Rethinking repetition in dementia through a cartographic ethnography of subjectivity

—

Abstract

Introduction

Over the course of a decade of voluntary work, and a year’s intensive fieldwork in an Orthodox Jewish care home (‘the Home’) in London from 2014 to 2015, [note 1] I observed the somewhat repetitive bodily practices of residents living with dementia. For example, as I detail below, Daniella and Ayla had patterned bodily movements and utterances as they headed to the dining room for breakfast, where they had pre-arranged seats and a designated table partner at a scheduled time and place. To minimise any confusion, distress, or anxiety that could be caused by changing seating arrangements, the Home recommends that, at the beginning of their residency, residents choose their own seats, in consultation with staff and significant others, to reflect their interests and preferences. Since Daniella and Ayla came to the Home in 2011 and 2010 respectively, their bodies had thus repeated, habitualised, and routinised this ‘task’ of sitting down for a meal.

What drew my attention was how, despite this routinisation, their journeys to their seats were heterogeneous and dependant on encounters and interactions with their immediate social, organisational, and material surroundings. Care workers often perceived and described these journeys in a negative way, drawing attention to residents’ repetitive sayings, behaviours, and actions, such as obsessing about a particular seat, pacing, murmuring, asking the same questions, uttering the same statements, knocking, withdrawing, and so forth. Accordingly, they treated Daniella and Ayla’s bodily practices as either just signs of institutional routinisation, or as behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia – referring, for example, to Daniella’s ‘wandering’ and ‘obsession’ and Ayla’s ‘anxiety disorders’ and ‘depression’.

In recent decades, some anthropologists have taken the feeling body as a central theme, as the ‘existential ground of culture and self’ (Csordas 1994). Beyond thinking of it as a mere recipient of or witness to cultural symbols and representation, the feeling body has come to be regarded not only as a ‘source’ of perception, but also as constitutive of social practice and culture through the everyday bodily encounters through which people dwell in the world (De Antoni and Dumouchel 2017, 191). There has been a dramatic increase in studies of people’s subjective experience of living with dementia (including self, subjectivity, and personhood), which together challenge the cultural and biomedical construction of unbecoming and social death (see, for example, Chatterji 1998; Cohen 1998; Hydén and Antelius 2017; Kaufman 2006; Leibing 2006; McLean 2007; Taylor 2008). Nevertheless, as Elizabeth Herskovits (1995) points out, people continue to struggle with the very notion of self and the constitution of subjective experience. Indeed, we still experience a twofold ontological and epistemological crisis in recognising dementia (Herskovits 1995; Hinton and Levkoff 1999; Taylor 2008) and in ways of knowing dementia (Leibing 2006; Lock 2005). People with dementia are often described as ‘the displaced’ in a ‘non-place’ (Reed-Danahay 2001, 48), or as being in a ‘timeless world’ (Edwards 2002, 184, italics in original; see also Gjødsbøl and Svendsen 2019). Furthermore, to date, little scholarship has explored the affective dimension of people’s lived experience of dementia – that is, how those affected perceive, think, attune to, and respond to their worldly surroundings. Even less scholarly attention has been paid to the relationship between the creative, expressive, performative bodily dimension of affect and repetitive phenomena in the dementia context.

Rather than interpreting repetitive actions and utterances as pathological and abnormal, in this article I aim to extend how we approach, perceive, and understand such repetitive phenomena through the use of cartographic ethnography, paying particular attention to the affective dynamics of repetition. To this end, I first address the potential of cartographic ethnography by drawing on the work of Fernand Deligny, in line with Tim Ingold’s notion of dwelling, to better approach repetition as bodily affective practice. After tracing Daniella and Ayla’s journeys to breakfast, I highlight the affective differentiation of repetition that feeling bodies act and enact. Daniella and Ayla, I show, directly engage with their ever-changing lifeworld in terms of glance, facial expression, tone, tempo, and rhythm, in a form of bodily ‘resonance’ and ‘correspondence’ (Ingold 2017, 19). I argue for a move away from predominant biomedical perceptions of repetitive bodily practices and towards understanding them in terms of their affective affordance in the making of subjectivity. This leads to my critical engagement with recent ontological and affective turn/oriented research, specifically that which focuses on ontogenetic multiplicity, relational epistemology, and discursive practice. Finally, I suggest that the subject is a being-in-becoming; that is, that dementia emerges in the process of dynamic, complex, and recurrent interactions, responses, and encounters with its immediate surroundings.

Methods: Mapping feeling bodies

What do Daniella and Ayla’s repetitive practices do? By shifting the intellectual focus from the causes or meanings of these bodily experiences to their values and functions, the affective dynamics of repetition in individual residents invite us to consider an alternative to conventional approaches (e.g., biomedical and therapeutic) and analytical tools (e.g., surveys, observation, and interpretation). This shift demands a new approach that, rather than merely representing the phenomena, can identify the processes of individual events and the relations between repetitive practices and other constitutive components of social life.

Deligny and Ingold offer theoretical as well as practical and ethical insights, which I use to explore how bodily movements, affect, and sensation emerge in the formation of subjectivity – a subjectivity with which, resonating and corresponding, people dwell in the world. This generates a number of questions. First, can an ethnographic mapping change the ways we perceive, look at, and think about repetition, and thus provide a broader understanding of subjectivity in dementia? More specifically, can the lines of movements on the map transcribe the ways in which the subtle, sometimes barely recognisable or otherwise messy and entangled, affective dimensions of repetition are shaped and operate in everyday encounters? How can individual action and response be differentiated and identified from mundane repetition without recourse to established concepts, terms, and thoughts? Finally, how should cartographic ethnographers identify the ordinary affective practices that are entangled not only with felt experience but also with discursive and cognitive experience?

Deligny strongly rejected not only the predominant clinical experiments and institutionalised and therapeutic interventions of his times, but also the pre-existing psychiatric categories, thoughts, and terms. From the 1950s until his death in 1991, Deligny and his colleagues operated ‘residential communes’ in the Cévennes in France, working and living with children and young people living outside of language, namely those with autism (Milton 2016, 285). Deligny’s approach does not categorically differentiate children with autism on the basis of their capacities or abilities to speak, learn, remember, and communicate, nor does it normatively separate the normal and the pathological (Miguel 2015, 137). It also does not see people with autism as mere objects of research, but as both subjects and co-travellers. In doing so, Deligny leads us to ‘draw lines, to initiate an approach not through language’, which his dwellers do not have, but instead ‘through their patterns of movement’ (Logé 2013). Indeed, as he watched these people move around, Deligny drew the lines of their bodily movements on a map, producing what he called ‘wander lines’. His cartographic wander lines do not only offer the foundation of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s rhizomatic thoughts, but also show us the immediate interactions and encounters involving ‘tension and friction’ in everyday life through their torsive, flexible, and vivacious lines of movements (Ingold 2015, 4; see also Deleuze and Guattari 1983). Mapping is thus neither the interpretation nor representation of people with autism, but rather ‘the implicit trace of an activity’ (Ogilvie 2013, 407) – namely, the ‘tracks and traces’ of their slightest bodily movements (Wiame 2016, 44; see also Deleuze 1998). As such, cartographic ethnography allows us to conceptually and empirically explore the bodily affective dimensions of repetition in language, behaviour, gesture, posture, and/or attitude through bodily spatial emergence and expressive performativity. It also allows us to demonstrate bodily repetitive practices not as context-free, biomedically and therapeutically diagnosed, static forms of abnormal episode, but rather as the moving, networking, and expressive performativity of feeling beings – a performativity that, I will show, continues to resonate with the lives of residents, logics of care, and atmosphere through intensive and attentive co-correspondence.

Whilst Deligny’s thoughts and practices provide inspiration for an alternative mapping practice in dementia, Ingold (2007, 2015) is interested in lines of movements from the perspective of a relational ecology of life. He claims that everyone and everything dwelling in the world travels along lines, entangled and enmeshed with one another. More importantly, Ingold questions how we live and experience the world, namely through line-making, advocating ‘direct perception through [bodily] engagement’ (Knusdsen 2016, 187), rather than merely interpreting and translating based on a language-privileged epistemology. Beyond the disembodied mind-body and nature-culture dualisms, Ingold (2000) urges us to situate our life by directly attending to the world which we inhabit. He thus overcomes a problem of translation, what he calls ‘the logic of inversion’ (1993, 225), where the detached observer often ‘decontextualises’ or even ‘re-contextualises’ another’s life, culture, or knowledge from an ethnocentric perspective and then ‘inverts back again’ as a representation of the other (Knusdsen 2016, 188). It is particularly invaluable for the study of dementia that this relational ontogenetic notion of dwelling provides a continuous and open-ended world-making from the subjective perspective, which is ‘the same world viewed from another vantage point within it’ beyond Cartesian dualism (Ingold 1993, 226).

Drawing upon Heidegger’s (1971) concept of dwelling, Ingold’s dwelling perspective embraces a relational understanding of human beings ‘as a singular locus of creative growth within a continually unfolding field of relationships’ (Ingold 2000, 5). Animal life and the natural environment are never predetermined, nor isolated from human life; rather, they emerge in the process of direct engagement. Recognising Jacob von Uexküll’s concept of the Umwelt – ‘the world as constituted within the specific life activity of the animal’ (Ingold 1995, 62) – Ingold claims that every creature has its own way of experiencing its world: while a spider can intersect with the life of a fly through its web, the spider does not know the fly’s world (2011, 79–80). Ingold regards such a quality as ‘affordance’, taking James Gibson’s concept of affordances of the environment; that is, what it ‘offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes for good or ill’ (Gibson 1979, 127). Affordance refers to the characteristics of an environment which are only available to the organism through its concerns, needs, and skills, and which provide valuable options for action. To paraphrase, for a person living with dementia, a cup of tea can be perceived as ‘drinkable’ but a wet floor as ‘less walkable’ – in Deligny’s terms, an ‘ecological competence’ (Sauvagnargues 2016, 164). The affordance of an object is thus not an inborn quality, but the way it is perceived, understood, and appropriated by an observer through direct perception rather than through enculturation (Ingold 2018).

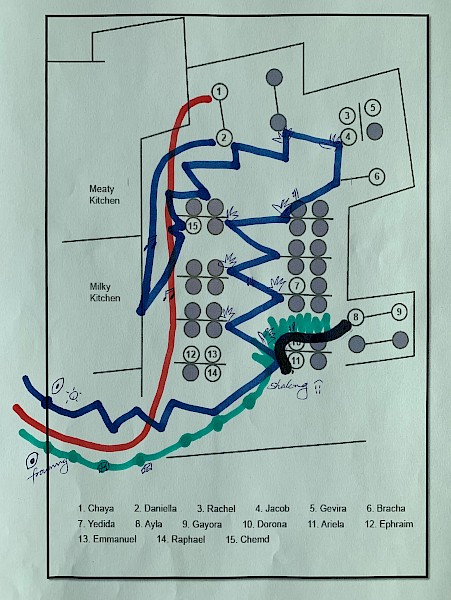

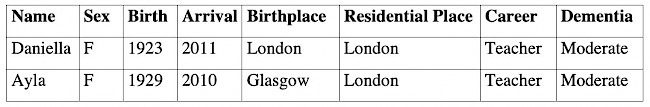

Taking these insights together, I initially drew a basic map of the material landscape showing points of reference (in Deligny’s terms, ‘spotted/markers’) in the everyday life in the Home; for example, the communal area, restaurant, care workers’ desk, sofa, kitchen, lift, window, tables, and so on. On the map, I then drew the trajectories of thirteen individual residents’ journeys to the dining room as they went to have breakfast each day. As time went by, diverse forms, patterns, rhythms, and intensities of lines of movements emerged, and soon my map was covered with lines that curved, zigzagged, juxtaposed, stopped and restarted, went nowhere, and so on. For additional information, I added some words and images alongside the wander lines – which I call ‘wayfaring lines’ –[note 2] including images of eyes, a walking frame, the sun and clouds, and words describing dragging, frowning, shaking, crying, and other affective feelings. Between August and October 2014, I mapped the bodily affective practices of twelve residents living with early to moderate dementia and one resident without dementia. Due to the limited space available here, I focus only on two residents (Daniella and Ayla).

Table 1. Demographic data for key participants.

Glance

Daniella walked in a lively way, with long and light steps, towards the dining room. She was greeted by the morning sun, gentle classical music, and delicate smells of baked bread and fresh fruit coming from the kitchen. Standing at the entrance to the dining room, she gently closed her eyes for a moment. With a contented smile, she looked into the dining room. She suddenly shook her head as if disappointed, and then moved around the room. Usually she would go directly to her designated seat, but this time she walked slowly, zigzagging. She looked over each table and asked the other residents what they were having for breakfast. Yet, no meaningful conversations seemed to take place. Daniella often spoke in a very weak voice, murmuring to herself, so it was unlikely that the other residents could understand what she was saying. She even left the table before the other residents could reply. Some had already been distracted by her presence and her intermittent knocking, and had stopped eating their meals to look at her with a frown. Maria, a staff member in her late forties, asked Daniella not to stand in between the tables and to sit down in her place so that other residents could get past. When Daniella finally arrived at her table, though, she still hesitated before sitting down. This was unusual behaviour for Daniella, who had become well-known for her obsession with her seat, not only among staff but also among other residents: since her arrival at the Home in 2011, she had never given up her chair to another person, despite sometimes insisting that others yield theirs to her. Maria asked Daniella again if there was a problem. Daniella said something, but it sounded as though she was mumbling to herself again. However, it was clear that she had changed her mind and decided not to sit down after all. She moved to the neighbouring table, where Maria was assisting another resident, Hyden, with her meal. Daniella tried to take a seat next to Hyden, but soon stood up again. She got up and down repeatedly, and walked around the table. Hyden was distracted and her meal dripped from the side of her mouth. Maria asked Daniella to sit down in her seat and to stop interrupting Hyden. After a while, Daniella left and walked to the bar in front of the Milky (dairy food) kitchen for breakfast. She picked up a bowl and took some cereal. At this moment Chaya, her table partner, entered the dining room. Daniella smiled brightly and her eyes opened wide, and then greeted Chaya and stood aside for her friend to pass. Chaya went to her seat, put her belongings on it, came back to the bar, and looked over the two types of cereal. Daniella stopped talking and followed Chaya with her cereal, looking cheerful and happy, as though nothing had happened.

Daniella’s customary movements were typically direct and purposeful, often corresponding with Chaya’s. On this occasion, however, Daniella’s lines of movements were much more complicated than usual, emerging in forms of straight, zigzagged, and juxtaposed lines. What drew my attention was her sudden stopping – a slight faltering, though momentary, at the entrance of the dining room. This was quite different from other occasions when she either came with her table partner or else found her already in the dining room. This moment of faltering reminded me of Daniella’s social relations, in that she was almost always with Chaya, who had become a best friend since they had met each other in the Home. This transformative movement of Daniella’s bodily feeling reveals how place, things, and social relations shape affective atmosphere and, at the same time, how Daniella’s feeling body attunes to, resonates with, and is attached to the constantly changing here-and-now situation. In this regard, Ingold (2000) provides an insightful conceptual framework of ‘affective atmospheres’, in line with Gernot Böhme’s (1993) notion of ‘atmosphere’, to understand the relationships between people, things, and atmosphere. Böhme (1993, 122) understands atmosphere as something that should neither be isolated nor seen as ‘free floating’; rather, it ‘is the reality of the perceived as the sphere of its presence and the reality of the perceiver, insofar as in sensing the atmosphere she/he is bodily present in a certain way’. Looked at this way, Daniella’s dramatic transformative glance revealed the immediate and unmediated affective response to the here-and-now, which has hitherto been largely unexplored, kept within the bracket of individuals’ trivial bodily movements or pathological signs or symptoms. Despite being so familiar and ubiquitous as to be ‘the very medium of human transaction’, and the foundation of human perception and knowledge, the ‘glance’, whose forms range from a mere blink to a piercing look, has received little attention in academia (Casey 1999, 80).

As Daniella’s glance across the threshold of the dining room suggests, her relations with others, things, and the environment were distanced by a momentary affective transformation, which was revealed through her frowning and shaking her head. Strikingly, the return journey of the glance is not always travelled or distributed equally. Daniella was initially satisfied with her surroundings: the classical music, the smells of bread and tea, and the warm morning sunshine. But this was quickly transformed into disappointment over the absence of Chaya, reflected in her glance. As Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1964) argues, trees do not see the seer (us) in the same way as the seer sees them; our glance is not merely mechanical or metaphysical, but is always relational, interdependent, and intersubjective, relating not only to people but also to non-human entities and our surroundings. Because of this asymmetrical relation between seeing and being seen, the glance is always open-ended, undetermined, and indefinite, something ‘above and beyond’ the ready-made interpretive look or language-oriented gaze that only flows in a one-directional or lineal way (Logé 2013). In other words, the glance does not indicate a state of glancing, but rather a way of becoming that is characterised as ongoing bodily rhythmic movement and transformation through encounters and relations within a milieu. Consequentially, ‘glance’ is defined not as a noun but as a verb involving a duration of movement, however momentary, and the opening and closing of one’s eyes is characterised as interdependent, contingent, and relational. As such, Daniella’s glance infinitely bifurcates and diffuses in the process of interactions and encounters. Needless to say, every single momentary transformation within the glance becomes ‘a source of the differentiation of duration and the absolute newness of each becoming’ (Casey 1999, 97).

Face

It was 8.45am. Like Daniella, Ayla paused at the entrance to the dining room, glancing at her surroundings. Her glance lasted a little longer than Daniella’s quick look. Due to her deteriorating vision, caused by senile macular degeneration and cataracts, she had to work hard to perceive and sense her here-and-now situation. Ayla often stood still, expressionless. A care worker passed by her, gently taking her hands and greeting her warmly. Ayla quickly traced the origin of the touches and voice and guessed who the care worker was. After exchanging short greetings, Ayla tried to talk about her daughter, but the staff member had already walked a short distance away, telling Ayla that they could talk later, after breakfast. Ayla sighed and then started walking again, extremely slowly, dragging rather than pushing her walking frame. After every step, she stopped for a moment to look at her surroundings. She was often suddenly startled, prompting her to gaze around and linger for a while, looking in the direction from which she had heard something. Although it was only a short distance from the entrance to her seat, Ayla’s way of walking meant that it usually took her a substantial amount of time to get there.

Ayla continued to look around until she recognised me sitting at another resident’s, Dorona’s, table, and she stopped walking. Her pupils dilated and her previously inexpressive face broke into a bright expression, a mixture of surprise and delight. She stretched out her arms and took hold of my hands, saying she had missed me so much, and asking where I had been and what I had been doing over the past few days. I told her that I had been trekking over the weekend with my housemates, and asked her about her weekend. She said, disappointed, that nothing had happened and it had been quite tedious. She did not mention her daughter’s visit the previous Saturday. After she had finished telling me about her weekend, we were quiet for a moment, and I suggested she sit down. However, she did not want to move; instead, she turned towards Dorona’s table and continued to talk. Ayla asked about my family and my studies. She did not wait for me to finish before asking what I would be doing that day, and so on. Then her voice trembled as she started to talk about her daily life at the Home, asking me to take her home to where she used to live with her late husband. I had heard this many times from Ayla. As her story progressed, her face, complexion, and emotions were dramatically transformed. Her voice faltered and I saw that she was about to burst into tears. She asked again whether I could take her out of the Home. Holding her faltering hands and looking at her tearful face, I listened to her for a while. The sensory assemblage of classical music, morning sunshine and food, and the presence of other residents was suddenly diminished in the shadow of the affective scenes. Ayla did not move, blocking the other residents and staff, and continued to tell me about her insecure and anxious situation. Although Dorona looked uncomfortable, Ayla does not seem to be paying her any attention. Dorona stopped drinking her tea to look up at us, but did not join in the conversation, nor did she complain about Ayla; after a while, she just looked out of the window. I told Ayla that I was in the middle of a meal with Dorona, and asked her if she would like to move back to her own chair. Taking a step aside, Ayla looked around the table for an empty seat. She tried to sit on the other side of Dorona, where she had never sat before, but I expected that Frederik (who normally sat there) would soon come to move her, so I told her that she should sit in her designated seat by the window. I guided her there, telling her that I would be back after finishing my breakfast with Dorona. Ayla was not able to sit and wait to be served by staff; she did not even look at the menu. She got up and sat down repeatedly with a slightly annoyed expression on her face, as if she felt that there was nothing of interest to her there. She turned again towards Dorona’s table, looking at us with a miserable face, as if she was yearning for me to come as soon as possible. Her helpless and hopeless facial expressions reflected how she felt.

Once Dorona had finished her breakfast, I moved over to Ayla. She grabbed my hands again and looked at me with a desperate face. Gayora, her table partner, and Yedida, her friend at a neighbouring table, had not arrived yet. I took a chair from the next table and sat on her right-hand side, leaving Gayora’s seat free. I asked her what she wanted to eat. She waved at the menu and said that nothing was suitable for her because everything was dull and dry. For her, the meals in the Home were not good enough to eat. Instead of breakfast, she proposed going out for a cup of tea and cake in the garden café. Her voice still faltered slightly. The café was not open yet so I suggested that she have a light meal now and we could go for a walk another day. I explained that I was very tired because I had been busy overnight. She listened to my story and started to eat. Her brow became less furrowed and the deep wrinkles around her eyes smoothed out and straightened. Her face became calm, and her immediate disposition was gradually transformed as she settled and became peaceful.

As Ayla’s gestures, postures, attitudes, utterances, and bodily movements in relation to Dorona (and myself, the other residents, and staff) showed, her encounters with others were not uniform. In particular, her facial expressions did not always reflect the same intensity of feeling, nor did they merely represent or mirror her static inner voices. The signifiers do not always match with the signifieds; there are always slippages, excessiveness. Unlike Charles Darwin’s generalised and categorised facial expressions in The Expression of the Emotions ([1872] 1965), Ayla’s face was constantly transforming in the process of interacting and encountering with the faces of others. As Silvan Tomkins (1995, 89) argues, the face is of ‘the greatest importance in producing the feel of affect’. Indeed, Ayla’s expressive facial feelings not only appeared in the process of resonating and corresponding with her immediate milieu, involving ‘the facial muscles, the viscera, the respiratory system, the skeleton, changes in blood flow, vocalisations, and so on’ (Thrift 2004, 75). They were also in the process of assembling her past enmeshed affective bodily experiences with staff members, residents, and the researcher, and her consequential expectation, hope, or imagination.

Likewise, how Ayla approached and perceived a face was quite different from the Levinasian face. According to Emmanuel Levinas (2012), the face of the Other is characterised as vulnerable, naked, and defenceless; the impossibility of reducing the Other to sameness brings persons to a particular relation that demands an ethical obligation of caring for the Other. [note 3] Such a primary and primordial sense of responsibility towards the Other is only established through pre-epistemological and pre-ontological face-to-face encounters (Levinas 1989). In contrast to Levinasian ethical, pre-reflective encounters with the face, Ayla sensed the face through its enactment of communication, socialisation, and individualisation. It neither merely reflected her thoughts and feelings at a time, nor was it fixed, but was made up of potential, existing in the form of the virtual (Deleuze 1986, 99). It was also non-identical, implying that a face is much more transformative, complicated, and multidimensional than Levinas argues, emerging in the process of ongoing interaction, communication, and encounters (Deleuze 2004). Accordingly, in order to explore the ways in which Ayla perceived and related to the faces of others, we need to ask not what a face is or what a face can represent, but what a face can do (Rushton 2002). To take this a step further: Ayla’s face showed a varied mode of repetitive expressive performance in the process of immediate engagement. This repetition then invites reflective and intensive methods of response and resonance. Paradoxically, because of this unknowability and unfamiliarity with the reflective and thoughtful faces of people around her, the faces of others in turn call for an eternal return to figure out this mystery. In contrast to the reflective face, the intensive face is characterised as transformative, transitory, and dynamic. Ayla moved and felt at the same time, resonating with the faces of others and her surroundings with diverse and ever-changing facial expressions and voices that differed in tone, speed, and volume. The affective and sensory dimensions of Ayla’s repetitive bodily actions, enactments, and utterances, exposed through bodily performativity, are embedded in her bodily affective practices.

As such, Ayla’s feeling body and her feelings are closely connected, ‘resonating together, interfering with each other, mutually intensifying, all in unquantifiable ways apt to unfold again in action, often unpredictably’ (Massumi 2002, 1). In particular, I take her anxiety, hopelessness, and helplessness as evidence of her existential crisis, which is described as lines of bodily movements (however slight), gestures, postures, and utterances on the map. These wayfaring lines illustrate Ayla’s feelings of insecurity and unfamiliarity with the dining room, even though she repeats this routine daily. In Heidegger’s sense ([1953] 2010, 328), she feels her own existential experience of ‘not-being-at-home’, but this does not mean that her ontological being is nullified or has become an ‘inauthentic being’. Instead, she responds to and resonates with the world in the most dramatic and singular way, on her own terms and within her capacity. In other words, Ayla’s anxiety is embedded in the individual parts of her organs, sinews, and muscles, while her organic body simultaneously reflects such feelings, affects, and emotions by transforming, relating, adding, relieving, and exposing. These individual becomings of bodily expressive performativity on her face reveal a kind of momentary transformation, constructing her ever-changing subjectivity in repetition, and concomitantly providing a platform for us to witness the formation of her subjectivity.

Tone, tempo, and rhythm

While wayfaring lines help us to consider how affective experiences emerge by tracing how Daniella and Ayla’s feeling bodies sensed and perceived the world surrounding them, these lines also lead us to rethink a range of affective tones, tempos, and rhythms, which are revealed through lines of expressive performativity. As feeling bodies move, their wayfaring lines become entangled with the lines of others, with things and the material environments unfolding the affective ‘meshwork’ of social, material, and temporal lines (Ingold 2011, 63). Daniella’s walking becomes entangled with different tempos, speeds, durations, and rhythms. For example, her behaviour and attitude when she saw Chaya were different from how she was around Hyden. Her ways of walking before and after encountering Chaya differed in terms of the intensity of her step: when Chaya appeared, she no longer hesitated, nor was she slow-footed, instead stepping lightly and quickly. Likewise, depending on whom Daniella was talking to, the length, tonality, and volume of her utterances are different. When she is familiar with residents, she stays longer, conversing in a friendly way with them. Otherwise, her voice is weak and she mumbles, as it was in the example described above. Notably, when Daniella reached a table where three male residents were sitting, she did not even knock on the table, nor did she ask them anything; instead, she just passed by onto the next table. Although she hesitated for a while when Maria asked her not to interrupt the other residents’ breakfast, she continued to knock and to ask questions.

Meanwhile, Ayla’s wayfaring lines move extremely slowly, but this does not mean that she stops moving; her sense and sensibility are rather widely exposed to her surroundings. She is easily frightened and reacts quickly to external sensory, haptic, and motor stimulations, such as the sound of kitchen utensils falling, hearing her name, or a touch on her body. As such, her lines of affect appear to become more sensitive, hypervigilant, and vulnerable, although her bodily resonances towards such exterior-sensorial stimulations dramatically fade away once she recognises who/what they are and where they come from. Likewise, in the example above, once Ayla recognised my face, her shaking and restless wayfaring line was no longer divergent or swaying; instead, she tried to bring herself closer to my lines of movement and almost synchronised with me, expressing her fluctuating and multifarious affective feelings through her bodily performativity. Since Ayla moved into the House in 2010, we had established a very close relationship. She often asked care workers about me when she had not seen me for a while. Although she hardly ever remembered my name, all the care workers working in the unit recognised who she referred to as ‘the care boy’. As such, her different intensities of embodied and kinaesthetic affinity revealed her heterogeneous expressivity of affective perceptions towards other people and things around her.

Indeed, Ayla repetitively told me that there was hardly anything and anyone that she was fond of in the here-and-now moment. Unlike in the home she had shared with her late husband, there were no oak trees in the garden at the Home; no rooms like the ones she used to play Bridge, knit, and read in with her best friends; no memories of her families and pet dogs; and none of the beautiful furniture that she used to polish every day. Her vision had deteriorated dramatically, meaning she could no longer knit, which had been one of her favourite things to do; this also put an end to my personal knitting lessons, one of her happiest hours. After falling several times, Ayla had had a hip operation in 2014, and accordingly she could no longer walk or run like she used to. Although she disagreed and was unwilling, she was strongly urged to use a walking frame, which she described as ‘disgusting’ and ‘ugly’. She had also lost two teeth, and her beauty accessories, such as rings, earrings, and underwear, kept being ‘stolen’.

Quickly, Ayla’s facial complexion gained colour and soon turned to yellow, pale, and then red. Her hands faltered and her eyes became watery and red. Her pulse was suddenly beating fast. Her past experiences and memory made her body resonate, rising and falling ‘not only along various rhythms and modalities of encounter but also through the troughs and sieves of [her] sensation and sensibility’ (Seigworth and Gregg 2009, 2). Simultaneously, her expressive bodily performativity echoed my response. When she started talking, she poured out what she wanted to say and spoke almost without stopping. And then once there was a lull in the conversation, her voice became weak and thin, and she spoke as if there were tears in her eyes. Her expression quickly transformed into one of misery.

If the purpose of communication is to connect or mediate with others – to establish a certain relation or network by using verbal or nonverbal language – then repetitive actions, doings, and utterances are a form of communication. For example, Daniella’s speech was performed in the form of a soliloquy, yet her affect was expressed outwardly. Here, the terms of language must be applied carefully. Her movements, gestures, sensations, and mumblings did not imply that she wanted to communicate anything directly; rather, her communication emerged in the process of repetition, as a mode of (dis)connection and of (non-)being. As Henri Lefebvre (2004, 6–7) suggests, every rhythmic repetition inherently involves differentiation in the process of engagement with the surroundings as life enfolds – what Ingold calls ‘differences within repetition’ (2011, 60). A corollary of this is that Daniella’s steps and murmurings echo not only her changed situation, but also her attentive attunement, by way of differentiating her steps. In other words, her wayfaring implied an empty feeling due to the absence of Chaya, and the minute differences in intensities of wayfaring lines addressed her affinity to and belongings towards her surroundings based on her fragmented memory and here-and-now affectivity. In this context, I agree with Ingold’s extension of André Leroi-Gourhan’s (1993, 309–310) notion of ‘rhythmic quality’ to ‘rhythmic repetition’. Ingold (1999, 437, 2011, 60) claims that repetition is not mechanical and automatic but rather that each movement is ‘felt’ and recognised through the body in the process of continuous bodily ‘attunement’ to ever-changing circumstances. Therefore, affect concerns not only attending, attuning, and responding to the world, but also weighing the relative significance, intention, or tendency of events, things, people, and situations. In other words, an affective quality is neither neutral nor a mere representation of the reality, but emerges as a way of experiencing, perceiving, and expressing. It is part of the process of engaging and encountering through which people dwell in the world. This complexity suggests a need to revitalise the relational qualities of repetitive practices in dementia by shifting away from the individual intrinsic value and singularity underpinned person-centredness (Kitwood 1997) to relatedness with one another dwelling in the world. The relational understanding of affect should be foregrounded in perceiving intercorporeal and intersubjective social fabric (Blackman 2012; Blackman and Couze 2010). In other words, the bodily repetitive practices of these two residents are already and always situated dementia-in-the-world, not as a pre-existing individual entity, but as a process that emerges ‘through entangled processes of relating’ (Juvonen and Kolehmainen 2018, 4) and which is characterised as contingent, distributive, and heterogeneous.

Relational understanding of affective and discursive practices

Daniella and Ayla’s repetitive practices are neither coherent nor stable; they are instead often fragmented, dissonant, and fluctuating. It would be impossible to understand why, for example, Daniella’s and Ayla’s wayfaring lines changed so dramatically within a very short period of time if I traced single lines of movement alone, without comparing them with other lines and their own past traces of encounters and relations. However, Daniella and Ayla’s relations and encounters seem to be neither open-ended or transparent, nor all-inclusive or neutral; their lines of movements show kinds of movements such as (un)cutting, twisting, diverting, overlapping, corresponding, knotting, and so on. Unlike a Deleuzian conceptualisation of affect as rhizomatic and open-ended movement, in reality the possibility of these two residents’ social fabric and their ways of weaving the network are limited by the specific social, biographical, organisational, and environmental circumstances. Their affective performativities are not evenly or uniformly shared, but are heterogeneously and contingently distributed across people, things, and surroundings at a particular time. Thus, the fabric of social relationships correspondingly affects and is affected by this distributed complexity.

Deligny distinguished between people with autism and subjects in a theoretical way and found it necessary to ‘juxtapose’ his co-travellers with subjects (Milton 2016, 286). Strictly speaking, the mapping forced him to see an autistic mode as an ‘a-subjective, a-reflexive presence that nevertheless does belong to our world to the extent that this a-subjectivity is also a part of ourselves as subjects, the part that is linked to space and place’ (Ogilvie 2013, 409). It is through this that Deligny attempted to reveal the ontological logic of people with autism as ‘acting’ outside of notions of self, ‘inhabiting a pre-lingual network’ in contrast to that of the ‘humans-that-we-are’: that is, ‘a kind of idealised functional state of normative humanity’ living in ‘the symbolic world of language’ (Milton 2016, 286; see also Deligny 2013, 2015). Deligny did not see autism as pathological, but as a different way of sensing, acting, moving, being, and dwelling in the same world. Contrary to speaking subjects, Deligny would call the children ‘mute’ rather than ‘autistic’ and rarely used the terms ‘subject’ or ‘subjectivity’ in relation to people with autism (Ogilvie 2013, 409).

Here, Deligny’s cartographic, residential experiments and Ingold’s dwelling perspective together provide invaluable insights about how to know the other, not only in and of itself, but also in relation with one another. They also suggest ways for dwelling well with others living in the same world, calling for a relational understanding and embracing the modern distinction between the way of knowing and the way of being. In particular, their ways of addressing events, encounters, and interactions through bodily performativity (Deligny) and direct engagement (Ingold) offer inclusive, generative, ethical, and empowering ways of approaching and understanding beyond mental and physical capacity and ability. As Jeannette Pols (2005, 216) points out, even people in the advanced stages of dementia ‘enact’ situated and relational ‘appreciations’ through expressive performativity in the process of immediate engagements, and this calls for a shift from ‘the patient perspective’ to ‘the subject/patient position’. In this sense, it is reasonable for Ingold to differentiate his ‘ontogenetic multiplicity’ from Philippe Descola’s (2013) ‘ontological pluralism’. Ingold criticises the latter as a ‘museum of ontology’, in that:

the one world we inhabit is not a world that is primordially the same for all, yet which offers a limited set of solutions for its comprehension, but a world of perpetual and potentially limitless differentiation, in which ‘coming to terms’ is a lifelong task that is carried on, just as life is, in the very conduct and unfolding of our relations with others. (Ingold 2016, 302–303)

In other words, Daniella and Ayla’s affective practices are characterised as an evaluative or appraisal capacity of meaning-making through which people, things, and the environment appear to them as ‘friendly’, ‘worthwhile’, ‘indifferent’, and so on; namely, ‘affective affordance’ (Gibson 1979). For example, despite Ayla’s imagination, hope, and desire that she could go back to her home in North London, she remains ‘stuck’ in a ‘hospital’, as she describes it. However, her discordance and dramatic transformation of affective quality must be read as her singular way of resonance and correspondence as lived experience, or what Marilyn Strathern suggests as ‘cutting the network’ (1996) through ‘partial connections’ (1991).

The dramatic fluctuations of Daniella and Ayla’s wayfaring lines show a need to rethink repetitive practices in terms of affective intensity. As described above, the forms of the two residents’ bodily resonances are quite different. They depend not only on relations and encounters given their situated time and space, but also on the affective qualities of these relations and encounters, which are closely involved with here-and-now embodied memory, cognition, belonging, imagination, and expectation. Daniella and Ayla perceive time differently in the same place, and they have often even experienced time confusion or an absence of time perception, moving around the Home at midnight or early in the morning. It is the here-and-now moment that I focus on: the momentary transformation of lines of movements in dialogue with Henri Bergson’s (1919) and Deleuze’s (1988) understandings of time and becoming – more precisely, how the residents perceive and experience the flow of time. From Daniella and Ayla’s perspective, temporality is experienced ‘not as linear but as dynamic and heterogeneous’: time does not flow only ‘from past to present to future’, but is ‘multiple and assembling’ (Coleman 2008, 86). The trajectories of these two residents’ affective practices tell us that the ways the residents synthesise time are neither neatly arranged nor transcendental. Here, two residents’ different forms of bodily practices raise a reasonable doubt about how affective feelings charge bodily resonance in response to their compromised memory, cognition, language, and expectation. These are not only manifested through their pre-reflexive bodily movements, but are also reflected and expressed through their ordinary, habitual, and routinised bodily engagements and encounters.

In this respect, it seems too narrow an approach to regard these affective qualities only as ‘pre-cognitive, pre-symbolic, pre-linguistic and pre-personal lived intensities’ (De Antoni and Dumouchel 2017, 92; Massumi 2002), or as ‘a substrate of potential bodily responses, often automatic responses, in excess of consciousness’ (Clough and Halley 2007, 2). As Pia Kontos (2004, 2005, 2006) argues concerning ‘embodied selfhood’ and ‘embodied memory’ – building on Merleau-Ponty’s ([1962] 2002) work on embodiment and Pierre Bourdieu’s (2013) work on habitus – Daniella and Ayla’s bodily movements express not only ‘primordial’ but also ‘socio-cultural ways of being-in-the-world’, performing their entangled and complex social and material relationality between ‘body-self and body-world’ (Kontos, Miller, and Kontos 2017, 184). Weaving the two residents’ repetitive practices offers a much deeper understanding of not only primordial and unconscious aspects of affect, but also discursive meaning-making through ‘affective practices’ (Wetherell 2012). Unlike other affective-turn advocators inspired by the works of Spinoza, Bergson, Deleuze, Guattari, and Massumi, Margaret Wetherell (2012, 19) brings together felt experience and discursive practice, suggesting affective practice as ‘a figuration where body possibilities and routines become recruited or entangled together with meaning-making and with other social and material figurations. […] [An] organic complex in which all the parts relationally constitute each other’. By taking into consideration such discursive practice, her concept of affective practices allows an understanding of how feelings, discourse, memory, cognition, and thoughts are interwoven in everyday life in dementia. In other words, as dementia fluctuates and evolves, embodied affectivity correspondingly emerges, relying more on pre-reflexive and less on discursive practices.

Conclusion: Affective affordance in the making of subjectivity

Drawing on Deligny’s cartographic method, I have attempted to extend his thoughts and practices not only beyond disciplinary boundaries, but also beyond an individualised and medicalised gaze. His legacy offers an understanding of the ontological primordial commonalities of mobile and networked beings outside of language and symbols. It also provides informative epistemological and methodological insights for studying the affective dynamics of repetitive practices in dementia. I now suggest expanding our understanding of the singularity of emerging subjectivity as dementia-becoming in repetition, and I build a potential affective space for dwelling focused on movements, sensations, and affects. These lines of affective performativity are themselves the manifestation of individual residents’ singular ways of subjects-becoming: in sometimes (un)comfortable and (un)familiar circumstances, residents repetitively attempt to (re)make relations with (or distance themselves from) the lives of others, things, and their surroundings. In this process, subjectivity is expressed and exposed in a range of different modalities, such as moving around, glancing, rhythmic movement, and facial expression, and with different intensities of feeling, affect, and emotion in response to the ever-changing lifeworld.

The daily breakfast schedule consists of the same routine over and over again. Care practice becomes standardised and routinised through repetition, and eventually such repetitive bodily experiences are normalised, as residents are rarely asked about their bodily feelings and conditions except as part of medically and therapeutically guided care (Goffman 1961). But are Daniella and Ayla both on the same journey with these repetitive itineraries? Evidently, they are not. When Daniella and Ayla encounter the details of light, smell, people, atmosphere, tables, and weather, they, as wayfarers, continuously resonate with their surroundings in astonishingly varied ways over time. As such, their repetitive practices can be characterised as bodily affective affordance, and repetition should be reconsidered as generative, relational, and situational in the world. Needless to say, repetition here does not mean the exact same actions as before, nor does it refer to something completely different with no relation to past experience and memory. Rather, past events and memories exist in the present ‘virtually’, though often fragmented, so people continue to selectively resonate (through their ways of calling, retrieving, or forgetting) with them as potentially ‘real’ (Deleuze 1988). The future is pulled into the ‘actual present’ in the form of ‘passive expectation’ through ‘contraction’ and ‘synthesis’ (Deleuze 2004, 94–96). In this regard, the repetitive lines of movements are the entangled meshwork of those affected, where their relations and lives comprise a mode of dwelling ‘in an open world’ (Ingold 2008, 1809) that has ‘neither beginning nor end’, such that ‘a line of becoming is always in the middle’ (Ingold 2011, 83).

Likewise, cartographic ethnography should not be regarded as a finished work, because the lines of movements of these two residents will continuously accumulate or disappear as they constantly respond to and resonate with their surroundings. The subject is an entanglement of the new creation of singularity generated by the logic of difference and repetition (Deleuze 2004). It is no surprise that the act of drawing concretises ‘a theatre of subjectivity’ from Deligny, Deleuze, and Guattari’s point of view (Wiame 2016, 38); it thus emphasises the expressive and performative aspects of subjectivity, as well as the process of its formation, which is characterised in this article as affective affordance – that is, ‘dementia-becoming’.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to Andrew Irving, Anthony Simpson, Penny Harvey, and Christopher Davis for their invaluable comments and for supporting this publication. My heartfelt thanks also go to those living with dementia and other significant others in the Home who anonymously contributed to my PhD project. Earlier drafts of this article were presented at the Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth’s 2018 and 2019 conferences in the UK, and the Visual Research Network 2nd Conference in the UK. I would like to thank the panellists who provided helpful ideas. I owe great thanks to the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable and insightful comments on an earlier version of this article, and I also deeply appreciate the support of the Sutasoma Trust through the RAI Radcliffe-Brown Trust Fund/Sutasoma Award (2017).

About the author

Jong-min Jeong holds a PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Manchester. The focus of his recent research has been on the dynamics of affective practices of people living with dementia, paying particular attention to affective dimensions of ordinary ethics, creative affordance, place-making, couplehood, and time in care home settings.

References

Alvarez de Toledo, Sandra, ed. 2013. Cartes et lignes d'erre/Maps and Wander Lines: Traces du réseau de Fernand Deligny, 1969-1979. Paris: Arachnéen.

Bergson, Henri. 1919. Matter and Memory. New York: Dover Publications.

Blackman, Lisa. 2012. Immaterial Bodies: Affect, Embodiment, Mediation. London: SAGE Publications.

Blackman, Lisa, and Venn Couze. 2010. ‘Affect’. Body & Society 16 (1): 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X09354769.

Böhme, Gernot. 1993. ‘Atmosphere as the Fundamental Concept of a New Aesthetics’. Thesis Eleven 36 (1): 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/072551369303600107.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2013. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Oxon: Routledge.

Casey, Edward S. 1999. ‘The Time of the Glance: Toward Becoming Otherwise’. In Becomings: Explorations in Time, Memory, and Futures, edited by Elizabeth A. Grosz, 79–97. London: Cornell University Press.

Chatterji, Roma. 1998. ‘An Ethnography of Dementia’. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 22 (3): 355–382. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005442300388.

Clough, Patricia Ticineto, and Jean Halley. 2007. The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social. Durham: Duke University Press.

Cohen, Lawrence. 1998. No Aging in India: Alzheimer's, the Bad Family, and Other Modern Things. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Coleman, Rebecca. 2008. ‘“Things That Stay”: Feminist Theory, Duration and the Future’. Time & Society 17 (1): 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X07086303.

Csordas, Thomas J. 1994. Embodiment and Experience: The Existential Ground of Culture and Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Darwin, Charles. [1872] 1965. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

De Antoni, Andrea, and Paul Dumouchel. 2017. ‘The Practices of Feeling with the World: Towards an Anthropology of Affect, the Senses and Materiality’. Japanese Review of Cultural Anthropology 18 (1): 91–98.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1986. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. London: Athlone Press.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1988. Bergsonism, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. Massachusetts: Zone Books.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1998. ‘What Children Say’. In Essays Critical and Clinical, translated by Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco, 61–67. London: Verso.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2004. Difference and Repetition, translated by Paul Patton. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1983. On the Line, translated by John Johnston. New York: Semiotext(e).

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 2004. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi. London: Continuum.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Claire Parnet. 2007. Dialogues II, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. New York: Colombia University Press

Deligny, Fernand. 2015. The Arachnean and Other Texts, translated by Drew Burk and Catherine Porter. Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing.

Descola, Philippe. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture, translated by Janet Lloyd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Edwards, Allen Jack. 2002. A Psychology of Orientation: Time Awareness Across Life Stages and in Dementia. Westport: Praeger.

Gibson, James J. 1979. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Gjødsbøl, Iben M., and Mette N. Svendsen. 2019. ‘Time and Personhood across Early and Late-Stage Dementia’. Medical Anthropology 38 (1): 44–58. http://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2018.1465420.

Goffman, Erving. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Chicago: Aldine.

Heidegger, Martin. 1971. Poetry, Language, Thought, translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper & Row.

Heidegger, Martin. [1953] 2010. Being and Time, translated by Joan Stambaugh and Dennis J. Schmidt. New York: State University of New York Press.

Herskovits, Elizabeth. 1995. ‘Struggling over Subjectivity: Debates about the “Self” and Alzheimer's Disease’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 9 (2): 146–164. http://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1995.9.2.02a00030.

Hinton, W. Ladson, and Sue Ellen Levkoff. 1999. ‘Constructing Alzheimer's: Narratives of Lost Identities, Confusion and Loneliness in Old Age’. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 23: 453–475. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005516002792.

Hydén, Lars-Christer, and Eleonor Antelius. 2017. Living With Dementia: Relations, Responses and Agency in Everyday Life. London: Macmillan Education UK.

Ingold, Tim. 1993. 'The Art of Translation in a Continuous World’. In Beyond Boundaries: Understanding, Translation and Anthropolgoical Discourse, edited by Gisli Palsson, 210–230. Oxford: Berg Pulbishers.

Ingold, Tim. 1995. ‘Building, Dwelling, Living: How Animals and People Make Themselves at Home in the World’. In Shifting Contexts: Transformations in Anthropological Knowledge, edited by Marilyn Strathern, 57–80. London: Routledge.

Ingold, Tim. 1999. ‘“Tools for the Hand, Language for the Face”: An Appreciation of Leroi-Gourhan's Gesture and Speech’. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 30 (4): 411–453. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1369-8486(99)00022-9.

Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge.

Ingold, Tim. 2007. Lines: A Brief History. London: Taylor & Francis.

Ingold, Tim. 2008. ‘Bindings against Boundaries: Entanglements of Life in an Open World’. Environment and Planning A 40 (8): 1796–1810. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40156.

Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Taylor & Francis.

Ingold, Tim. 2015. The Life of Lines. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Ingold, Tim. 2016. ‘A Naturalist Abroad in the Museum of Ontology: Philippe Descola's Beyond Nature and Culture’. Anthropological Forum 26 (3): 301–320. http://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2015.1136591.

Ingold, Tim. 2017. ‘On Human Correspondence’. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23 (1): 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12541.

Ingold, Tim. 2018. ‘Back to the Future with the Theory of Affordances’. 8 (1–2): 39–44. http://doi.org/10.1086/698358.

Juvonen, Tulula, and Marjo Kolehmainen. 2018. Affective Inequalities in Intimate Relationships. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Kaufman, Sharon R. 2006. ‘Dementia-Near-Death and “Life Itself”’. In Thinking About Dementia, edited by Annette Leibing and Lawrence Cohen, 23–42. London: Rutgers University Press.

Kitwood, Tom. 1997. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Knusdsen, Are John. 2016. ‘Beyond Cultural Relativism? Tim Ingold's “Ontology of Dwelling” Revisited’. In Critical Anthropological Engagements in Human Alterity and Difference,edited by Edvard Hviding and Synnøve Bendixsen, 181–202. Bergen: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kontos, Pia C. 2004. ‘Ethnographic Reflections on Selfhood, Embodiment and Alzheimer's Disease’. Ageing and Society 24 (6): 829–849. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X04002375.

Kontos, Pia C. 2005. ‘Embodied Selfhood in Alzheimer's Disease: Rethinking Person-centred Care’. Dementia 4 (4): 553–570. http://doi.org/10.1177/1471301205058311.

Kontos, Pia C. 2006. ‘Embodied Selfhood: An Ethnographic Exploration of Alzheimer's Disease’. In Thinking About Dementia: Culture, Loss and the Anthropology of Senility, edited by Annette Leibing and Lawrence Cohen, 195–217. London: Rutgers University Press.

Kontos, Pia, Karen-Lee Miller, and Alexis P. Kontos. 2017. ‘Relational Citizenship: Supporting Embodied Selfhood and Relationality in Dementia Care’. Sociology of Health & Illness 39 (2): 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12453.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2004. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Leibing, Annette. 2006. ‘Divided Gazes: Alzheimer's Disease, the Person within and Death in Life’. In Thinking about Dementia: Culture, Loss, and the Anthropology of Senility, edited by Annette Leibing and Lawrence Cohen, 240–268. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Leroi-Gourhan, André. 1993. Gesture and Speech, translated by Anna Bostock Berger. London: MIT Press.

Levinas, Emmanuel. 1989. ‘Ethics as First Philosophy’. In The Levinas Reader, edited by Sean Hand, 75–87. London: Athlone Press

Levinas, Emmanuel. 2012. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, translated by Alphonso Lingis. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Lock, Margaret. 2005. ‘Alzheimer's Disease: A Tangled Concept’. In Complexities: Beyond Nature and Nurture, edited by Susan McKinnon and Sydel Silverman, 196–222. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Logé, Guillaume. 2013. ‘The Surexpression of Wander Lines’. Mobile Lives Forum. https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/2018/07/16/surexpression-wander-lines-12619.

Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. London: Duke University Press.

McLean, Athena. 2007. The Person in Dementia: A Study of Nursing Home Care in the US. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1964. ‘Eye and Mind’. In The Primacy of Perception: And Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History, and Politics, translated by Carleton Dallery, edited by James M. Edie, 159–192. Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. [1962] 2002. Phenomenology of Perception, translated by Colin Smith. London: Routledge.

Miguel, Marlon. 2015. ‘Towards a New Thinking on Humanism in Fernand Deligny's Network’. In Structures of Feeling: Affectivity and the Study of Culture, edited by Devika Sharma and Frederik Tygstrup, 187–198. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Milton, Damian. 2016. ‘Tracing the Influence of Fernand Deligny on Autism Studies’. Disability & Society 31 (2): 285–289. http://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1161975.

Ogilvie, Bertrand. 2013. ‘Postface/Afterword’. In Cartes et lignes d'erre/Maps and Wander Lines: Traces du réseau de Fernand Deligny, 1969-1979, edited by Sandrea Alvarez de Toledo, 397–413. Paris: Arachnéen.

Pols, Jeannette. 2005. ‘Enacting Appreciations: Beyond the Patient Perspective’. Health Care Analysis 13 (3): 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-005-6448-6.

Reed-Danahay, Deborah. 2001. ‘“This Is Your Home Now!”: Conceptualizing Location and Dislocation in a Dementia Unit’. Qualitative Research 1 (1): 47–63. http://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100103.

Rushton, Richard J. F. 2002. ‘What Can a Face Do? On Deleuze and Faces’. Cultural Critique 51 (Spring): 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1353/cul.2002.0021.

Sauvagnargues, Anne. 2016. Artmachines: Deleuze, Guattari, Simondon, translated by Suzanne Verderber and Eugene W. Holland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Seigworth, Gregory J., and Melissa Gregg. 2009. ‘An Inventory of Shimmers’. In The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg, Gregory J. Seigworth, Sara Ahmed, Brian Massumi, Elspeth Probyn, and Lauren Berlant, 1–26. London: Duke University Press.

Strathern, Marilyn. 1991. Partial Connections. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Strathern, Marilyn. 1996. ‘Cutting the Network’. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 2 (3): 517–535. http://doi.org/10.2307/3034901.

Taylor, Janelle S. 2008. ‘On Recognition, Caring, and Dementia’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 22 (4): 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1387.2008.00036.x.

Thrift, Nigel. 2004. ‘Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect’. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86 (1): 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00154.x.

Tomkins, Silvan S. 1995. Exploring Affect: The Selected Writings of Silvan S. Tomkins, edited by Cses Demos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wetherell, Margaret. 2012. Affect and Emotion: A New Social Science Understanding. London: SAGE Publications.

Wiame, Aline. 2016. ‘Reading Deleuze and Guattari through Deligny’s Theatres of Subjectivity: Mapping, Thinking, Performing’. Subjectivity 9 (1): 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2015.18.

Endnotes

1 Back

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from an NHS research ethics committee. All identifiable data are anonymised.

2 Back

Deligny’s French term lignes d’erre is variously translated as ‘lines of drift’ by Brian Massumi in A Thousand Plateaus (Deleuze and Guattari 2004), ‘lines of wandering’ by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam in Dialogues II (Deleuze and Parnet 2007), and ‘wander lines’ by Sandra Alvarez de Toledo in Cartes et lignes d'erre/ Maps and Wander Lines: Traces du réseau de Fernand Deligny, 1969-1979 (Alvarez de Toledo 2013). In this article, I use ‘wayfaring lines’ to capture the tendencies and orientations of lines that are neither predetermined nor preconditioned; instead, they are open-ended, situational, contingent, and heterogeneous. More importantly, at this time, the term ‘wandering’ – meaning an aimless moving and walking in general – is avoided within the dementia context because of its unhelpfulness in understanding the nature and characteristics of this repetitive behaviour; instead, the terms ‘walking/moving around’ are favoured since they imply purposeful and intentional action.

3 Back

The ‘Other’ is a translation of the French autrui which signifies ‘the other person’ or ‘someone else’. Levinas usually uses it in the singular to emphasise face-to-face relations that happen one at a time.