierra Leone. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Beyrer, Chris, Stefan D. Baral, Frits Van Griensven, Steven M. Goodreau, Suwat Chariyalertsak, Andrea L. Wirtz, and Ron Brookmeyer. 2012. ‘Global Epidemiology of HIV Infection in Men Who Have Sex with Men’. Lancet 380 (9839): 367–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6.

Beyrer, Chris, Varun Gauri, and Denise Vaillancourt. 2005. Evaluation of the World Bank's Assistance in Responding to the AIDS Epidemic: Brazil Case Study. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Boellstorff, Tom. 2011. ‘But Do Not Identify As Gay: A Proleptic Genealogy of the MSM Category’. Cultural Anthropology 26 (2): 287–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2011.01100.x.

Carrier, Joseph M. 1989. ‘Sexual Behavior and Spread of AIDS in Mexico’. Medical Anthropology 10 (2–3): 129–42. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01459740.1989.9965958.

Dionne, Kim Yi. 2017. Doomed Interventions: The Failure of Global Responses to AIDS in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dowsett, Gary. 1989. ‘“You’ll Never Forget the Feeling of Safe Sex!” AIDS Prevention Strategies for Gay and Bisexual Men in Sydney, Australia’. Paper presented at the WHO/GPA Workshop on AIDS Health Promotion Activities Directed towards Gay and Bisexual Men, Geneva, Switzerland, 29–31 May.

Geertz, Clifford. 1974. ‘“From the Native's Point of View”: On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding’. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 28 (1): 26–45. http://hypergeertz.jku.at/GeertzTexts/Natives_Point.htm.

Geertz, Clifford. 1988. ‘I-Witnessing: Malinowski’s Children’. In Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author, 73–101. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gusterson, Hugh. 1997. ‘Studying Up Revisited’. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 20 (1): 114–19. https://doi.org/10.1525/pol.1997.20.1.114.

Kenworthy, Nora, and Richard Parker. 2014. ‘HIV Scale-Up and the Politics of Global Health: Introduction’. Global Public Health 9 (1–2): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.880727.

Kenworthy, Nora, Matthew Thomann, and Richard Parker. 2018. ‘From a Global Crisis to the “End of AIDS”: New Epidemics of Signification’. Global Public Health 13 (8): 960–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1365373.

Killen, Jack, Mark Harrington, and Anthony S. Fauci. 2012. ‘MSM, AIDS Research Activism, and HAART’. Lancet 380 (9839): 314–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60635-7.

King, Edward. 1993. Safety in Numbers: Safer Sex and Gay Men. London: Cassell.

Kohut, Heinz. 1971. The Analysis of the Self. New York: International Universities Press.

Lancaster, Roger N. 1988. ‘Subject Honor and Object Shame: The Construction of Male Homosexuality and Stigma in Nicaragua’. Ethnology 27 (2): 111–25.

McKay, Tara. 2016. ‘From Marginal to Marginalised: The Inclusion of Men Who Have Sex with Men in Global and National AIDS Programmes and Policy’. Global Public Health 11 (7–8): 902–922. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17441692.2016.1143523.

Nader, Laura. 1972. ‘Up the Anthropologist: Perspectives Gained from Studying Up’. In Reinventing Anthropology, edited by Dell Hymes, 284–311. New York: Vintage Books.

Parker, Richard. 1987. ‘Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome in Urban Brazil’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1 (2): 155–75. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1987.1.2.02a00020.

Parker, Richard. 1999. Beneath the Equator: Cultures of Desire, Male Homosexuality, and Emerging Gay Communities in Brazil. New York: Routledge.

Parker, Richard. 2012. ‘Critical Intersections/Engagements: Gender, Sexuality, Health, and Rights in Medical Anthropology’. In Medical Anthropology at the Intersections: Histories, Activisms, and Futures, edited by Marcia C. Inhorn and Emily A. Wentzell, 206–38. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Parker, Richard. Forthcoming. Imagining the Epidemic: The Politics of AIDS and the Invention of Global Health. Rio de Janeiro: ABIA/GAPW.

Parker, Richard, Peter Aggleton, and Amaya G. Perez-Brumer. 2016. ‘The Trouble with “Categories”: Rethinking Men Who Have Sex with Men, Transgender and Their Equivalents in HIV Prevention and Health Promotion’. Global Public Health 11 (7–8): 819–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1185138.

Parker, Richard, Carmen Dora Guimarães, and Claudio J. D. Struchiner. 1989. ‘The Impact of AIDS Health Promotion for Gay and Bisexual Men in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’. Paper presented at the WHO/GPA Workshop on AIDS Health Promotion Activities Directed towards Gay and Bisexual Men, Geneva, Switzerland, 29–31 May.

Parker, Richard, Renato Quemmel, Katia Guimares, Murilo Mota, and Veriano Terto, Jr. 1995. ‘AIDS Prevention and Gay Community Mobilization in Brazil’. Development 2: 49–53.

Parker, Richard, and Veriano Terto, Jr., eds. 1988. Entre Homens: Homossexualidade e AIDS no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: ABIA.

Patton, Cindy. 1990. Inventing AIDS. New York: Routledge.

Patton, Cindy. 1996. Fatal Advice: How Safe-Sex Education Went Wrong. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Prout, Alan. 1992. ‘Illumination, Collaboration, Facilitation, Negotiation – Evaluating the MESMAC Project’. In Does it Work? Perspectives on the Evaluation of HIV/AIDS Health Promotion, Vol. 1, edited by Peter Aggleton, 77–91. London: Health Education Authority.

Prout, Alan, and Katie Deverell. 1995. Working with Diversity: Building Communities: Evaluating the MESMAC Project. London: Health Education Authority.

Rios, Luís Felipe, Vagner Almeida, Richard Parker, Cristina Pimenta, and Veriano Terto Júnior. 2004. Homossexualidade: produção cultural, cidadania e saúde. Rio de Janeiro: ABIA.

Treichler, Paula. A. 1999. How to Have Theory in an Epidemic: Cultural Chronicles of AIDS. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Watney, Simon. 1987. ‘The Spectacle of AIDS’. October 43: 71–86.

Watney, Simon. 1994. Practices of Freedom: Selected Writings on HIV/AIDS. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Wright, Joe. 2013. ‘Only Your Calamity: The Beginnings of Activism by and for People with AIDS’. American Journal of Public Health 103 (10): 1788–98. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301381.

Endnotes

1 Back

The ‘Denver Principles’ refers to a declaration, written in June of 1983, by the advisory committee of the People with AIDS Coalition, at the Fifth Annual Gay and Lesbian Health Conference in Denver, Colorado, in the United States. The Denver Principles are often characterized as the beginning of a focus on self-empowerment and self-determination on the part of people living with HIV and AIDS (see Killen, Harrington, and Fauci 2012; Wright 2013).